Multilingual Wikipedia: How Language Editions Shape Global Knowledge

When you think of Wikipedia, you might picture the English version—but the real power lies in its multilingual Wikipedia, a network of over 300 independent language editions, each edited by local volunteers using the same open-source platform. Also known as the Wikipedia language editions, this system lets someone in Nigeria, Nepal, or Norway write and edit articles in their own language, using sources they trust and topics that matter to their community. It’s not just translation. It’s reinvention. Each edition has its own rules, priorities, and culture. The German Wikipedia values depth and citations above all. The Japanese edition leans on consensus and quiet collaboration. The Arabic version fights misinformation in a region where reliable sources are scarce. And the Swahili edition? It’s building knowledge where few encyclopedias ever existed.

The Wikimedia Foundation, the nonprofit that supports Wikipedia’s infrastructure and funding. Also known as WMF, it doesn’t control content—but it does provide the tools, servers, and legal backbone that keep all language editions running. But the real work? That’s done by volunteers. Someone in Brazil adds details about local flora. A teacher in Ukraine updates war-related articles with firsthand accounts. A student in Indonesia translates a medical guide from English to Bahasa Indonesia—not because they’re paid, but because they believe knowledge should be free, no matter the language. These aren’t outliers. They’re the norm. Over 100 language editions have more than 100,000 articles. Some, like Cebuano and Swedish, have more articles than English—but fewer readers. Why? Because those editions serve their local communities first. And that’s the point.

There’s a gap between size and impact. The English Wikipedia gets most of the attention, but the fastest-growing editions are often in languages spoken by millions who’ve been left out of global knowledge systems. The Wikipedia community, the global network of editors, administrators, and policy-makers who shape how content is created and maintained. Also known as Wikipedians, they’re the ones pushing for better representation of Indigenous languages, minority dialects, and under-documented histories. They run campaigns to add articles on African medicine, Indigenous astronomy, and regional folklore. They fix bias. They build tools to help editors move between languages. They argue over policy. They delete bad content. They do it all without pay, often under pressure, and sometimes in danger.

What you’ll find in this collection isn’t just a list of articles. It’s a window into how knowledge moves across borders—not through corporate algorithms, but through people. You’ll see how volunteers fight to keep local history alive, how AI threatens to drown out minority voices, and how a single editor in a small town can change how the world understands a place. This isn’t about one language. It’s about who gets to write the story—and who gets left out when they don’t.

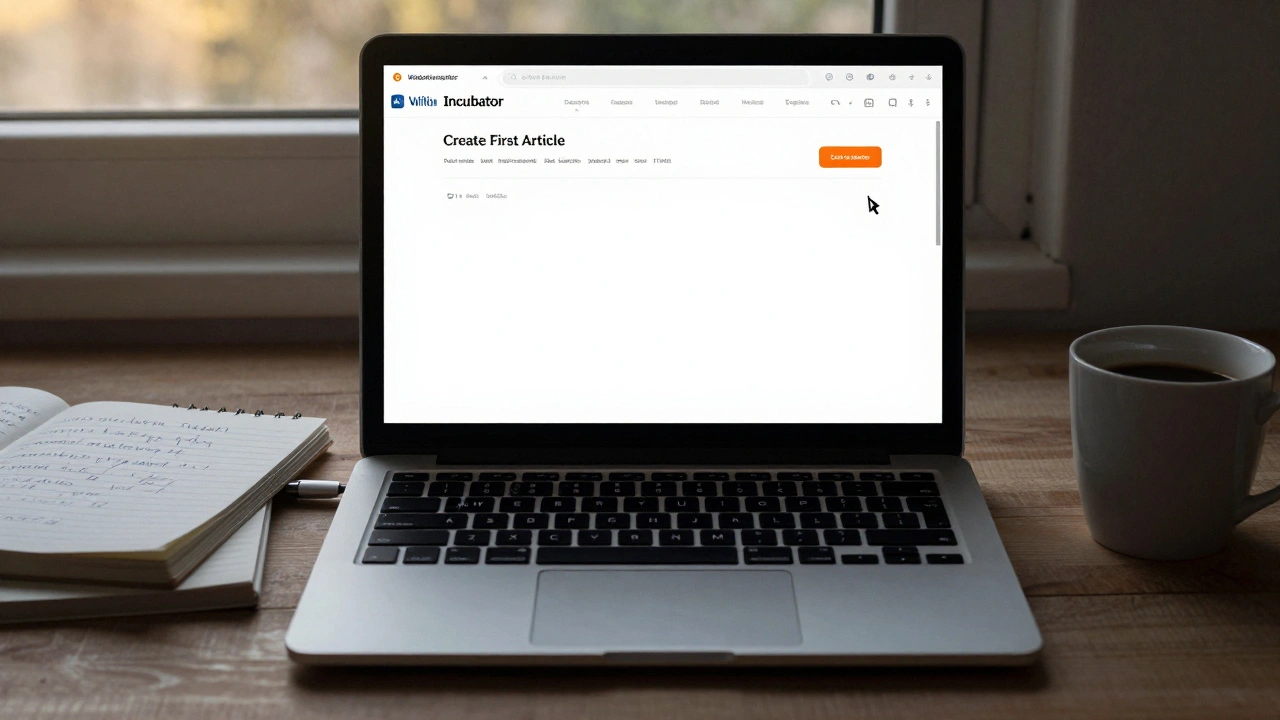

How to Build a New Wikipedia: Incubator Projects and Launch Milestones

Learn how to launch a new multilingual Wikipedia using the Wikimedia Incubator. Discover the five key milestones, common pitfalls, and real examples of successful language projects that went from zero to live.

How Wikimedia Foundation Supports Smaller Language Communities on Wikipedia

The Wikimedia Foundation supports hundreds of small-language Wikipedias through grants, translation tools, and community training - helping preserve languages that tech companies ignore.

How to Track Global Events Across Wikipedia Languages Using Interlanguage Links

Interlanguage links on Wikipedia connect articles about the same global event across dozens of languages, offering deeper, more diverse perspectives than any single version. Learn how to use them to track real-world events beyond English media.

How Wikipedia Language Editions Differ in Content, Style, and Coverage

Wikipedia's language editions differ in content, focus, and tone-not just in translation. Discover how cultural priorities shape what's included, omitted, and emphasized across global versions.

How Language-Specific Policies Differ Across Wikipedias

Wikipedia's policies vary dramatically across languages due to cultural, legal, and political differences. What's allowed on English Wikipedia may be banned on Arabic or Russian versions. Understanding these differences reveals how knowledge is shaped by context.

Localization on Wikipedia: How Dates, Names, and Cultural Conventions Work Across Languages

Wikipedia adapts dates, names, and cultural formats to match local conventions across 300+ language editions, ensuring knowledge feels familiar and accurate to every reader-no matter where they are.

Script and Orthography Challenges in Non-Latin Wikipedias

Non-Latin Wikipedias face unique challenges in typing, rendering, and editing due to complex scripts like Arabic, Chinese, and Devanagari. Learn how communities are overcoming technical barriers to preserve their languages online.

Mobile-First Editing in Emerging Wikipedia Markets

Mobile-first editing is transforming Wikipedia in emerging markets, letting millions without computers add local knowledge in their own languages. This shift is making Wikipedia more diverse, accurate, and truly global.

Multilingual GLAM-Wiki Projects: Real Case Studies on Wikipedia

Multilingual GLAM-Wiki projects connect museums, libraries, and archives with Wikipedia editors to share cultural heritage in local languages. Real case studies show how Indigenous, minority, and post-colonial communities are reclaiming their stories on Wikipedia.

Wikidata as a Bridge: Connecting Wikipedia Languages with Shared Facts

Wikidata connects over 300 Wikipedia language editions by storing shared facts in one central database, ensuring consistency and enabling smaller language communities to access accurate, up-to-date information without manual translation.

Content Translation Improvements on Wikipedia: What's New for Editors

Wikipedia’s updated translation tools help editors create accurate, high-quality multilingual articles faster. New features include AI suggestions, automatic citations, and image matching - making it easier than ever to share knowledge across languages.

Measuring Coverage Parity Across Wikipedia Language Editions

Wikipedia's language editions vary wildly in coverage. Measuring parity isn't about article counts-it's about whether your language and culture are represented with depth and accuracy in the world's largest encyclopedia.