Wikipedia claims to be the free encyclopedia anyone can edit. But if you search for Indigenous peoples - the Navajo, the Māori, the Sami, the Yolŋu - what you find often feels incomplete, outdated, or even wrong. It’s not that these communities don’t exist. It’s that their stories, histories, and knowledge aren’t being told the way they should be. And that’s not an accident. It’s a systemic issue rooted in who gets to write, who gets to edit, and whose knowledge counts.

What’s Missing When Indigenous Voices Are Absent

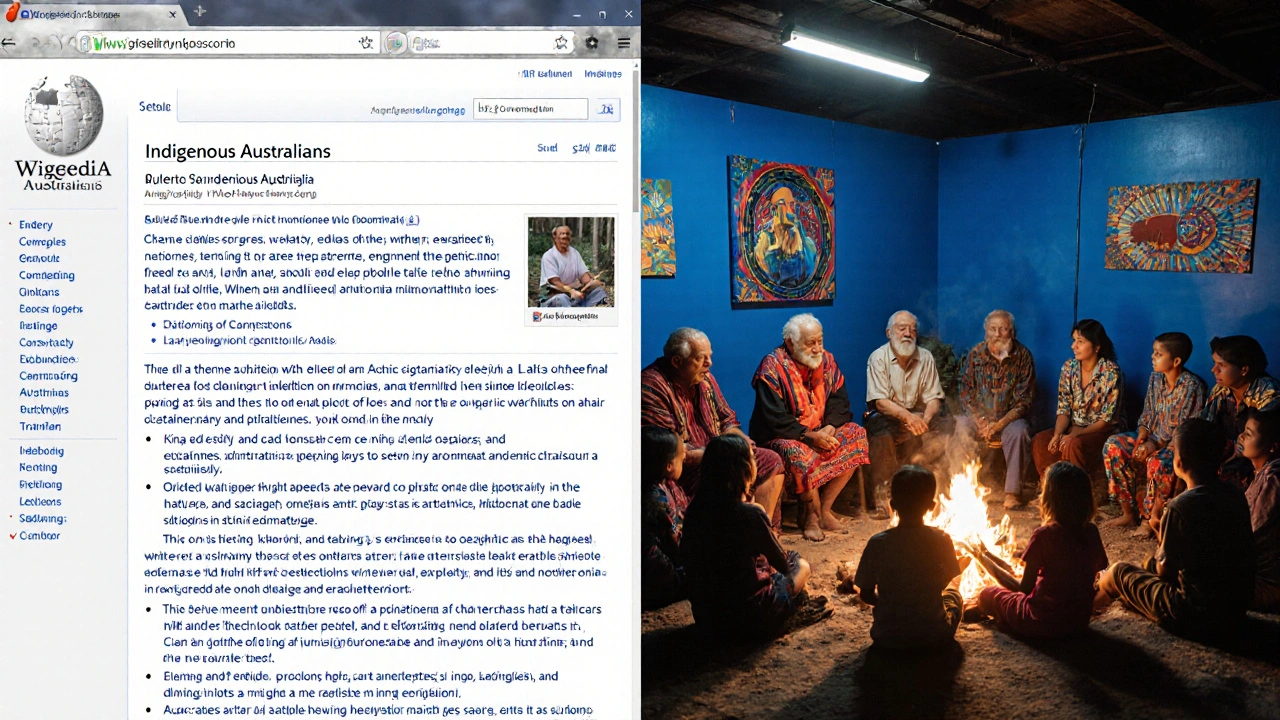

Look up the term "Indigenous Australians" on Wikipedia. You’ll find pages on colonization, land rights, and the Stolen Generations. But you won’t find detailed entries on the 250+ distinct language groups, their cosmologies, or how oral traditions function as living archives. Instead, you’ll get broad summaries written mostly by non-Indigenous editors using colonial-era sources.

Take the Navajo Nation. Wikipedia has a page on "Navajo people," but it barely mentions the Diné Bizaad language revival programs, the role of hózhó (balance and harmony) in daily life, or how traditional healing practices are integrated with modern medicine. These aren’t minor details - they’re central to understanding Navajo identity. Yet they’re absent because few editors who understand them are active on Wikipedia.

This isn’t just about missing facts. It’s about erasure. When Wikipedia reduces complex cultures to bullet points about "traditions" and "ceremonies," it flattens living societies into museum exhibits. And when editors delete content because it’s "not notable" - like a local Indigenous artist’s mural project or a community-led language class - they’re enforcing a standard of significance that was never designed for Indigenous ways of knowing.

Who’s Really Writing These Articles?

Studies show that over 85% of Wikipedia editors are male, and the majority live in North America and Western Europe. Less than 2% identify as Indigenous. That imbalance shapes what gets written - and what gets deleted.

Here’s how it plays out: An Indigenous educator in New Zealand adds a paragraph about Māori oral histories to the Wikipedia page on "New Zealand history." Another editor, based in Germany, flags it as "original research" because it’s not cited in academic journals. But Māori knowledge is passed down orally - not in peer-reviewed papers. So the edit gets reverted. The educator tries again. Same result. After a few rounds, they give up.

This happens constantly. Indigenous contributors are often told their knowledge doesn’t meet Wikipedia’s "verifiability" standard - even when that standard is built on Western academic norms that exclude Indigenous epistemologies. The result? A platform that claims to be open and free, but only if you speak its language.

The "Notability" Problem

Wikipedia’s notability guidelines were designed for Western institutions: universities, governments, corporations. They don’t work for Indigenous communities.

For example, a small Indigenous-led environmental group in the Amazon that’s protected 50,000 acres of rainforest using traditional land stewardship might not be "notable" enough for a Wikipedia page - even though it’s been featured in three national newspapers and received a UN award. Meanwhile, a corporate mining company with a $2 million PR campaign gets a full page because it’s "publicly traded."

Or take the case of the Sámi Parliament in Norway. It’s an elected government body with real authority over land use and language policy. But for years, its Wikipedia page was tagged as "stub" - incomplete - because editors kept removing details about its cultural role, calling them "non-essential." Only after Sámi activists pushed back did the page expand to reflect its true function.

Wikipedia’s rules say: "If it’s notable, it belongs." But who decides what’s notable? And why does that decision-making power rest mostly with people who don’t live these realities?

What’s Being Done Right?

Change isn’t impossible. In fact, there are powerful examples of Indigenous communities taking back control of their representation on Wikipedia.

In Canada, the Indigenous Wikimedians of Canada a volunteer group of Indigenous editors and allies who organize edit-a-thons and train community members to contribute to Wikipedia has hosted over 40 edit-a-thons since 2018. They’ve created more than 1,200 new articles on Indigenous languages, artists, activists, and historical events. One of their most impactful projects was documenting the life of Elsie Paul, a Tsleil-Waututh elder and knowledge keeper, whose oral histories were previously only available in archived interviews.

In Australia, the WikiProject Indigenous Australia works with universities and community centers to train Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in editing. They’ve added over 800 new entries, including detailed pages on kinship systems, Dreaming stories, and Indigenous science - topics that were either missing or misrepresented.

In Sweden, Sámi students at Umeå University started a Wikipedia course in 2021. By 2023, they’d doubled the number of Sámi-language articles on Wikipedia. One student, Aili Keskitalo, added a full article on Sámi joik singing - a traditional vocal form - using recordings and interviews from her own family. The article now has over 20,000 views a year.

These aren’t just edits. They’re acts of reclamation. When Indigenous people write their own stories on Wikipedia, they’re not just adding facts - they’re challenging the idea that knowledge only counts if it’s written by outsiders.

Why This Matters Beyond Wikipedia

Wikipedia is the fifth most visited website in the world. For many people, especially students and researchers, it’s the first - and sometimes only - place they look for information about Indigenous cultures.

If Wikipedia says the Inuit have no written history, people believe it. If it says the Maori are just "a tribe of New Zealand," that becomes common knowledge. And when non-Indigenous people use those incomplete or biased entries to teach, write papers, or make policy decisions, the harm echoes far beyond the screen.

It’s not just about accuracy. It’s about dignity. When a child from the Amazon reads Wikipedia and sees their people described as "primitive" or "mysterious," they internalize that message. When a young Indigenous person searches for their grandmother’s name and finds nothing, they feel invisible.

Wikipedia doesn’t just reflect the world. It shapes how we see it. And right now, it’s failing Indigenous communities by letting colonial biases go unchallenged.

What Can Be Done?

Fixing this isn’t about asking Indigenous people to play by Wikipedia’s rules. It’s about changing the rules themselves.

- Recognize oral history as valid source material. Wikipedia should allow citations from community elders, recorded interviews, and culturally approved archives - even if they’re not in academic journals.

- Create Indigenous-specific notability guidelines. A community-led land protection project that’s lasted 30 years deserves a page, even if it doesn’t have a corporate website.

- Partner with Indigenous organizations. Universities, libraries, and cultural centers should sponsor edit-a-thons and pay Indigenous editors for their time. Their knowledge is labor.

- Support Indigenous-language Wikipedia editions. There are only 10 Indigenous-language Wikipedias out of over 300. More funding and training are needed to expand them.

- Train editors on cultural sensitivity. Wikipedia’s conflict resolution tools should include mandatory training on Indigenous epistemologies for editors who revert content about Indigenous topics.

Some of this is already happening. But it’s scattered. What’s needed is a coordinated, resourced global effort - led by Indigenous communities, not just supported by them.

Final Thoughts

Wikipedia has the power to be the most inclusive encyclopedia ever built. But that won’t happen by accident. It will only happen when the people who’ve been erased from history are given the tools - and the authority - to write their own stories.

The knowledge is there. The will is growing. What’s missing is the institutional will to change the system that’s kept it out for so long.

Why doesn’t Wikipedia have more articles on Indigenous peoples?

Wikipedia lacks Indigenous content because most editors are non-Indigenous and follow Western academic standards that don’t recognize oral traditions, community knowledge, or non-Western forms of authority. Many Indigenous topics are flagged as "not notable" because they don’t meet criteria designed for corporations and universities, not Indigenous nations.

Can Indigenous people edit Wikipedia?

Yes, anyone can edit Wikipedia - including Indigenous people. But many face barriers: lack of time, digital access, or technical training. Worse, their edits are often reverted because editors don’t understand Indigenous knowledge systems. Groups like Indigenous Wikimedians of Canada and WikiProject Indigenous Australia are working to remove those barriers.

Is Wikipedia biased against Indigenous cultures?

Yes, by design. Wikipedia’s policies - like verifiability and notability - are based on Western academic norms that exclude Indigenous ways of knowing. This creates systemic bias. Articles on Indigenous topics are often shorter, outdated, and written by outsiders. Indigenous communities are actively working to fix this, but they’re fighting against entrenched systems.

What’s the biggest challenge in improving Indigenous coverage on Wikipedia?

The biggest challenge is power. Who gets to decide what counts as knowledge? Right now, that power rests mostly with non-Indigenous editors who don’t live these cultures. Real change requires shifting that power - funding Indigenous editors, recognizing oral sources, and rewriting Wikipedia’s rules to include diverse epistemologies.

Are there any success stories?

Yes. In Canada, Indigenous Wikimedians have created over 1,200 new articles on Indigenous languages, artists, and activists. In Australia, WikiProject Indigenous Australia added 800+ entries on kinship systems and Dreaming stories. In Sweden, Sámi students doubled the number of Sámi-language articles. These aren’t just edits - they’re acts of cultural survival.