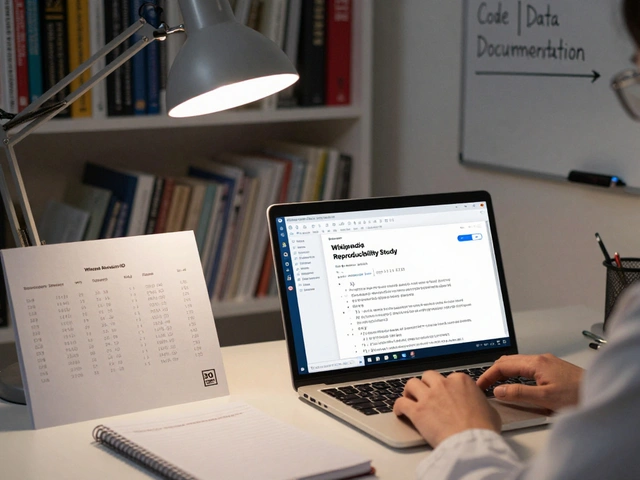

When you need to know something fast, where do you go? For most people, it’s still Wikipedia. But over the last two years, something’s changed. AI-powered encyclopedias-tools like Google’s AI Overviews, Perplexity, and even new platforms like Consensus and Elicit-are popping up everywhere. They promise faster answers, summaries, and even sources. So what do real people think? Surveys from 2024 and early 2025 tell a clear story: trust in Wikipedia isn’t fading. It’s being tested.

Wikipedia Still Wins on Trust

A 2024 Pew Research study surveyed over 10,000 U.S. adults on where they get factual information. When asked which source they trusted most for general knowledge, 68% picked Wikipedia. Only 19% said they trusted AI-generated summaries. That gap didn’t shrink in 2025, even after major AI tools got upgrades. Why? Because people know Wikipedia’s rules. They’ve seen the edit history. They’ve watched debates over whether a fact belongs there. They understand it’s written by volunteers, not algorithms.

Compare that to AI encyclopedias. In the same survey, 42% of respondents admitted they’d been given a confidently stated answer by an AI that turned out to be wrong. One woman in Ohio told researchers she asked an AI assistant, "When was the first moon landing?" It replied, "July 20, 1969, with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin." Then it added, "They brought back moon rocks that are now displayed at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center." The rocks aren’t there. They’re in Houston. The AI didn’t just get one detail wrong-it stitched together plausible-sounding lies.

People Don’t Trust AI’s Sources

AI encyclopedias brag about citing sources. But here’s the catch: they often cite fake or misleading ones. A 2025 University of Michigan study tested 500 questions across three major AI tools. In 37% of cases, the cited sources didn’t exist. In another 22%, the sources were real but didn’t say what the AI claimed. One AI tool cited a "Harvard Journal of Medical Ethics" article that didn’t exist. Another quoted a "National Science Foundation report" that was just a blog post.

Wikipedia doesn’t have perfect citations, but it has a system. Every claim with a star next to it means someone checked the source. If you click it, you go to the real article, book, or study. If you’re skeptical, you can see who edited it, when, and why. AI tools hide their sources behind a single link. You can’t see the chain of reasoning. You just get a summary-and no way to verify it.

Speed vs. Accuracy: The Trade-Off

AI tools are fast. Really fast. Ask "What’s the capital of Mongolia?" and you get the answer in under a second. Wikipedia takes maybe three. That’s not a big deal for most people. But when the stakes are higher, speed becomes a liability.

Survey data from the Knight Foundation shows that 73% of college students now use AI tools for quick research. But 61% of them say they still double-check the answer on Wikipedia. Why? Because they’ve been burned. One student in Texas wrote a paper using an AI-generated summary that claimed the 2020 U.S. election was "certified by all 50 states with no disputes." The AI pulled that from a fringe blog. Wikipedia had a detailed, sourced breakdown of the certification process, including contested recounts in Georgia and Arizona.

People don’t mind using AI for brainstorming or quick definitions. But when they need to be sure, they go back to Wikipedia. It’s not about nostalgia. It’s about control.

Who Writes the Answers?

Wikipedia’s strength isn’t just its editing process-it’s its people. Over 100,000 active editors worldwide contribute daily. Many are experts: professors, librarians, doctors, engineers. They don’t get paid. They do it because they care. You can read their talk pages. You can see their reasoning.

AI encyclopedias? They’re trained on data-books, websites, articles-but they don’t know who wrote them. They don’t care. They just predict what words come next. That’s why they hallucinate. That’s why they get dates wrong. That’s why they invent sources. They’re not trying to be accurate. They’re trying to sound accurate.

Surveys show people notice this difference. When asked, "Do you believe the person or system giving you this answer has a reason to be truthful?"-76% said yes for Wikipedia. Only 31% said yes for AI tools. The difference isn’t technical. It’s psychological. People trust humans who show their work. They don’t trust machines that hide theirs.

Wikipedia Isn’t Perfect

Let’s be honest: Wikipedia has problems. It’s slow to update on breaking news. It can be biased. Some topics are covered in depth; others are thin. There are edit wars. Vandalism happens. But it has checks. It has transparency. It has a community that argues over every comma.

AI encyclopedias don’t have any of that. They’re black boxes. You can’t argue with them. You can’t fix them. You can’t even see how they got the answer. If you spot an error, you can’t edit it. You can only hope the company fixes it-or switch to another tool.

That’s why Wikipedia still dominates in countries with high media literacy: Canada, Germany, Japan, Australia. In places where people are taught to question sources, Wikipedia wins. In places where people just want quick answers, AI tools gain ground. But even there, trust is fragile.

What the Future Holds

AI tools aren’t going away. They’re getting better. Some are starting to integrate Wikipedia data directly. Google’s AI Overviews now pull from Wikipedia pages in 80% of cases. That’s not a threat-it’s validation. AI companies are using Wikipedia as their source because they know people trust it.

Wikipedia’s future might not be as the sole answer. But it’s becoming the foundation. The most reliable AI encyclopedias will be the ones that link to Wikipedia, not replace it. The ones that say, "Here’s what Wikipedia says-and here’s how I got there."

For now, if you want to know something for sure, you still go to Wikipedia. Not because it’s perfect. But because it’s the only place where you can see how the answer was built.