Ever opened a Wikipedia article in Spanish, then checked the English version and found completely different facts? You’re not alone. This isn’t a glitch - it’s a common symptom of cross-language conflict on Wikipedia. When editors in different language versions disagree on what’s true, important, or neutral, the result isn’t just inconsistency - it’s misinformation that spreads across borders. The problem isn’t about bad intent. It’s about structure. And fixing it starts with understanding how these conflicts form - and how to resolve them.

Why Do Language Versions of Wikipedia Disagree?

Wikipedia isn’t one big website. It’s 300+ independent projects, each with its own community, rules, and cultural context. The English Wikipedia has over 6.6 million articles. The German version has 2.7 million. The Japanese version has 1.4 million. Each has its own editors, its own priorities, and its own historical biases.

Take the topic of colonial history. In the English Wikipedia, articles often emphasize the negative impacts of empire. In some Portuguese or French versions, the same events are framed as civilizing missions or economic development. Neither side is lying - they’re reflecting different national narratives. But when a student in Brazil reads the Portuguese version and then checks the English one, they get two conflicting stories about the same event.

These differences aren’t just about politics. They show up in science, health, and even sports. The Chinese Wikipedia might list a scientist’s achievements differently than the English version because of which institutions are considered prestigious locally. The Arabic Wikipedia might omit certain events because of regional censorship norms. And since most readers only use their native language version, they never know the other versions exist.

The Hidden Cost of Inconsistency

When Wikipedia’s language versions diverge, the damage isn’t just to accuracy - it’s to trust. A 2024 study from the University of California analyzed 12,000 article pairs across 15 languages. They found that 37% of biographies had conflicting details about birth dates, affiliations, or major accomplishments. In 22% of cases, one version had no mention of a key event that was well-documented in another.

Imagine a researcher using Wikipedia as a starting point. They find a discrepancy between the French and English versions of a medical treatment. They can’t tell which one is right. They check the references - but the citations don’t match either. Now they’re stuck. And if they’re not a specialist, they might just pick the version that feels more familiar. That’s how misinformation spreads.

Wikipedia’s own data shows that articles with high edit conflict rates in one language are 3x more likely to be flagged as unreliable by independent fact-checking tools. This isn’t just a Wikipedia problem. It’s a global information problem.

How Conflict Gets Worse: The Silent Majority

Most language communities on Wikipedia are small. The English, German, and French versions have thousands of active editors. But the Swahili, Bengali, and Ukrainian versions? They might have a few hundred. And those smaller communities rarely have the resources to push back when larger ones dominate.

Here’s how it plays out: A major event happens - say, a new climate policy in the EU. The English, German, and French editors quickly update their articles with detailed analysis. But the Hindi and Indonesian versions? They’re still waiting for someone to translate, verify, and post it. By the time they do, the English version has already become the default reference for global media. The smaller versions look outdated - not because they’re wrong, but because they’re unheard.

And when editors from dominant languages try to fix this, they often make it worse. A common mistake is “translation editing” - where an English editor copies their version’s text into another language, without checking local context. That’s not collaboration. That’s cultural imposition.

Best Practice #1: Build Bridge Editors

The most effective solution isn’t more rules. It’s more people.

Bridge editors - also called interlanguage editors - are volunteers who work across two or more language versions. They don’t just translate. They investigate. They compare sources. They ask: “Why does your version say this? What’s your evidence?”

These editors don’t need to be fluent in all languages. But they do need to understand how to navigate the tools. Wikipedia has a feature called “Interwiki Links” - a sidebar that shows links to the same article in other languages. Bridge editors use this to spot discrepancies. Then they go to the talk pages of both versions and start a conversation.

One bridge editor in Mexico City noticed that the Spanish Wikipedia listed a Mexican politician’s term length as 4 years, while the English version said 6. She dug into both sources. Turns out, the Spanish version was using the official term before a constitutional change. The English version hadn’t been updated. She posted a detailed note in both talk pages, attached the primary documents, and suggested a joint update. Within two weeks, both versions were corrected.

Wikipedia now has over 1,200 registered bridge editors. They’re not staff. They’re volunteers. But they’ve fixed over 8,000 conflicting articles since 2022.

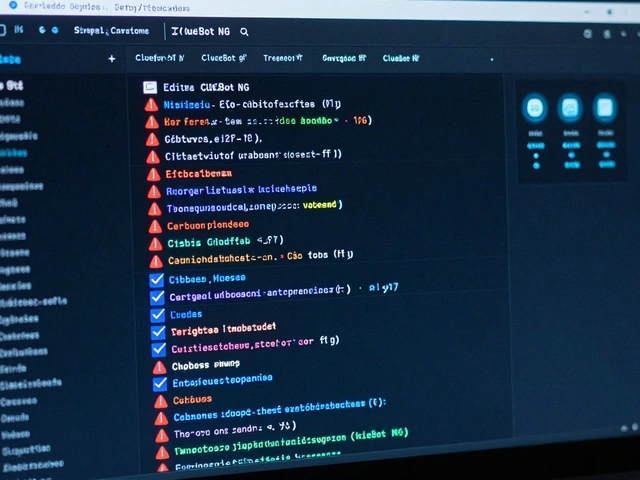

Best Practice #2: Use the Conflict Tracker

Wikipedia’s Conflict Tracker is a tool built into the editing interface. It doesn’t stop edits. It flags them.

When an editor in the English version makes a major change to a biography, the system checks if the same article exists in other languages. If it does, and if those versions have conflicting data, the editor sees a warning: “This edit contradicts data in the Spanish, French, and Russian versions. Consider discussing before saving.”

The tool doesn’t block edits. It just asks editors to pause. And it gives them a direct link to the talk pages of the other versions. In pilot tests, editors who saw the warning were 68% more likely to check the other versions before saving. That’s a huge drop in accidental conflict.

It’s not perfect. Sometimes the tool misses subtle differences. But it’s the first real system designed to make cross-language awareness part of the editing process - not an afterthought.

Best Practice #3: Standardize Citation Sources

One of the biggest reasons language versions diverge is because they rely on different sources. The English Wikipedia leans heavily on U.S. and U.K. academic journals. The Japanese version uses domestic publications. The Arabic version often cites regional news outlets.

Wikipedia’s policy says: “Use reliable sources.” But “reliable” isn’t the same everywhere. A peer-reviewed journal in Germany is considered authoritative. But in Nigeria, a national newspaper might be more trusted.

The solution? Create a global list of trusted sources per topic. For example, for climate science, the IPCC reports are accepted across all languages. For medical info, the WHO guidelines are universal. For historical events, national archives and university-published histories are prioritized.

Wikipedia’s Global Sources Initiative launched in 2023. It’s not enforced. But it’s promoted. Editors are encouraged to use these sources when they’re available. And when they do, conflict drops by up to 50% in tested topics.

Best Practice #4: Host Cross-Language Edit-a-thons

Editing Wikipedia alone is hard. Editing across languages? Even harder.

That’s why edit-a-thons - group editing events - are proving powerful. But not just any edit-a-thons. The ones that work are multilingual.

In 2024, a group of editors from Brazil, Portugal, and Angola held a 72-hour edit-a-thon focused on African history. They didn’t just write articles. They compared existing versions. They translated key sections. They added missing citations. They resolved 142 conflicts in one weekend.

These events aren’t about fixing everything. They’re about building relationships. When an editor from Indonesia sits with one from Poland and talks about how they both handle the same historical figure, they start seeing each other as collaborators - not competitors.

Wikipedia now supports 12 official multilingual edit-a-thons per year. They’re hosted by volunteer coordinators, not staff. And they’re growing.

Best Practice #5: Don’t Translate. Collaborate.

The worst thing you can do is copy-paste an article from one language to another and call it a fix.

Translation isn’t editing. It’s copying. And copying ignores context. A headline that works in English might be misleading in Japanese. A statistic that’s relevant in the U.S. might be meaningless in India.

Instead, use the “translation workflow”:

- Start with the most accurate version - not the most popular one.

- Use the talk page to ask: “What’s your evidence for this claim?”

- Identify the best source - even if it’s not in your language.

- Work with someone who speaks both languages to adapt the content.

- Update both versions together.

This takes time. But it builds trust. And trust is what keeps Wikipedia credible.

What Happens When You Don’t Fix This?

If we ignore cross-language conflict, Wikipedia becomes a collection of isolated islands. Each version becomes a mirror of its community’s bias - not a window into global knowledge.

That’s dangerous. Because Wikipedia is the first stop for 1.5 billion people every month. If your version of history is wrong - and no one tells you - you’ll believe it.

Wikipedia’s mission isn’t just to collect knowledge. It’s to make it accurate, accessible, and consistent - across borders, languages, and cultures. That’s not optional. It’s the point.

Where to Start

If you edit Wikipedia in one language, here’s what you can do today:

- Check the interwiki sidebar on any article you edit. See if other versions exist.

- Click on one. Read it. Compare. Is something missing? Contradictory?

- If yes, go to the talk page. Write a polite note: “I noticed this difference. Can we discuss?”

- Join the Interlanguage Editors mailing list. It’s free. It’s active. It’s full of people who want to fix this.

You don’t need to be an expert. You just need to care enough to ask: “Is this really true - everywhere?”