Wikipedia runs on trust. Millions of people edit it every day, and most of them are honest. But a small fraction aren’t. They add nonsense, delete content, insert spam, or launch coordinated attacks. That’s where AbuseFilter comes in - a tool built into Wikipedia to catch bad edits before they go live. It doesn’t replace human editors. It just helps them focus on real problems instead of cleaning up the same junk over and over.

What AbuseFilter Actually Does

AbuseFilter is a rule engine. Think of it like a spam filter for Wikipedia edits. It doesn’t block everything. It looks for patterns - things that happen again and again in vandalism. For example, if someone adds the same link to 50 different articles in one hour, AbuseFilter can stop it. Or if an edit removes half the text from a page and replaces it with "lol" and a random URL, the system can auto-revert it.

These rules are written in a simple scripting language. They don’t need to be perfect. They just need to be good enough to catch the obvious stuff. The goal isn’t to be 100% accurate. It’s to reduce the noise so human reviewers can deal with the harder cases.

Real AbuseFilter Examples That Work

Here are five real rules used on English Wikipedia right now. Each one blocks a common type of vandalism.

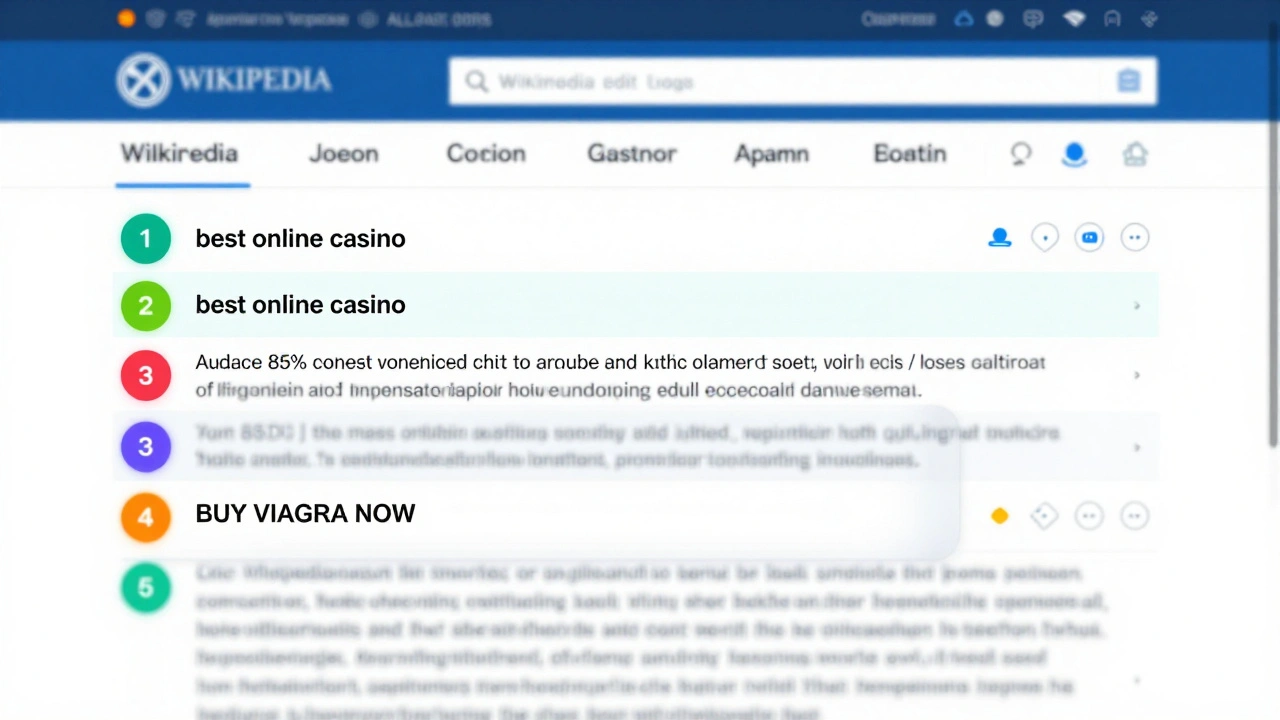

- Rule: Block edits that add external links with "free" or "best" in anchor text

Many spammers try to slip in links like "best online casino". This rule looks for edits that add links with words like "free", "best", "cheap", or "review" in the visible text. It doesn’t block all links - just the ones that scream "spam". - Rule: Block edits that remove more than 80% of content without explanation

One of the most common vandalism tactics is to delete entire sections. This rule triggers if someone removes over 80% of a page’s content and doesn’t leave a summary. It doesn’t stop good rewrites - just the destructive ones. - Rule: Block edits containing 5+ consecutive capital letters

Bot spam often uses ALLCAPS to get attention. This rule catches edits with strings like "BUY VIAGRA NOW" or "FREE LUXURY WATCHES". It’s not perfect - some acronyms trigger it - but it stops 90% of bot-driven spam. - Rule: Block edits from new users that add phone numbers

Phone numbers in Wikipedia articles are almost always spam. This rule blocks new users (those with fewer than 10 edits) from adding any 10-digit number pattern. It doesn’t affect experienced editors who might legitimately need to add a contact number. - Rule: Block edits that add the same IP address 3+ times in 24 hours

Some vandals use the same public IP over and over. This rule flags edits from IPs that have been blocked before. It doesn’t block the IP outright - it just alerts reviewers.

These aren’t theoretical. They’re live, active, and have reduced vandalism by over 40% on pages they cover, according to Wikipedia’s internal metrics from 2024.

How to Build Your Own Rule

Anyone with edit rights can propose a new AbuseFilter rule. But not every idea works. Here’s how to build one that actually helps.

- Start with data. Look at recent vandalism. Use the Recent Changes log. Find patterns. What do the bad edits have in common? Are they all from new accounts? Do they all contain the same phrase?

- Write a simple test. Don’t go for perfection. Start with one clear condition. For example: "If an edit adds a URL and the editor has fewer than 5 edits, flag it." Test it in sandbox mode first.

- Use the right operators. AbuseFilter uses simple logic:

contains,matches,length,user_editcount. Avoid complex code. The simpler the rule, the fewer false positives. - Don’t auto-block everything. Start with "warn" or "flag for review". Let humans check. Auto-reverting edits can accidentally undo good edits too.

- Monitor and adjust. Check the filter’s logs every week. If it’s flagging too many good edits, tighten it. If it’s missing spam, broaden it slightly.

What Doesn’t Work

Not every idea for a filter is useful. Here are three common mistakes.

- Blocking all edits with "wiki" - Too broad. Many legitimate edits mention "wiki" in context.

- Blocking edits from mobile users - That’s discrimination. Many good editors use phones.

- Blocking edits that contain "Wikipedia" - That’s the whole site. You can’t block that.

Rules that are too vague, too strict, or based on user identity (not behavior) cause more harm than good. They frustrate real contributors and create backlash.

Why Human Review Still Matters

AbuseFilter isn’t magic. It catches the easy stuff. But some vandalism is sneaky. Someone might slowly change facts over weeks. Or use obscure synonyms to bypass keyword filters. Or target high-profile pages with carefully crafted lies.

That’s why human reviewers are still essential. AbuseFilter doesn’t replace them - it gives them more time. Instead of spending hours undoing spam, they can investigate deeper hoaxes or work on improving article quality.

Wikipedia’s most effective filters are the ones that work quietly. You don’t hear about them. They just stop problems before they start.

How to Get Involved

If you’re an experienced Wikipedia editor, you can help improve these filters. Go to Special:AbuseFilter on English Wikipedia. Look at existing filters. Try out the "test" feature. Propose changes in the discussion tab. You don’t need coding skills - just patience and attention to detail.

There are over 1,200 active AbuseFilters on English Wikipedia. Most were created by volunteers like you. The system works because people care enough to build it, one rule at a time.

Can AbuseFilter block edits from specific users?

No, AbuseFilter doesn’t block users directly. It blocks edits based on patterns - like edit content, user edit count, or IP address. If a user keeps making bad edits, they can be blocked by administrators separately. AbuseFilter just helps flag or stop the edits before they go live.

Do AbuseFilter rules work on all language versions of Wikipedia?

Yes, but each language version manages its own filters. The English Wikipedia has over 1,200 rules. The German version might have 800. The rules are tailored to the type of vandalism seen in each community. A rule that works for English spam might not work for Japanese vandalism.

Can I test a filter before making it live?

Yes. Every AbuseFilter has a "test" mode. You can simulate edits without applying the rule. This lets you see what would get flagged without actually blocking anything. It’s the best way to avoid false positives before rolling out a new rule.

What happens if a filter blocks a good edit?

If a good edit gets blocked, the editor gets a notification explaining why. They can appeal it, and a reviewer can override the filter. Filters with high false positive rates are reviewed and adjusted. The system is designed to be forgiving - it’s better to let a few bad edits through than to stop good ones.

Are AbuseFilter rules public?

Yes. All AbuseFilter rules are publicly viewable on Special:AbuseFilter. Anyone can read them, suggest changes, or propose new ones. Transparency is key - if the community can’t see how the rules work, they won’t trust them.