There are over 2,000 languages spoken across Africa. Yet until recently, fewer than 50 of them had a Wikipedia page. That’s not just a gap in technology-it’s a gap in identity, history, and knowledge. Today, African language Wikipedias are growing fast, but they’re still fighting for space, recognition, and contributors. This isn’t about translating English articles. It’s about building knowledge from the ground up, in languages that millions speak every day but rarely see in digital form.

Why African Language Wikipedias Matter

Imagine trying to explain your family’s traditional healing practices to a child, but the only online resources are in English, French, or Portuguese. You can’t find the right words. The concepts don’t translate. That’s the reality for most African communities. When knowledge only exists in colonial languages, it becomes disconnected from daily life. African language Wikipedias change that. They let people write about local crops, ancestral customs, regional history, and modern innovations in the language they think in.

Swahili Wikipedia, launched in 2003, now has over 100,000 articles. Yoruba Wikipedia, started in 2005, has more than 35,000. Zulu, Hausa, and Amharic each have over 20,000. These aren’t just numbers-they’re living archives. A farmer in Kenya can look up drought-resistant maize varieties in Swahili. A student in Nigeria can read about pre-colonial trade routes in Yoruba. A grandmother in Ethiopia can teach her grandchild about traditional embroidery patterns in Amharic. That’s the power of having knowledge in your mother tongue.

How African Language Wikipedias Are Built

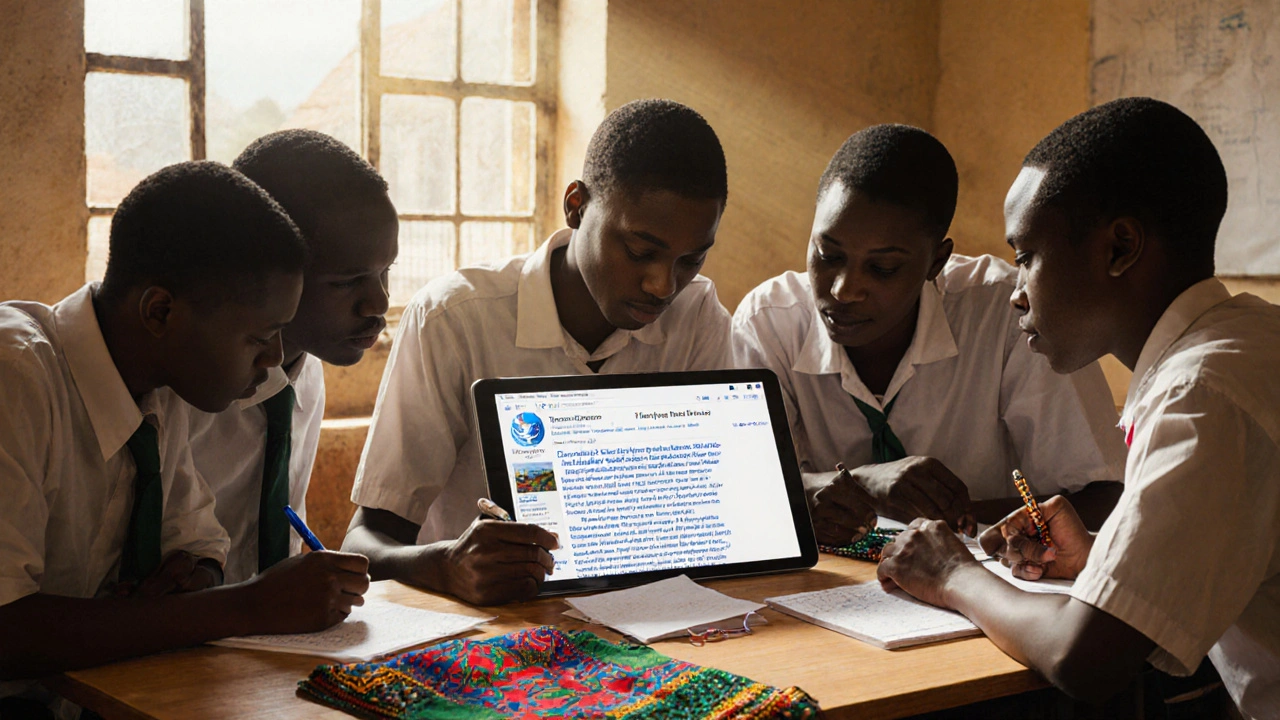

Unlike English Wikipedia, which grew from millions of volunteers worldwide, African language Wikipedias are built by small, passionate groups. Many are students, teachers, librarians, or community activists. They don’t have big budgets or corporate backing. They use smartphones, public Wi-Fi, and free time after school or work.

The process is hands-on. Contributors don’t just copy-paste from English. They research local sources-oral histories, community meetings, printed books from small publishers, even handwritten notes passed down through generations. One Zulu contributor spent months interviewing elders in KwaZulu-Natal to document traditional herbal remedies. Another group in Mali transcribed radio broadcasts about local governance into written articles. These aren’t perfect entries. Some have typos. Some lack citations. But they’re real. And they’re growing.

Tools like the Content Translation tool help, but they’re not enough. Many African languages don’t have digital keyboards, spell-checkers, or grammar tools built into operating systems. Contributors often build their own templates, create glossaries, and teach each other how to format articles. It’s grassroots tech development at its most human.

Challenges: Lack of Support, Lack of Visibility

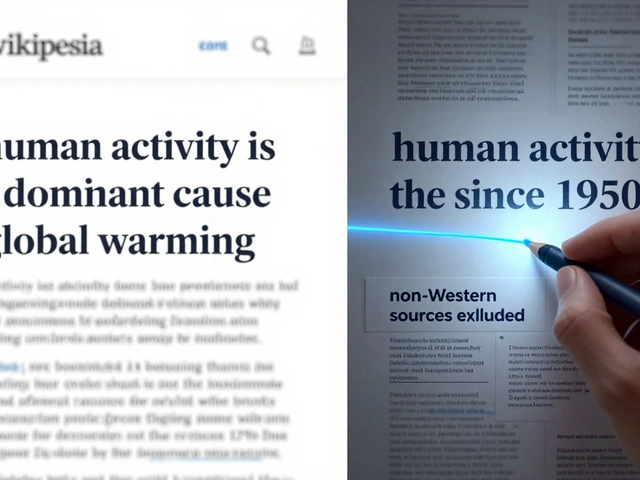

Despite their value, African language Wikipedias get almost no attention from global institutions. The Wikimedia Foundation spends most of its funding on English, German, and French editions. African language projects rarely get grants, training, or technical support. Many editors say they’ve emailed Wikipedia staff dozens of times asking for font support, mobile app improvements, or help with image uploads-and got no reply.

There’s also a perception problem. Many people assume African languages can’t handle complex topics. That’s false. Swahili has words for quantum physics, artificial intelligence, and constitutional law. The issue isn’t the language-it’s the lack of investment in making those words visible online.

Another barrier is access. In rural areas, internet is slow or expensive. A single article with five images can cost more than a day’s wages in data. Many contributors work offline, writing in notebooks or on phones with no connection, then upload when they find a free hotspot. Some use USB drives to share articles between villages.

Success Stories That Changed the Game

Not all stories are about struggle. Some African language Wikipedias have become models for change.

In Ghana, the Twi Wikipedia project partnered with local radio stations. Each week, a host reads a new Twi Wikipedia article on air. Listeners call in with corrections or additions. Now, the Twi Wikipedia has over 18,000 articles-and it’s the most edited African language Wikipedia in West Africa.

In South Africa, the isiXhosa Wikipedia became part of a national curriculum pilot. Schools now teach students how to edit Wikipedia as part of their computer literacy class. Students write about local landmarks, family trees, and community events. Teachers report that kids who used to hate writing now spend hours researching and editing.

One of the most powerful examples is the Wolof Wikipedia in Senegal. A group of university students started it in 2010 with just 12 articles. Today, it has over 40,000. They created a mobile app that lets users read articles without internet. They trained over 500 high school students to contribute. And they got the Senegalese Ministry of Education to recognize Wikipedia edits as part of student assessment.

What’s Missing: More Than Just Articles

There’s still a huge gap between what exists and what’s needed. African language Wikipedias lack:

- High-quality images of local landmarks, plants, and cultural objects

- Audio pronunciations for words and names

- Structured data like infoboxes for diseases, species, or historical figures

- Integration with local libraries and archives

For example, there’s no Wikipedia article in Lingala that describes the medicinal properties of nguya (a plant used in Central Africa for fever), complete with photos and scientific names. There’s no article in Kinyarwanda that lists all the traditional weaving patterns from Rwanda’s provinces. These gaps aren’t because people don’t know-they’re because no one has had the time, tools, or support to write them.

How You Can Help

You don’t need to speak an African language to help. Here’s how:

- Upload free images of African plants, architecture, or cultural items to Wikimedia Commons. Label them with local names.

- Translate simple articles from English into African languages using Wikipedia’s translation tool. Start with basic topics: weather, health, food.

- Donate to local Wikimedia chapters in Nigeria, Kenya, or Senegal. They use funds for data bundles, training workshops, and printing guides.

- Encourage schools to teach Wikipedia editing in African languages. Even one class can spark a movement.

The biggest thing you can do? Stop assuming African languages are “not ready” for digital knowledge. They’re already there. They just need space to grow.

What’s Next for African Language Wikipedias

The next five years will decide if these projects survive as niche efforts-or become pillars of Africa’s digital future. More universities are starting language technology labs. Governments in Ethiopia, Ghana, and Senegal are drafting policies to support digital content in local languages. AI tools are beginning to support African languages, though poorly. The real breakthrough will come when African language Wikipedias are no longer seen as “projects for the Global South,” but as essential parts of the global knowledge ecosystem.

Imagine a world where a child in Lagos, a farmer in Addis Ababa, and a student in Maputo can all find answers to their questions in the language they grew up with. That’s not a dream. It’s already happening-one article, one edit, one voice at a time.

Why don’t more African languages have Wikipedia pages?

Many African languages lack digital infrastructure-keyboards, spell-checkers, and fonts. There’s also limited funding and technical support from global organizations. Most editors are volunteers with little time or resources. But the biggest barrier is perception: people assume these languages can’t handle complex topics, which isn’t true. The languages are ready. The systems aren’t.

Which African language Wikipedia has the most articles?

Swahili Wikipedia leads with over 100,000 articles, followed by Yoruba with more than 35,000. Zulu, Hausa, and Amharic each have over 20,000. These numbers reflect decades of community effort, not just population size. Swahili’s lead comes from its use as a regional lingua franca across East Africa and strong university involvement.

Can I contribute even if I don’t speak an African language?

Yes. You can upload free-to-use images of African plants, buildings, or cultural items to Wikimedia Commons and tag them with local names. You can also translate simple English articles into African languages using Wikipedia’s built-in tool. Even helping spread the word-telling teachers, librarians, or community groups about these projects-makes a difference.

Are African language Wikipedias reliable?

They’re as reliable as any Wikipedia: community-edited and constantly improving. Many articles are written by locals with deep knowledge-elders, teachers, healers, historians-who have never seen an English Wikipedia page. These aren’t translations; they’re original knowledge. While some articles need citations, the best ones are backed by oral histories, field research, and local publications. They often contain information you won’t find anywhere else online.

How do I find African language Wikipedias?

Go to wikipedia.org and click on any language in the sidebar. Scroll down to find African languages like Kiswahili, Yoruba, Zulu, or Amharic. You can also search for “Wikipedia in [language name]” in your browser. Most are fully functional and open to edits from anyone.