Wikipedia isn’t just a website. It’s a living, breathing system run by volunteers who argue over whether a celebrity’s tattoo counts as notable, if a local politician’s tax record belongs on their page, or whether a conspiracy theory should be mentioned at all-even to debunk it. These aren’t minor tweaks. They’re high-stakes policy battles that decide what knowledge stays, what gets erased, and who gets to decide.

The Neutral Point of View Fight

The cornerstone of Wikipedia’s identity is the Neutral Point of View (NPOV) policy. It sounds simple: present facts without bias. But in practice, it’s a minefield. Editors from different countries, cultures, and ideologies interpret neutrality differently. In 2023, a dispute over how to describe the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests led to over 2,000 edits in a single week. One group insisted on using "political unrest," another demanded "government crackdown," and a third argued the event shouldn’t be mentioned at all. The final version, after months of debate, used "government response to pro-democracy demonstrations," a compromise that satisfied no one but met the policy’s letter.

NPOV isn’t just about politics. It’s applied to science, religion, gender, and even food. In 2024, editors fought for weeks over whether to call plant-based meat "imitation meat." Some said it was misleading; others argued it was accurate. The policy doesn’t say what to call things-it says to reflect reliable sources. So the solution? List how major publications describe it: "plant-based meat" (The New York Times), "fake meat" (The Daily Mail), "meat alternative" (BBC). No single term wins. The page just lists them all.

Notability and the Gatekeepers

Notability is Wikipedia’s invisible filter. If you’re not mentioned in enough reliable sources, you don’t get a page. That sounds fair-until you realize who gets left out. In 2022, a group of editors deleted the page of a Nigerian environmental activist who had led successful protests against oil pollution. Why? Because she wasn’t covered by Western media. The page was restored after local journalists submitted articles from Nigerian newspapers. But the incident exposed a deep bias: Wikipedia’s notability standards still favor Anglo-American sources.

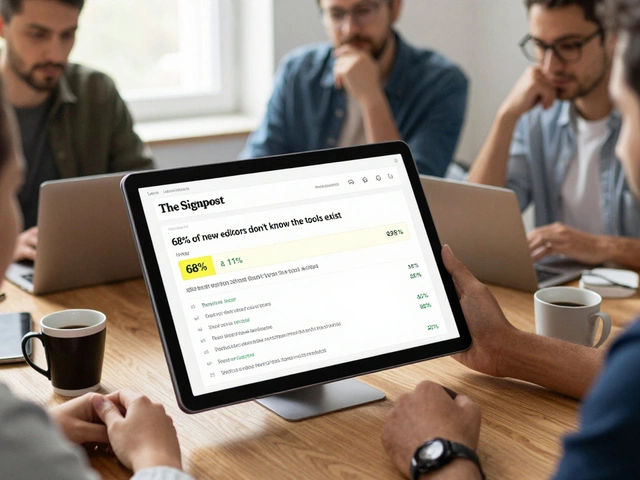

That’s why the "Notability (people)" guideline is under constant review. A 2024 proposal suggested adding criteria for activists, indigenous leaders, and grassroots organizers based on local media coverage. The proposal passed in a vote of 68% to 32%, but enforcement is uneven. Editors in the U.S. and Europe still delete pages for lack of coverage in The Guardian or The New York Times. Editors in India, Brazil, and Kenya push back, citing regional outlets like The Hindu, Folha de S.Paulo, or Daily Trust. The result? A patchwork of pages-some richly detailed, others missing entirely-depending on where you live.

Conflict of Interest and Paid Editing

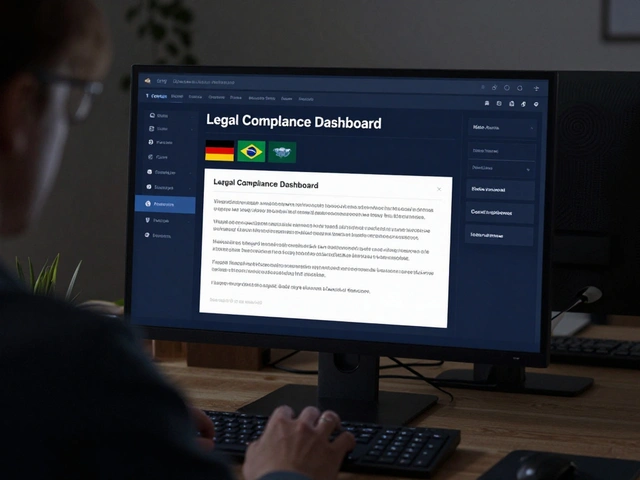

Wikipedia bans paid editing. But it’s impossible to police. PR firms, lobbyists, and corporations hire people to quietly improve their pages. In 2023, a Wikipedia administrator flagged a pattern: 17 edits to a pharmaceutical company’s page, all made from the same IP address linked to a marketing agency in London. The edits softened language about side effects and added quotes from a study funded by the company. The page was locked, the edits reverted, and the user banned. But how many others slipped through?

Wikipedia’s Conflict of Interest (COI) policy says you should disclose if you’re being paid. But most paid editors don’t. A 2025 study by the University of Toronto found that 42% of corporate Wikipedia pages showed signs of paid editing-yet only 3% had any disclosure. The platform relies on volunteers to spot these edits. That’s like asking neighbors to police a city without cameras or police. The system works… until it doesn’t. When a major brand’s page gets flagged for misinformation, the damage is already done. Millions have already read it.

Blocking and the Power to Erase

Wikipedia’s administrators can block users-sometimes for years. They can delete entire pages. They can lock articles so no one can edit them. That power is supposed to be used sparingly. But in practice, it’s a tool for control. In 2024, a longtime editor from the Philippines was blocked for six months after repeatedly challenging the inclusion of a mythological figure in a history article. The admin said the edits were "disruptive." The editor said they were citing local folklore. The block stood.

These blocks aren’t always about policy. They’re about influence. A 2023 analysis by the Wikimedia Foundation found that 70% of long-term blocks were issued by just 5% of administrators. And those admins are mostly from North America and Western Europe. There are over 1,000 active administrators worldwide-but only 12% are from Africa, Latin America, or Southeast Asia. That means decisions about what counts as "disruption," "vandalism," or "bias" are often made by people who don’t live the cultures they’re judging.

The Rise of AI and the Collapse of Trust

AI-generated content is flooding Wikipedia. In 2025, automated tools created over 1.2 million edits. Most are harmless: fixing typos, updating population numbers, adding citations. But some are dangerous. A bot edited the page for "climate change" to include a false claim that "78% of scientists disagree with human-caused warming." The source? A blog post from a think tank with no peer review. It stayed live for 11 days before a volunteer caught it.

Wikipedia’s policy says all content must come from reliable, published sources. But AI can fabricate fake sources that look real. It can mimic the tone of The Lancet or Nature. And it’s getting better. A 2025 test by MIT found that 38% of AI-generated citations on Wikipedia were indistinguishable from real ones to human editors. The platform has no way to detect them. Volunteers are overwhelmed. The result? A slow erosion of trust. A 2025 Pew Research survey found that only 48% of U.S. adults now trust Wikipedia as a primary source-down from 67% in 2020.

Who Gets to Decide?

Wikipedia’s policies are written by volunteers. But who are those volunteers? Most are men, mostly between 25 and 45, mostly from the U.S., Europe, or Australia. Less than 15% are women. Fewer than 5% are from Africa. The governance structure-where policies are voted on-is open to anyone with an account. But in practice, only a few hundred people show up for votes. The rest of the world watches, edits quietly, or leaves.

That’s why the most heated debates now aren’t about facts. They’re about power. Should a policy written in English by editors in California apply to a page about a rural Indonesian tradition? Should a German editor’s interpretation of "reliable source" override a local journalist’s reporting? These aren’t technical questions. They’re ethical ones.

Wikipedia still says it’s open to everyone. And technically, it is. But the system rewards persistence, technical skill, and cultural fluency in Western academic norms. That’s not neutrality. That’s exclusion dressed up as policy.

What’s Next?

Wikipedia is at a turning point. It can double down on its old rules-strict, rigid, and dominated by a small group. Or it can adapt. Some are pushing for regional policy councils, where editors from Africa, Asia, and Latin America draft guidelines for their own contexts. Others want AI detection tools built into the editing interface. A few are calling for mandatory diversity quotas among administrators.

There’s no easy fix. But one thing is clear: if Wikipedia wants to stay relevant, it can’t keep pretending neutrality means silence. It has to choose whose voices count-and that’s the most controversial policy of all.

Why does Wikipedia have so many policy debates?

Wikipedia has no central authority. Every rule is created and enforced by volunteers, and those volunteers often disagree on what’s fair, accurate, or neutral. With over 60 million articles and millions of editors, even small differences in interpretation lead to big conflicts. Policies like NPOV and notability are meant to bring order-but they also become battlegrounds for cultural, political, and ideological values.

Can anyone edit Wikipedia’s policies?

Yes, technically. Anyone with a registered account can propose changes to policy pages. But real influence comes from participation. Most policy changes are debated on talk pages, then voted on by active editors. The people who show up regularly-often the same few hundred-end up shaping the rules. That’s why global representation matters: if most voters are from North America or Europe, policies will reflect their priorities, not the world’s.

Are Wikipedia’s administrators biased?

Studies show that most administrators are from Western countries, are male, and have been editing for years. That doesn’t mean they’re intentionally biased, but their cultural background influences how they interpret policies. A block for "disruptive editing" might be seen as necessary by one admin and as censorship by another. The system relies on consensus, but consensus is easier to reach among people who think similarly.

How does AI affect Wikipedia’s reliability?

AI can generate convincing but false citations and edit summaries that look legitimate. While most AI edits are harmless, some introduce misinformation that slips past human reviewers. Wikipedia has no built-in tool to detect AI-generated content, so volunteers must catch it manually. With over a million AI edits in 2025, the system is stretched thin. Trust in Wikipedia has dropped as a result.

Why aren’t more women and people from the Global South editing Wikipedia?

Many factors: cultural norms, language barriers, lack of access to technology, and a community culture that can feel unwelcoming. The technical complexity of editing, the aggressive tone of some debates, and the dominance of Western perspectives make it harder for newcomers-especially women and non-Western editors-to feel like they belong. Efforts to recruit them have had limited success because the system hasn’t changed to accommodate different ways of knowing.