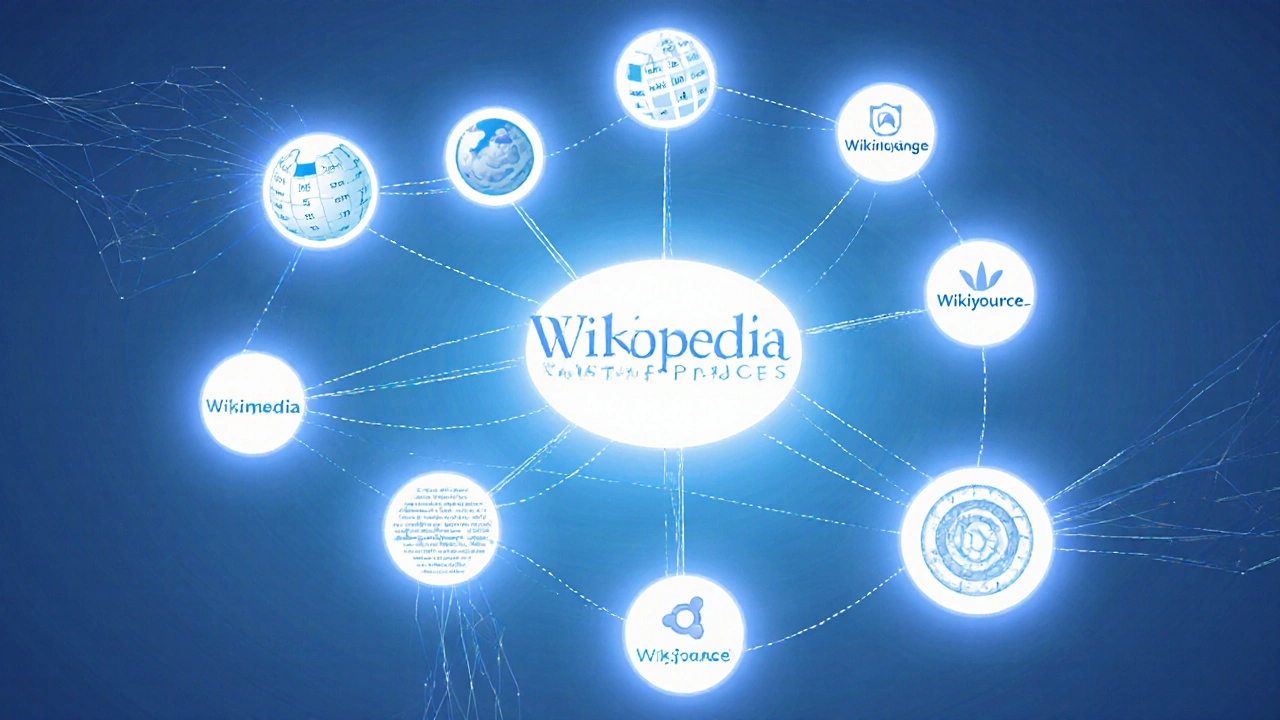

The Wikimedia Foundation doesn’t just run Wikipedia. Behind the scenes, it supports a growing network of sister projects - each built on the same open, volunteer-driven model, but serving wildly different needs. The Sister Projects Task Force was created to take a hard look at how these projects are doing, where they’re stuck, and what they need to survive and grow. This isn’t about tweaking fonts or updating logos. It’s about asking: Are these projects still fulfilling their original purpose? And if not, why?

What Are the Sister Projects?

When most people think of Wikimedia, they think of Wikipedia - the free encyclopedia with over 60 million articles in more than 300 languages. But Wikipedia is just the tip of the iceberg. The Wikimedia Foundation runs 11 official sister projects, each designed for a specific kind of knowledge sharing.

- Wiktionary - a free dictionary and thesaurus, with definitions, translations, and etymologies in hundreds of languages.

- Wikibooks - open textbooks and manuals, used by students and educators around the world.

- Wikiquote - collections of memorable quotes from public figures, books, and films.

- Wikisource - a library of free source texts: historical documents, novels, laws, and speeches.

- Wikivoyage - a travel guide written by travelers, not corporations.

- Wikinews - citizen journalism covering current events with neutral, verifiable reporting.

- Wikispecies - a directory of all species, maintained by biologists and taxonomists.

- Wikidata - the structured data backbone that powers search results, infoboxes, and AI tools across Wikimedia.

- Wikimedia Commons - a repository of over 100 million freely licensed images, audio, and video files.

- Meta-Wiki - the central hub for coordination, policy, and community discussions.

- Wikiversity - a platform for learning materials and research projects, often used by universities.

Each one started as a side experiment. Today, they’re critical infrastructure for open knowledge. But their growth has been uneven. Some thrive. Others barely breathe.

Why the Task Force Was Created

In 2023, the Wikimedia Foundation released its first-ever health check on all sister projects. The results were startling. Wikinews had fewer than 200 active editors globally. Wikispecies hadn’t updated its core taxonomy in over five years. Wikibooks was drowning in outdated textbooks with no clear path to modernization. Meanwhile, Commons was handling over 200,000 new uploads every week - but lacked the tools to manage them effectively.

The Task Force was formed in early 2024 with a simple mandate: evaluate each project’s viability, identify structural problems, and recommend actionable changes. It wasn’t about shutting things down. It was about making sure they weren’t wasting resources - or worse, misleading users.

One key finding: most sister projects rely on the same volunteer pool as Wikipedia. But Wikipedia’s growth has sucked up most of the energy. New contributors don’t even know these other projects exist. And when they do, they’re often overwhelmed by outdated interfaces, confusing guidelines, and no clear onboarding.

How the Review Process Worked

The Task Force didn’t just look at numbers. They sent out surveys, held community calls, and spent months embedded in each project’s discussion pages. They talked to longtime editors who had been there since 2005. They spoke to new contributors who tried once and quit.

Here’s what they found across the board:

- Outdated software - Most projects still run on MediaWiki 1.31, released in 2019. Many lack modern features like visual editing, mobile optimization, or AI-assisted content suggestions.

- Fragmented policies - Each project has its own rules for what counts as “reliable source” or “notable topic.” A fact that’s accepted on Wiktionary might be flagged as original research on Wikisource.

- No cross-project visibility - A photo uploaded to Commons might be used in a Wikipedia article, a Wikivoyage guide, and a Wikibooks textbook - but there’s no system to track how often it’s used or if it’s outdated.

- Lack of funding - Commons gets most of the attention because it’s visual. Text-based projects like Wikisource and Wiktionary get barely any grants or developer time.

The Task Force also noticed something unexpected: projects with strong academic ties - like Wikispecies and Wikiversity - were more stable. Why? Because universities were assigning them as course work. Students weren’t just editing - they were learning how to cite, verify, and collaborate.

Key Recommendations

The Task Force didn’t just point out problems. They proposed concrete fixes. Here are the top three changes already being tested:

- Unified editor onboarding - A new “Wikimedia Starter Kit” will guide new users through all projects in one place. Instead of landing on Wikipedia and never hearing about Wikivoyage, users will see a menu: “Want to write about travel? Try Wikivoyage. Want to cite sources? Try Wikisource.”

- Shared infrastructure upgrade - All sister projects will migrate to MediaWiki 1.40 by mid-2026. This includes better mobile support, AI-powered suggestion tools, and automatic translation for metadata.

- Project-specific funding pools - Instead of one big pot of money for “all Wikimedia projects,” each sister project will now get a dedicated annual budget based on activity, impact, and growth potential. Wikinews, for example, will get funding to hire a part-time fact-checker.

One controversial recommendation? Merging Wikidata and Wikispecies into a single, more powerful taxonomy engine. Critics say it’s too technical. Supporters argue that species data is useless without structured links to research papers, images, and geographic data - all of which already exist in Wikidata.

What’s Changed So Far

Just six months after the Task Force released its report, things are already shifting.

Wikivoyage launched a new mobile app in July 2025 - the first sister project to get one. It now has 40% more monthly active editors. Wiktionary added pronunciation audio files for over 12,000 words after a volunteer team used AI to generate them. Wikisource began partnering with university libraries to digitize out-of-print books - and now has 20% more scanned texts than last year.

But the biggest win? Visibility. A new homepage on Wikipedia now links to the top 5 sister projects based on user interest. Click “Explore More” and you’ll see: “Read a free textbook,” “Listen to historical speeches,” or “See the latest verified news.”

These aren’t flashy changes. But they’re the kind that keep open knowledge alive.

Why This Matters Beyond Wikipedia

The sister projects are a quiet revolution. They’re the reason a student in rural Kenya can read a free biology textbook. The reason a historian in Brazil can access a 1920s newspaper archive. The reason a photographer in India can upload images without worrying about copyright.

When Google pulls a fact from Wikidata to answer a search query, it’s not pulling from a corporate database. It’s pulling from a global network of volunteers who checked the source, cited the reference, and debated the wording - all for free.

The Task Force didn’t fix everything. But it proved one thing: open knowledge doesn’t survive by accident. It survives because someone is paying attention. And now, for the first time, someone is finally paying attention to all the projects - not just the biggest one.

Are all Wikimedia sister projects still active?

Yes, all 11 official sister projects are still active, but their levels of activity vary widely. Projects like Wikimedia Commons and Wikidata have thousands of active contributors. Others, like Wikinews and Wikispecies, have smaller but dedicated communities. The Sister Projects Task Force is working to strengthen underperforming projects with better tools, funding, and visibility - not to shut them down.

Can I contribute to more than one sister project?

Absolutely. Many volunteers edit multiple projects. Someone might write a Wikipedia article about a historical event, then add the primary sources to Wikisource, upload related photos to Commons, and summarize key quotes on Wikiquote. The new Starter Kit makes it easier to move between projects without getting lost in different rules.

Why doesn’t Wikimedia just shut down the low-activity projects?

Because even small projects serve real needs. Wikispecies might have only 50 active editors, but it’s the only free, community-maintained taxonomy database for scientists worldwide. Shutting it down would force researchers to rely on paywalled or incomplete sources. The goal isn’t to eliminate projects - it’s to make them sustainable.

Is Wikinews reliable?

Wikinews follows strict neutrality and verifiability rules. All articles must cite at least two independent, published sources. Unlike traditional news sites, it doesn’t report on rumors or unverified claims. It’s slower, but more accurate. Many university journalism programs use it as a teaching tool for ethical reporting.

How can I support the sister projects?

You can start by using them. Read a Wikibook. Search for a quote on Wikiquote. Browse Commons for images to use in your own work. If you’re comfortable editing, pick a project that matches your skills - whether it’s writing, translating, uploading files, or coding. Even small contributions help. You can also donate to the Wikimedia Foundation and specify that you want your gift to support sister projects.