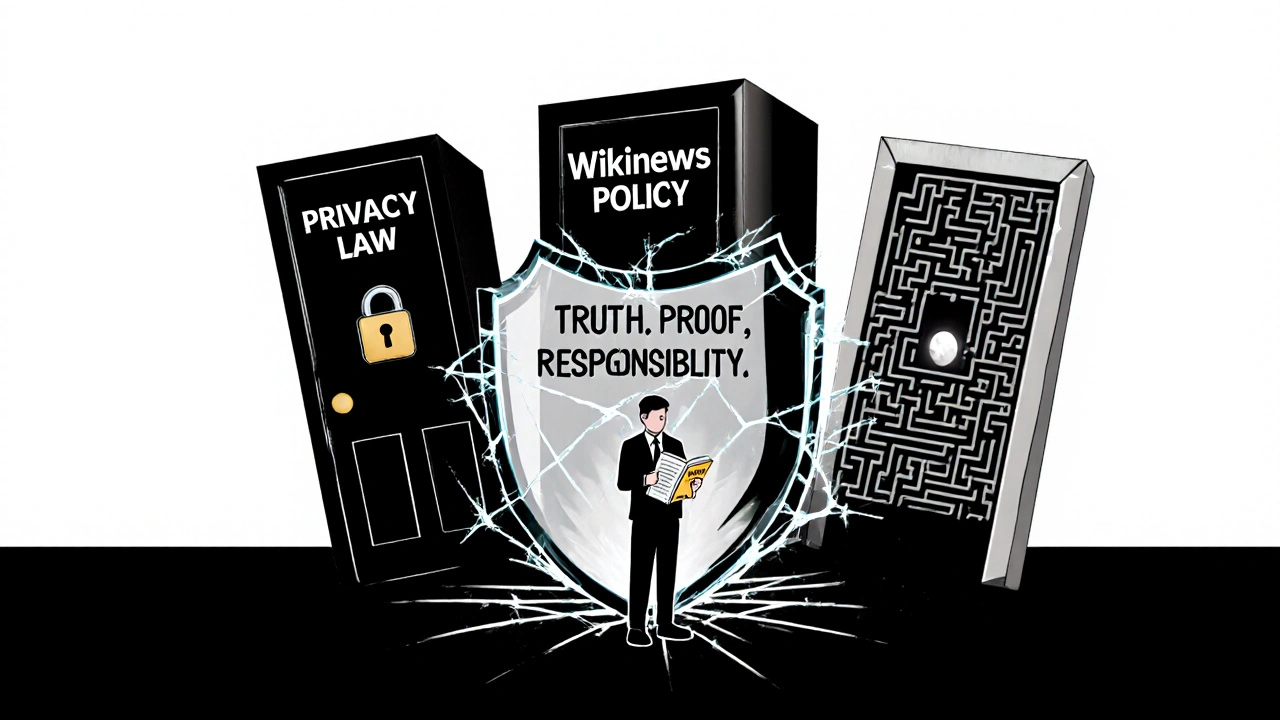

Wikinews isn’t Wikipedia. It doesn’t summarize what others have written. It publishes original reporting-by volunteers, from around the world. That’s powerful. But it’s also dangerous. If you write for Wikinews, you’re not just sharing news. You’re risking a lawsuit.

Libel Is Real, Even on a Free Platform

Libel means publishing a false statement that harms someone’s reputation. It doesn’t matter if you’re not a professional journalist. It doesn’t matter if you’re not paid. If you say someone committed a crime and they didn’t, and you can’t prove it, you’re liable.

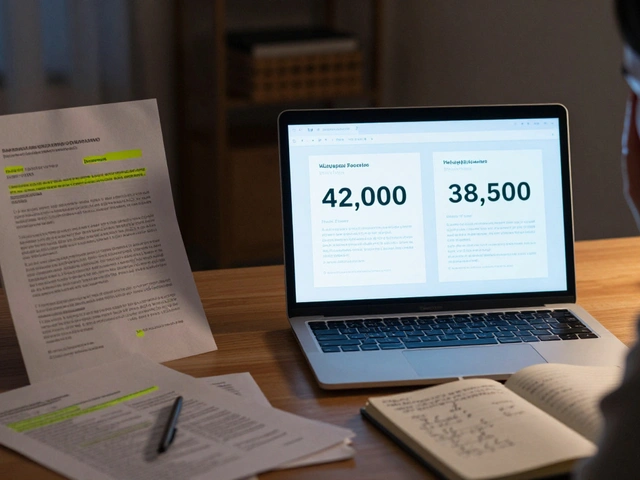

In 2023, a Wikinews contributor in Australia wrote a short article accusing a local business owner of fraud based on an unverified forum post. The owner sued. The court didn’t care that the article was labeled "user-generated." It didn’t care that Wikinews is nonprofit. The contributor had to pay over $45,000 in damages. The article was taken down, but the damage was done.

Wikinews has a policy: "All claims must be supported by reliable sources." But what counts as reliable? A press release? A blog? A tweet? Courts don’t care about your internal guidelines. They care about evidence. If you can’t show a court that your source is credible-like a government document, a court transcript, or a verified eyewitness statement-you’re exposing yourself.

Even if you use phrases like "allegedly" or "according to sources," that doesn’t automatically protect you. If the statement is false and damaging, and you published it without reasonable care, you’re still at risk.

Privacy Violations Are Easier Than You Think

Privacy isn’t just about secrets. It’s about context. Publishing someone’s name, address, or photo in a news article might be fine if they’re a public official. But if they’re a bystander in a crime scene, a victim of assault, or just someone caught in a bad moment-you could be breaking the law.

In the U.S., the First Amendment gives journalists broad rights. But those rights don’t extend to publishing private facts that are not of legitimate public concern. In 2024, a Wikinews article about a protest in Portland included the full name and home address of a participant who wasn’t a public figure. The person received threatening messages. They sued for invasion of privacy. The court ruled that Wikinews had no public interest justification for publishing private details that weren’t essential to the story.

Same thing happens in Europe. Under GDPR, even posting someone’s name without consent can be illegal if it’s not necessary for reporting. If you’re writing about a minor, a victim of domestic violence, or someone who hasn’t publicly sought attention, you need to ask: Is this detail truly needed? Could it cause harm? If the answer is yes, don’t include it.

Wikinews encourages anonymity for sources. But if you’re the writer, you’re not anonymous. Your IP address, your editing history, your username-those can all be traced. Courts can force Wikimedia to hand over your identity if someone sues.

Jurisdiction Is a Minefield

Here’s the thing: Wikinews is hosted in the U.S. But you could be in Brazil. Or Nigeria. Or Canada. And the person you wrote about could be in Germany.

That means you’re subject to the laws of every country where someone reads your article. If you write something defamatory about a French citizen, and they read it in Paris, they can sue you in France-even if you live in Ohio. French courts don’t care that you didn’t know French libel law. They care that your words reached their citizen.

Libel laws vary wildly. In the U.S., public figures must prove "actual malice"-that you knew it was false or didn’t care. In the U.K., the burden is on you to prove it’s true. In India, you can be jailed for defamation. In Germany, even quoting a false statement without correcting it can be illegal.

Wikinews doesn’t have a global legal team. You’re on your own. If someone sues, you won’t get legal support from the Wikimedia Foundation. They protect their platform, not individual writers.

And here’s the kicker: you don’t need to be in the same country to be sued. A plaintiff can file in their own country and then try to collect your assets-or your future income-across borders. A German court could freeze your PayPal account. A Canadian court could block your bank transfers.

What You Can Do to Stay Safe

You don’t have to quit writing. But you need to change how you write.

- Only report what you can prove. Don’t rely on rumors, anonymous tips, or social media. Use official documents, court records, or interviews with named, verified sources.

- Don’t name people unless necessary. If someone isn’t a public figure, ask: Does the public need to know their name? If not, use "a resident of X city" or "a witness."

- Double-check your sources. If you’re quoting a tweet, verify the account is real. If you’re citing a blog, check if it’s been debunked. Use fact-checking tools like Snopes or Reuters Fact Check.

- Use disclaimers wisely. Saying "this is not legal advice" or "this is opinion" doesn’t protect you from libel or privacy claims. Only truth and public interest do.

- Know your audience. If you’re writing about a local event in Japan, learn Japanese privacy laws. If you’re reporting on a European politician, understand EU data rules.

Some editors on Wikinews use a simple rule: "If I wouldn’t say this on national TV, I won’t write it here." That’s a good starting point.

What Happens When You Get Sued

If someone threatens legal action, don’t ignore it. Don’t delete the article and hope it goes away. That can look like evidence of guilt.

First, preserve everything: your drafts, your sources, your communication logs. Even deleted edits are stored in Wikinews history.

Second, contact a lawyer-preferably one who knows media law. Many offer free initial consultations. Some legal aid groups specialize in digital journalism.

Third, consider a retraction. If you made a mistake, correct it publicly and clearly. A prompt, honest correction can reduce damages. But don’t admit guilt unless your lawyer says so.

Most lawsuits never go to trial. But the cost to defend yourself-legal fees, time, stress-can be crushing. That’s why prevention matters more than damage control.

Who Else Is at Risk?

You’re not alone. Thousands of people write for Wikinews. Most don’t know the risks. A 2024 study by the Knight Foundation found that 72% of volunteer journalists on open platforms like Wikinews had never received legal training. Only 11% knew the difference between libel and slander.

And it’s getting worse. As traditional newsrooms shrink, more people turn to open platforms to report. But the legal risks haven’t shrunk. They’ve grown.

Wikinews is a tool for transparency. But tools can cut both ways. A well-intentioned report can destroy someone’s life. A careless quote can end your career-or your freedom.

Writing for Wikinews isn’t just about sharing facts. It’s about responsibility. You’re not just a writer. You’re a publisher. And publishers are held to the highest standard.

Can I be sued for something I wrote on Wikinews even if I didn’t get paid?

Yes. Payment has nothing to do with legal liability. Courts look at whether you published false, harmful information, not whether you were paid. Volunteer journalists are held to the same legal standards as professional reporters.

Does Wikinews protect its writers from lawsuits?

No. The Wikimedia Foundation provides hosting and technical support, but it does not offer legal defense, insurance, or financial protection to individual contributors. You are personally responsible for any legal consequences of your writing.

Can I use anonymous sources on Wikinews without legal risk?

Using anonymous sources increases legal risk. Courts often require journalists to reveal sources if they’re central to a defamation case. If you can’t verify the source’s credibility or provide documentation, your article becomes vulnerable. Anonymous tips are useful for leads-but not for publishing facts.

What’s the safest way to report on a controversial event?

Stick to official records: court documents, police reports, government statements. Quote directly. Attribute everything. Avoid speculation. If you’re unsure whether a detail is necessary, leave it out. It’s better to publish less and stay safe than to publish more and get sued.

Can I be held responsible if someone else edits my article and adds false information?

Potentially. If you published the article and it contained false information-even if added later-you may still be considered a publisher under the law. Always monitor your articles after posting. If someone edits in false claims, revert them immediately and document the change. Ignoring harmful edits can be seen as negligence.