When you see a photo in a Wikipedia news article-say, a protest in Hong Kong or a wildfire in California-it’s not just a random image pulled from Google. Every photo has a story behind it: who took it, when, where, and under what legal terms. Getting this right matters. A mislabeled photo can spread misinformation faster than a false headline. Wikipedia doesn’t just host facts-it hosts evidence. And photographic evidence has to be treated like forensic material.

Why Photos in News Articles Can’t Be Just Any Image

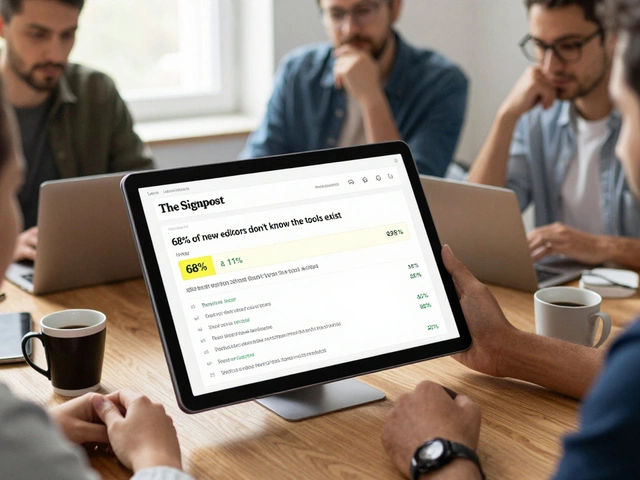

Wikipedia’s news-related articles often cover breaking events. In 2023, over 12 million images were uploaded to Wikimedia Commons. About 38% of those were used in articles tagged as news, politics, or current events. But not all of them belonged there. A 2022 audit by the Wikimedia Foundation found that 17% of images in news articles lacked clear licensing or source attribution. That’s more than one in six photos that could have been legally or ethically questionable.

Take the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Dozens of viral photos were repurposed in Wikipedia articles-some from verified journalists, others from social media accounts with no context. One photo, widely shared as showing a destroyed Ukrainian hospital, turned out to be from a 2016 conflict in Syria. It was still in use on Wikipedia for three weeks before being flagged and removed. That’s not just an error. It’s a failure of verification.

How Licensing Works on Wikipedia

Wikipedia requires all images to be freely licensed. That means the copyright holder must allow anyone to use, modify, and redistribute the image-even commercially-without paying. The most common licenses are:

- Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike (CC BY-SA): Used by most photos from journalists, NGOs, and public domain archives. Requires credit and sharing under the same terms.

- CC0 (Public Domain): The image has no copyright restrictions. Often used for government photos, like those from NASA or the U.S. National Archives.

- GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL): Older, less common now, but still found in legacy uploads.

Images under standard copyright-like those from AP, Reuters, or Getty-are not allowed unless explicitly released under a free license. Even if you paid for a photo or found it on a news site, that doesn’t make it legal to use on Wikipedia.

Some editors try to slip in photos labeled "fair use." But Wikipedia only permits fair use in extremely limited cases: when no free alternative exists, and the image is critical to understanding a topic. For example, a book cover or a logo might qualify. A photo of a protest? Almost never. Fair use images are heavily restricted and removed if challenged.

Verification: The Real Challenge

Licensing is the easy part. Verification is where most photos fail.

Editors use reverse image search tools like Google Images, TinEye, and Yandex to trace where a photo originated. They check metadata (EXIF data) for timestamps and GPS coordinates. They cross-reference with news reports, satellite imagery, and eyewitness accounts.

Consider the 2024 wildfire in Los Angeles. A photo circulated showing a burning mansion labeled as belonging to a celebrity. Reverse search showed it was from a 2018 fire in Northern California. The original caption had been edited out. The image was uploaded to Wikimedia Commons by a user claiming it was "recent." It took five editors, three days, and a Reddit thread to confirm the truth. The photo was deleted.

Another common trick: cropping. A photo of a crowd at a rally might be cropped to hide a counter-protester or a police vehicle. That changes the narrative. Editors look for unnatural edges, mismatched lighting, or inconsistent shadows. Tools like FotoForensics help spot manipulation.

Wikipedia’s policy is clear: if you can’t prove when, where, and by whom an image was taken-it doesn’t belong. And if the subject is a living person, especially in a sensitive context, consent matters. A photo of a child in a conflict zone? Even if it’s free to use, editors are instructed to avoid it unless it’s essential and the source can verify parental consent.

Who Checks This Stuff?

Wikipedia doesn’t have a team of fact-checkers sitting in an office. Verification is done by volunteers-sometimes hundreds of them. The Wikimedia Commons community has a dedicated group called the Image Review Team. They handle flagged images daily. You don’t need to be a journalist to help. All you need is a Google account, patience, and access to reverse image tools.

There’s also the Wikipedia:Reliable sources guideline, which applies to images as much as text. If a photo is sourced from a blog with no credibility, or from a Twitter account with 12 followers, it’s rejected. The gold standard is photos from:

- News agencies (AP, Reuters, AFP)

- Government archives (NASA, NOAA, EU institutions)

- Academic institutions with open photo libraries

- Photographers who explicitly release work under CC BY-SA

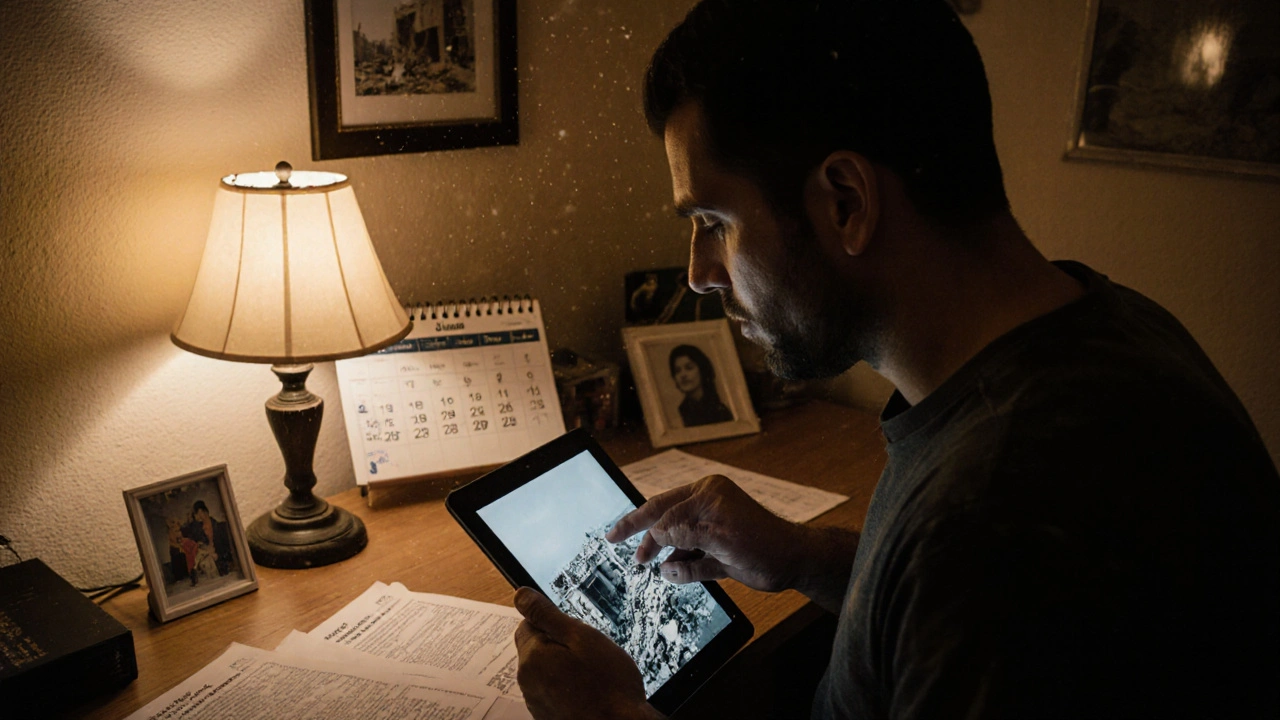

Some photographers upload their own work directly to Wikimedia Commons. One photojournalist from Syria, who lost his home in 2016, has uploaded over 800 images of the war-all under CC BY-SA. He includes detailed captions, timestamps, and locations. His work is now cited in dozens of articles about the Syrian conflict. That’s the model.

What Happens When a Photo Is Wrong?

When a false or improperly licensed photo stays on Wikipedia, the consequences ripple. Other sites copy Wikipedia. Academic papers cite it. Media outlets use it as a "source." In 2021, a mislabeled photo of a Russian tank was used in a BBC article, which then appeared in a German newspaper. The error was traced back to a Wikipedia article that had been edited by a bot that auto-uploaded images from a Flickr account with no license info.

Wikipedia has a formal process for cleanup. Editors tag problematic images with templates like {{Wrong license}} or {{Possible copyright violation}}. Once tagged, the image is reviewed within 72 hours. If confirmed as invalid, it’s deleted. The article is updated. And the editor who uploaded it gets a gentle reminder-sometimes with a link to the licensing guide.

But the system isn’t perfect. Volunteer burnout is real. Some editors are overworked. Others lack training. That’s why Wikipedia has started partnering with journalism schools. Students at Columbia University and the University of Missouri now take courses on verifying Wikimedia images. They’re not just learning ethics-they’re helping fix real articles.

What You Can Do

You don’t need to be an editor to help. If you see a photo in a Wikipedia news article that looks off:

- Check the image description page. Is there a clear license? Is the source named?

- Do a reverse image search. Does it show up elsewhere with different dates or locations?

- Look for inconsistencies: Is the weather right for the location? Are the cars or clothing styles outdated?

- If something’s wrong, click "Edit" on the image page and add a note. Or flag it using the template system.

Even small actions matter. In 2024, a high school student in Wisconsin noticed a photo in a Wikipedia article about a U.S. Senate vote that was mislabeled as being from 2023. It was actually from 2019. She filed a report. The image was removed. The article was corrected. That’s how Wikipedia works-not because someone in charge told it to, but because people care enough to check.

Where to Find Legally Safe Photos

If you’re writing or editing a Wikipedia article and need a photo, here are trusted sources:

- Wikimedia Commons: The central repository. Filter by license and date.

- U.S. National Archives: Millions of public domain images from U.S. government agencies.

- European Photobank: Images from EU institutions, all CC0.

- Reuters and AP Open Access: Some news agencies now offer select images under CC BY-SA for non-commercial use.

- Flickr Creative Commons: Search with the filter "Creative Commons licenses" and verify each photo’s specific terms.

Avoid: Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, personal blogs, or any site that doesn’t clearly state licensing. Even if the photo looks perfect, if you can’t prove its origin and rights, it’s too risky.

Can I use a photo from a news website on Wikipedia?

Only if the news website explicitly states the image is under a free license like CC BY-SA or CC0. Most news sites hold copyright and do not allow reuse. Even if you link to the original, that doesn’t make it legal on Wikipedia. Always check the image’s license page.

What if I took the photo myself?

You can upload it to Wikimedia Commons if you own the copyright. You must choose a free license (CC BY-SA 4.0 is recommended). Include the date, location, and subject. If the photo includes identifiable people, especially in sensitive situations, you should get their consent before uploading.

Why can’t Wikipedia use fair use photos like TV shows do?

Wikipedia is a global, non-profit encyclopedia. Fair use is a U.S.-specific legal exception that doesn’t apply everywhere. To serve readers worldwide, Wikipedia only allows images that are legally free to use in every country. Fair use images are too risky and too limited to be reliable.

How long does it take to verify a photo on Wikipedia?

It varies. Simple cases with clear metadata take minutes. Complex cases-like disputed war photos-can take weeks. The system relies on volunteers, so urgency depends on how many people notice the issue. Tagging images helps speed things up.

Are there tools to help verify photos?

Yes. Google Images reverse search, TinEye, and Yandex Images are free tools used daily. Advanced users use ExifTool to check metadata, and FotoForensics to detect editing. Wikipedia also has a built-in image review dashboard that flags suspicious uploads.

Photographic evidence in Wikipedia isn’t just decoration. It’s part of the record. A single image can confirm a war crime, document a climate disaster, or expose a political lie. That’s why every upload must be treated like a court exhibit-properly sourced, legally cleared, and thoroughly verified. The system isn’t flawless, but it’s the most transparent, community-driven fact-checking network in the world. And it only works because people keep checking.