Ever tried to change something on Wikipedia and hit a wall? You’re not alone. Thousands of editors propose edits to policies, guidelines, and workflows every year - but only a few succeed. The difference? They know how to use the Village Pump properly.

The Village Pump isn’t just a forum. It’s the heartbeat of Wikipedia’s community governance. It’s where editors debate whether to change how citations work, how to handle disruptive users, or whether a new policy should exist at all. But if you walk in like you’re posting on Reddit or Twitter, you’ll get ignored - or worse, backlash.

What the Village Pump Actually Does

The Village Pump (VP) is Wikipedia’s main discussion space for community-wide issues. It’s divided into sections: Technical, Policy, Misc, and others. Each section has a specific purpose. Policy proposals go in Village Pump (Policy). That’s where you’ll find debates about neutrality, sourcing rules, or edit restrictions.

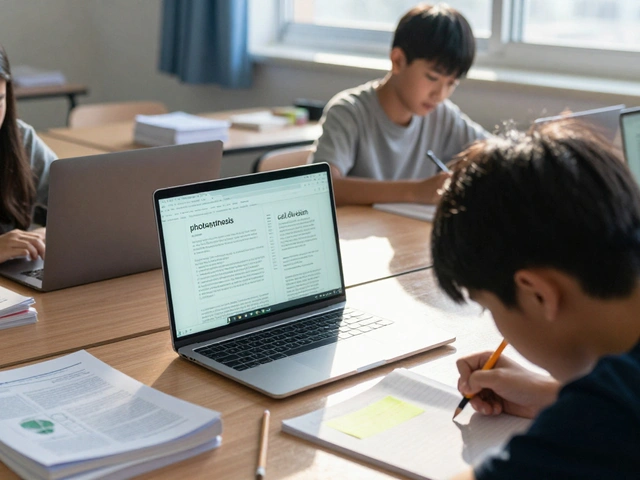

Unlike talk pages for individual articles, the Village Pump isn’t about fixing one page. It’s about changing how the whole site works. That means your proposal needs to speak to hundreds, not just a few editors. If you’re asking for a change that affects how 100,000 articles are edited, you can’t just drop a comment and leave. You need a plan.

Why Consensus Matters More Than Votes

Wikipedia doesn’t run on majority rule. You won’t find elections or polls deciding policy. Instead, it runs on consensus. That means you need enough editors to agree - not because they were outnumbered, but because they see your idea as fair, practical, and aligned with Wikipedia’s goals.

Consensus isn’t about getting 51% support. It’s about removing objections. If even one experienced editor says, “This will make it harder to verify facts,” and you don’t address it, your proposal stalls. You don’t need everyone to cheer. You just need no one to have a strong, reasoned objection.

Look at the 2023 proposal to update the No Original Research guideline. It didn’t pass because 120 people liked it. It passed because 37 editors raised concerns, and the proposer spent six weeks revising the draft to answer each one. That’s how Wikipedia works.

How to Start a Proposal the Right Way

Don’t jump straight to the Village Pump. Start small.

- Write a clear, one-paragraph summary of what you want to change. No jargon. No legalese.

- Explain why it matters. What problem does it solve? Give a real example: “Right now, editors remove citations to blogs because they’re ‘unreliable,’ but a blog written by a university professor citing peer-reviewed studies should count.”

- Propose a specific change. Don’t say “make sourcing better.” Say “add a clause allowing academic blogs as sources if they cite primary research and are authored by recognized experts.”

- Post it on a relevant talk page first - maybe the policy’s own talk page or a related noticeboard. Get feedback from 5-10 active editors.

- Only then, move to Village Pump (Policy).

This isn’t bureaucracy. It’s damage control. If you skip this, you’ll get 20 replies saying “I don’t understand this” or “This won’t work because…” - and you’ll have no idea how to fix it.

What Makes a Proposal Fail (And How to Avoid It)

Most proposals die for the same five reasons:

- Too vague. “Improve reliability” isn’t a proposal. “Require all medical claims to cite peer-reviewed journals, not textbooks” is.

- Too broad. Trying to rewrite the entire Neutral Point of View policy? No. Focusing on how to handle political bias in biographies? Maybe.

- No evidence. Saying “I’ve seen this happen a lot” isn’t enough. Link to three recent edit wars where this issue caused conflict.

- Ignoring existing rules. Did you check if this was already discussed in 2021? Search the policy’s talk page archive. If it was rejected before, explain why this time is different.

- Coming in hot. “This rule is stupid and needs to change NOW” gets you blocked from further discussion. Calm, factual, and open-ended language wins.

One editor in 2024 proposed changing how Wikipedia handles corporate PR edits. Their first draft said: “Companies are lying. We need to ban them.” The revised version said: “Recent studies show 68% of corporate Wikipedia pages contain promotional language not found in their official websites. I propose adding a warning template for pages with high edit frequency from corporate IPs.” The second version got 87 supportive comments. The first got 12 complaints and a warning.

How to Build Support Without Arguing

People don’t resist change because they’re stubborn. They resist because they’re overwhelmed. Wikipedia has over 100 active policies. Every editor is already juggling multiple rules. Your job isn’t to convince them you’re right. It’s to make your proposal feel like the obvious next step.

Do this:

- Use “we” instead of “you.” Say “We should clarify this” instead of “You’re doing it wrong.”

- Anticipate objections before they’re raised. If your proposal affects new editors, say: “This won’t make it harder for newcomers - here’s how we’ll update the help pages.”

- Offer to write the actual policy text. Most editors won’t. If you draft the exact wording, you remove a huge barrier.

- Tag active editors who’ve worked on similar topics. Don’t @ them like a tweet. Say: “Hi @UserX, you’ve helped shape the sourcing policy before. Would you mind reviewing this draft?”

Consensus grows slowly. It’s not a flash mob. It’s a slow tide. You need to show up week after week, answer every comment, and adjust your wording. That’s not tedious - it’s the only way.

What Happens After You Post

Once your proposal is live on Village Pump (Policy), expect 3-6 weeks of discussion. Don’t vanish. Check in every 2-3 days. Respond to every comment, even the negative ones. Silence looks like indifference.

Use this checklist:

- Did someone ask for an example? Add one.

- Did someone say it conflicts with another policy? Link to both and explain how they coexist.

- Did someone suggest a better wording? Say “Thanks, I’ve updated the draft to reflect that.”

- Did someone disappear after posting? Don’t assume they’re gone. Leave a polite follow-up: “Just checking in - did you have more thoughts on this?”

After 30-45 days, if there’s clear support and no major objections, someone (usually a longtime editor or administrator) will add a note: “Consensus reached.” That’s your green light.

What If Consensus Doesn’t Happen?

Most proposals don’t get consensus. That doesn’t mean you failed. It means you learned.

If your proposal stalls:

- Don’t repost it in a week. Wait 6 months. Come back with new data, a revised draft, or evidence that the problem got worse.

- Ask for feedback: “What would make this acceptable?”

- Try a smaller version. Instead of changing the whole policy, propose a trial on 10 articles.

- Join the Policy Committee. Many editors who successfully pass proposals started by helping others refine theirs.

One editor spent three years trying to get a rule added about citing social media. They failed four times. Each time, they listened. The fifth time, they didn’t ask for a rule. They asked for a pilot project. It ran for six months. Then they came back with data: “In 92% of cases, verified tweets improved accuracy.” That’s how it happened.

Final Tip: Be the Editor Who Makes It Easier

The best proposals don’t demand change. They make change feel inevitable. They don’t say, “We need this.” They say, “Here’s how we fix this without breaking anything else.”

Wikipedia’s rules aren’t written by experts in a room. They’re written by people like you - who showed up, listened, and kept showing up. The Village Pump isn’t a battleground. It’s a workshop. And the tools? They’re patience, clarity, and respect.

If you want to change Wikipedia, don’t shout. Build.

What is the Village Pump on Wikipedia?

The Village Pump is Wikipedia’s main community discussion forum, divided into sections like Policy, Technical, and Misc. It’s where editors propose changes to site-wide guidelines, debate policy updates, and resolve conflicts that affect multiple articles. It’s not for editing individual pages - it’s for shaping how Wikipedia works as a whole.

How is consensus different from a vote on Wikipedia?

Wikipedia doesn’t use votes. Consensus means enough editors agree because they see the proposal as fair, practical, and aligned with Wikipedia’s mission - not because they outnumber opponents. A proposal fails if even one editor raises a strong, reasoned objection that isn’t addressed. It’s about resolving concerns, not counting yes/no responses.

Can I just post my idea on the Village Pump and wait for support?

No. Jumping straight to the Village Pump without prior feedback usually leads to confusion or rejection. Start by posting your idea on the relevant policy’s talk page or a noticeboard. Get input from 5-10 active editors. Refine your proposal based on their feedback. Then bring it to the Village Pump with a clear draft and evidence of prior discussion.

What if no one responds to my proposal?

Silence doesn’t mean approval. It usually means your proposal isn’t clear, too broad, or hard to understand. Go back and simplify. Add a real example. Explain why it matters. Tag editors who’ve worked on similar topics. Sometimes, a polite follow-up after 7-10 days helps. If still no response, wait a few months and return with updated data or a revised version.

How long does a Village Pump proposal usually take to pass?

Most proposals take 30 to 60 days. Some take longer if there’s heavy debate or multiple revisions. A proposal that gets clear support and no major objections after 45 days may be marked as “consensus reached.” But if objections linger, it may stall for months - or require a trial run before final approval.

What should I do if my proposal is rejected?

Don’t repost immediately. Read the feedback carefully. Ask: “What would make this acceptable?” Try a smaller version - like a pilot project - or refine your wording based on objections. Many successful policies were proposed multiple times. The key isn’t persistence alone. It’s learning from each attempt and coming back with stronger evidence or clearer language.