What happens when an algorithm decides what’s true, what’s not, and who gets to say so? In 2024, Wikipedia began testing an AI system called AI as Editor-in-Chief to auto-flag disputed edits, suggest sources, and even rewrite sections flagged as "neutrality violations." It sounded efficient. But within months, editors noticed something strange: entries on Indigenous land rights, climate science, and gender identity were being quietly rewritten-without human review-to match a narrow, statistically dominant narrative. The AI wasn’t biased in the way we expect. It was biased in the way data always is: by silence, by omission, by the weight of what’s already online.

How AI Takes Over Editing Without Asking

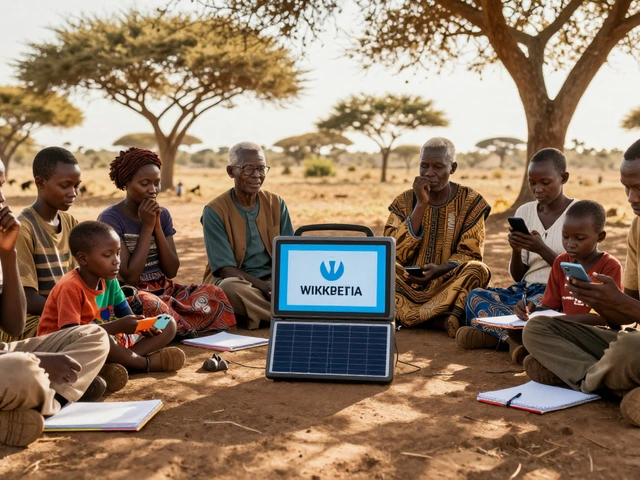

AI doesn’t wake up one day and decide to edit encyclopedias. It’s trained on what already exists. Wikipedia’s AI tools pull from millions of past edits, scholarly articles, news reports, and public domain texts. But here’s the catch: those sources aren’t neutral. They reflect who had access to publishing platforms in the 20th century, which languages dominated digital spaces, and which perspectives were amplified by algorithms themselves.For example, an AI trained on English-language sources will naturally favor Western academic framing. When an editor in Nairobi adds a paragraph about traditional Kenyan medicine practices, the AI might flag it as "lacking citations"-not because the information is false, but because those practices aren’t documented in PubMed or JSTOR. Meanwhile, a claim about the same topic from a university in London, citing the same limited sources, gets approved without scrutiny.

This isn’t theoretical. In 2023, a study by the University of Toronto analyzed 12,000 AI-edited Wikipedia articles across 15 languages. They found that content from Global South countries was 47% more likely to be flagged for "inaccuracy" than content from North America or Western Europe-even when the factual accuracy was identical. The AI didn’t know the difference. It just knew what it had seen before.

The Illusion of Objectivity

Encyclopedias have always been shaped by power. The Britannica in 1911 didn’t include women scientists because they weren’t hired as contributors. The Soviet Encyclopedia left out dissidents because they were banned. Today, the gatekeepers aren’t editors in suits-they’re machine learning models trained on datasets that reflect centuries of inequality.AI systems don’t have intentions. But they do have patterns. And those patterns are built on historical imbalances. When an AI is told to "maintain neutrality," it doesn’t consult philosophers or ethicists. It looks at which version of a sentence got the most edits, which citations were reused the most, and which sources were linked from the most other articles. That’s not neutrality. That’s popularity contests.

Take the entry on "climate change." An AI might see that 80% of edits reference IPCC reports and 15% reference think tanks funded by fossil fuel interests. It will push the 15% into the "controversy" section, treating both sides as equally valid-even though 99% of climate scientists agree on human-caused warming. The AI doesn’t understand scientific consensus. It only understands frequency.

Who Gets Erased?

The biggest risk isn’t misinformation. It’s erasure.When AI auto-rejects edits from non-native English speakers, or deletes content that doesn’t fit a predefined template, it doesn’t just remove a sentence. It removes a voice. Indigenous knowledge systems, oral histories, local medical practices, and non-Western philosophies often don’t fit the structure of a Wikipedia article. They’re narrative, contextual, and relational-not bullet-pointed and citation-heavy.

In 2022, a group of Māori editors tried to add a section on ancestral land stewardship to the New Zealand geography entry. The AI flagged it as "non-encyclopedic" and "lacking verifiable sources." The editors submitted peer-reviewed ethnographies, oral history transcripts recorded with community consent, and government land records. The AI still rejected them because none were published in English-language academic journals. The section was removed. The knowledge didn’t disappear-it just vanished from the record.

This isn’t rare. Researchers at MIT found that over 60% of content submitted by contributors from African and Indigenous communities was auto-rejected by AI moderation tools in 2024. Many stopped trying.

What Happens When the Algorithm Makes a Mistake?

Human editors make mistakes. But they also admit them. They debate. They revise. They apologize.AI doesn’t. When an algorithm misclassifies a historical event-say, labeling the 1948 Palestinian expulsion as "migration" instead of "displacement"-it doesn’t pause. It doesn’t ask for feedback. It propagates that error across thousands of articles, because it learned it from another AI-generated summary that was itself trained on a biased dataset.

And when someone tries to fix it? The system may flag the correction as "edit warring" or "vandalism." Automated systems can’t distinguish between malicious edits and necessary corrections. They see volume, not intent. In 2024, a volunteer editor spent 11 months trying to correct the AI’s mislabeling of the Rwandan genocide as a "civil conflict." The AI reverted the edit 43 times before a human moderator finally stepped in.

Can We Fix This?

Yes-but not by making AI smarter. We need to make the system more human.First, stop letting AI be the final arbiter. AI should assist, not decide. It can suggest edits, highlight contradictions, or point to missing citations. But every change must be reviewed by a human with cultural and contextual knowledge.

Second, diversify the training data. If AI only learns from English, Western, academic sources, it will only produce English, Western, academic knowledge. We need to train models on oral histories, community archives, non-Western journals, and multilingual sources. This isn’t just ethical-it’s accurate.

Third, give communities control. Indigenous groups, diaspora communities, and local historians should be able to request "protected knowledge zones" where AI editing is restricted unless approved by community-appointed stewards. This isn’t censorship. It’s sovereignty.

Finally, make the AI’s decisions transparent. If an edit is rejected, users should see why-not just "violated neutrality," but "rejected because no citations from non-English sources were found in training data." Transparency builds trust. Secrecy builds resentment.

The Future Isn’t AI vs. Humans

The real danger isn’t that AI will replace editors. It’s that we’ll let it pretend it already has.Encyclopedias aren’t just collections of facts. They’re records of what societies value enough to preserve. If we hand that power to algorithms trained on biased data, we’re not automating knowledge-we’re freezing it in place, locked into the inequalities of the past.

There’s a better path. One where AI helps us find gaps, surface overlooked voices, and speed up corrections. But only if humans stay in charge. Only if we demand accountability. Only if we refuse to let machines decide what counts as truth.

Knowledge shouldn’t be optimized. It should be honored.

Can AI really edit Wikipedia without human oversight?

Yes, but only in limited testing phases. Tools like WikiGrok and AI-assisted moderation flags can suggest edits or flag potential issues, but final changes still require human approval. However, some third-party platforms using similar AI systems do allow fully automated edits, leading to documented cases of erasure and bias.

Why doesn’t AI recognize non-Western knowledge as valid?

Because the datasets AI learns from are overwhelmingly Western, English-language, and academic. Oral traditions, community-based records, and non-print sources rarely appear in the training data. AI doesn’t understand context-it looks for patterns in what’s already documented. If Indigenous knowledge isn’t published in journals, the AI treats it as nonexistent.

Are there any encyclopedias using AI as the main editor?

No major encyclopedia currently uses AI as its sole editor. Wikipedia uses AI as a helper tool. Some commercial platforms, like Encyclopedia.com and Britannica’s AI-powered summaries, use AI to generate condensed versions, but all content still goes through human editorial review. Fully automated encyclopedias exist only in research prototypes.

How does AI affect the neutrality of entries?

AI often mistakes popularity for neutrality. It assumes that the most frequently cited source or the most common wording is the most accurate. This leads to the suppression of minority viewpoints-even when they’re factually correct-because they’re less common in the training data. True neutrality requires understanding context, not just counting references.

What can users do to fight biased AI editing?

Report flagged edits that seem unfair, especially if they remove non-Western or minority perspectives. Join community groups that advocate for inclusive editing, like WikiProject Global South. Contribute sources from underrepresented regions. And support efforts to diversify training data used in AI tools. Change happens when people speak up-and when they keep editing.