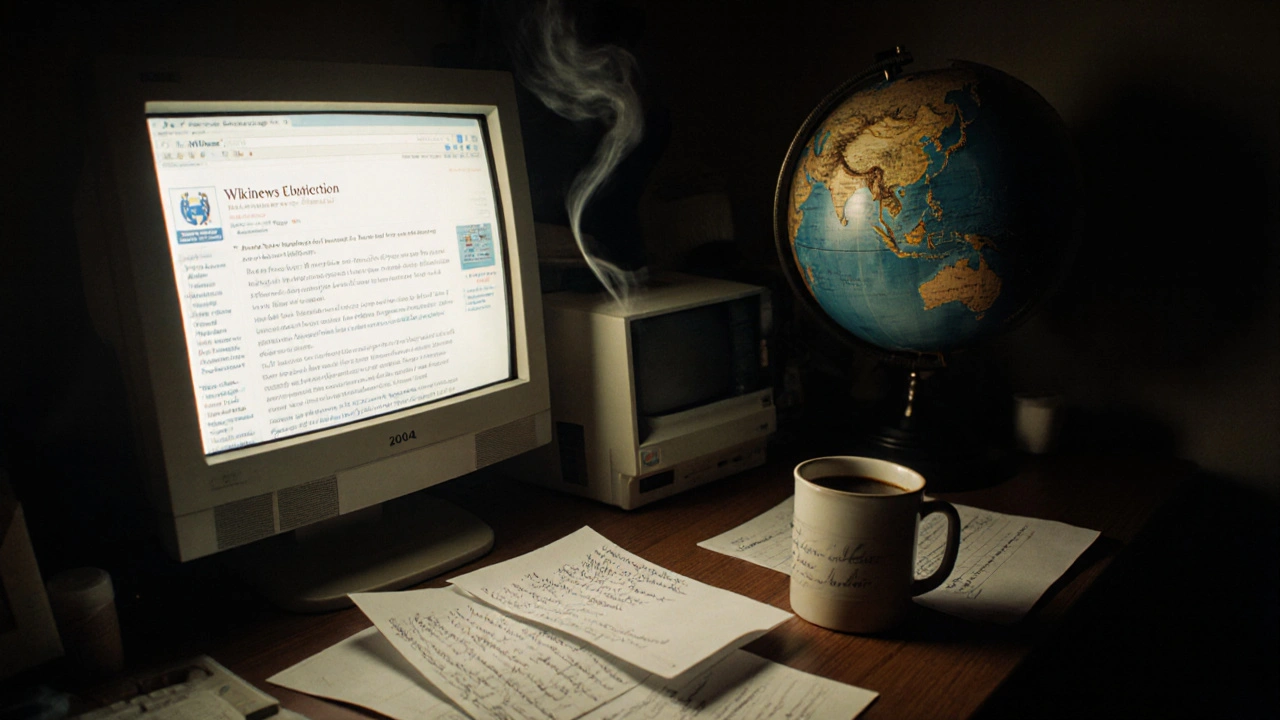

When Wikinews launched in December 2004, it wasn’t just another news site. It was a bold experiment: what if news was written not by professional reporters, but by volunteers around the world, following the same open, collaborative model as Wikipedia? No bylines, no paid staff, no corporate owners. Just facts, sourced, verified, and rewritten by anyone who cared to contribute. Ten years later, most people still don’t know it exists. But for those who do, Wikinews remains one of the most radical ideas in digital journalism - and its story tells us a lot about how the internet changed the way we understand truth.

Birth of a New Kind of Newsroom

Wikinews was born out of Wikipedia’s growing success. By 2004, Wikipedia had proven that thousands of strangers could collaboratively build a free encyclopedia. Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger, Wikipedia’s founders, wondered: could the same model work for news? Traditional media was slow, expensive, and often biased. What if real-time reporting could be done by a global network of volunteers, using Wikipedia’s open-editing tools?

The first article, published on December 4, 2004, was a short report about a Canadian election. It wasn’t flashy. No headlines. No opinion. Just facts: who ran, where, and what the results were. The tone was dry, neutral, and oddly refreshing. Unlike mainstream outlets, Wikinews didn’t chase clicks. It chased accuracy. Contributors were expected to cite sources - links to official documents, press releases, or verified media reports. No speculation. No anonymous tips. If you couldn’t prove it, you didn’t write it.

This wasn’t just a website. It was a new set of rules for journalism. And it worked - at first.

Early Growth and the Promise of Citizen Reporting

By 2005, Wikinews had grown to over 1,000 active contributors across 15 languages. Volunteers in Brazil covered protests in São Paulo. Students in India reported on local elections. Retirees in Germany fact-checked government statements. The site didn’t need a budget - it ran on goodwill and free hosting from the Wikimedia Foundation.

One of its biggest early wins came in 2005, when Wikinews published the first public transcript of a leaked U.S. State Department cable. The story broke days before major outlets picked it up. Unlike traditional journalism, where leaks often come from single sources, Wikinews had multiple contributors cross-checking the document, verifying timestamps, and linking to archived versions. It wasn’t sensational. But it was trustworthy.

That same year, the BBC and The Guardian wrote about Wikinews as a potential model for the future of news. Academics at MIT and Stanford studied it as a case in open collaboration. For a brief moment, it looked like Wikinews might become the foundation of a new kind of public media - decentralized, transparent, and free from advertising pressure.

The Challenges of Scale and Sustainability

But scaling a volunteer-run news site is harder than building an encyclopedia. Wikipedia’s articles can sit unchanged for years. News needs to be fresh. It needs to move fast. And fast-moving news requires constant attention - someone has to monitor breaking events, verify sources in real time, and update stories as new information comes in.

By 2007, the momentum slowed. Contributors burned out. The site had no editorial staff to train new writers or enforce standards. A few dedicated volunteers kept things running, but the number of active contributors dropped by 60% in two years. The site’s content became patchy. Some sections had daily updates. Others hadn’t been touched since 2006.

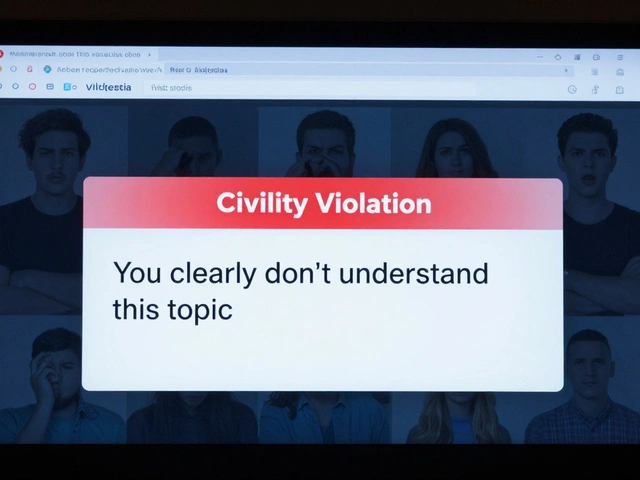

Another problem: credibility. Without a clear editorial hierarchy, it was hard for outsiders to know who was responsible for what. A story might be written by a high school student in Poland, edited by a retired journalist in Canada, and fact-checked by a university researcher in Japan. All of them were credible. But collectively, the system looked chaotic. Mainstream media didn’t cite Wikinews. Readers didn’t trust it. And without trust, it couldn’t grow.

Structural Changes and the Rise of the News Wiki

In 2010, the Wikimedia Foundation made a major change. They introduced a formal editorial process: stories had to be reviewed by at least two experienced contributors before publication. A new “News Desk” system was created, with volunteer editors assigned to different regions and topics. They started using a standardized template: headline, summary, sources, timeline, and related articles.

It helped. But not enough. The site still had no funding. No marketing. No way to compete with Twitter, Reddit, or even Google News for attention. While other platforms used algorithms to push breaking stories, Wikinews relied on word-of-mouth. If you didn’t already know it existed, you’d never find it.

By 2015, only about 150 active contributors remained worldwide. The English version published an average of two articles per week. Most were about local elections, academic conferences, or obscure policy changes. Big events - wars, elections, disasters - were often covered by other Wikinews language editions, not the English one. The site had become a quiet archive, not a live newsroom.

Current State: A Quiet Legacy

As of 2025, Wikinews still exists. It hasn’t shut down. It hasn’t been bought. It hasn’t been absorbed. It just… continues. The English edition has about 80 active contributors. The Spanish version is slightly larger. The Japanese edition still publishes daily summaries of government press briefings. There are 30 language editions total - but only seven have more than 10 active editors.

Every month, around 200,000 people visit the site. Most are researchers, students, or journalists looking for primary sources. Some use it to track how a story evolved over time - something no mainstream outlet offers. Wikinews keeps every version of every article. You can see how a report on a protest changed after new footage emerged. You can see who edited it, when, and why. That’s its real value: not as a news source, but as a historical record.

It’s also a living experiment in what happens when you remove money from journalism. No ads. No sponsors. No algorithms pushing outrage. Just the slow, careful work of people trying to get the facts right. That’s rare. And it’s worth preserving.

Why Wikinews Still Matters

Today, misinformation spreads faster than ever. Social media platforms reward speed over accuracy. Newsrooms cut staff and rely on wire services. Fact-checking is an afterthought. In that world, Wikinews feels almost like a relic - but not in a bad way.

It’s proof that open collaboration can produce reliable news. It’s proof that people will spend hours verifying sources if they believe in the mission. And it’s proof that journalism doesn’t need to be profitable to be valuable.

Some of the best journalism today comes from independent bloggers, local podcasts, and student-run outlets. But few of them document their process. Few of them show their sources. Few of them let you see the edits. Wikinews does. And that’s why, even with its tiny audience, it’s still important.

What’s Next for Wikinews?

There’s no grand revival plan. No Kickstarter campaign. No new funding. But there’s a quiet hope among its remaining contributors: that someone - a student, a researcher, a librarian - will rediscover it and realize what it offers.

Imagine a university course that teaches media literacy using Wikinews archives. Imagine a journalist who uses it to trace the origins of a false claim. Imagine a citizen reporter in a small town who starts a local Wikinews branch, covering city council meetings with the same rigor as the original volunteers did in 2004.

That’s the future Wikinews was built for. Not mass reach. Not viral moments. Just truth, slowly and carefully built by people who care.

Is Wikinews still active today?

Yes, but on a much smaller scale. As of 2025, the English edition has about 80 active contributors, and only seven of its 30 language editions have more than 10 regular editors. It publishes new articles daily, mostly on local events, policy updates, and academic developments. While it doesn’t cover breaking global news like major outlets, it maintains a complete, editable archive of every version of every story.

How is Wikinews different from Wikipedia?

Wikipedia is an encyclopedia - it documents established knowledge, events after they’ve settled, and concepts with lasting relevance. Wikinews is a news site - it reports on current events as they happen, using real-time sources. Wikipedia articles are stable and rarely change once finalized. Wikinews stories are updated constantly as new information emerges. Both use the same open-editing model, but Wikinews demands timeliness and sourcing that Wikipedia doesn’t require.

Can anyone write for Wikinews?

Yes. Anyone with a Wikimedia account can create or edit a story. But there are strict rules: every claim must be backed by a verifiable source - like a government report, official press release, or a reputable news outlet. Anonymous tips, social media posts, or personal opinions are not allowed. New contributors are encouraged to start by editing existing articles before writing their own. There’s no pay, no byline, and no promotion - just the chance to help build a transparent record of current events.

Why doesn’t Wikinews get more traffic?

It doesn’t have marketing, algorithms, or paid promotion. Unlike news sites that push breaking stories to your phone, Wikinews relies on people finding it through search or word-of-mouth. Most users don’t know it exists. Even when they do, they often assume it’s outdated or unreliable - not realizing it’s one of the few places where you can see how a news story evolved over time, with every edit logged and sourced. Its low traffic doesn’t mean it’s useless - it means it’s underused.

Has Wikinews ever been wrong?

Yes - but it’s one of the few news platforms that publicly shows when it was wrong. Every edit is tracked. If a story contained an error, you can see the original version, the correction, and who made the change. In 2008, a Wikinews article incorrectly reported a political figure’s resignation. Within hours, a contributor found the error, cited a government website, and updated the article. The original version remains archived, so readers can see the full history. That transparency is rare in journalism.

Wikinews never set out to be the biggest news site. It set out to be the most honest. And in a world where speed often beats truth, that’s still worth something.