Every day, a student in rural Nigeria opens a phone with no internet data plan but still loads Wikipedia. They’ve saved the page offline. In a small village in Peru, a teacher prints out Wikipedia articles to use as textbooks because the school has no budget for new books. In Ukraine, a teenager studying physics uses Wikipedia to understand concepts their local school can’t explain. These aren’t rare stories. They’re happening millions of times a day.

Wikipedia Isn’t Just a Website - It’s a Lifeline

Wikipedia doesn’t charge for access. It doesn’t ask for a credit card, a login, or a subscription. It doesn’t require Wi-Fi in every classroom. That’s why it’s the most-used educational resource on the planet - not because it’s perfect, but because it’s there when nothing else is.

Over 2 billion people visit Wikipedia each month. Half of them come from countries with low or middle income. In places like Bangladesh, Kenya, or Bolivia, students rely on it more than their own national education portals. Why? Because Wikipedia works on old phones. It loads fast on slow networks. It’s translated into 300+ languages - including ones that don’t have official textbooks.

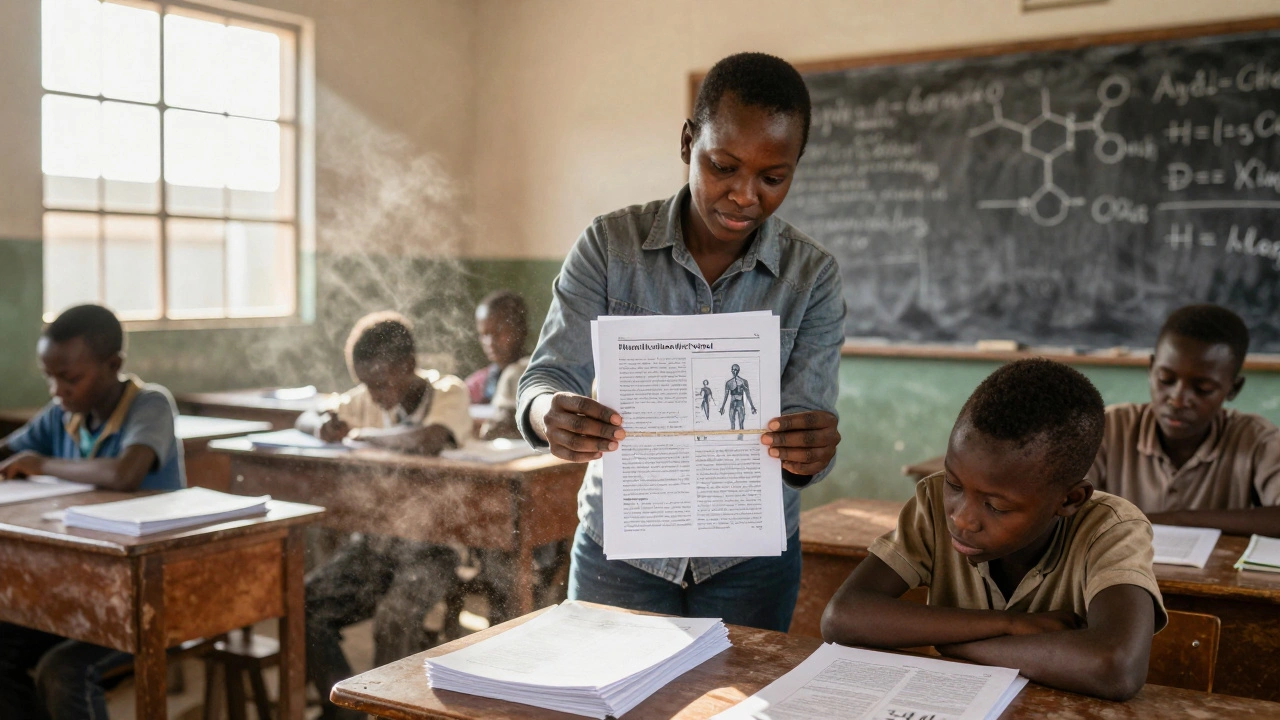

When Schools Can’t Afford Books, Wikipedia Steps In

In 2023, a study by the University of Cape Town found that 78% of public high schools in rural South Africa had no functioning library. Yet, 92% of students had access to at least one mobile phone. That gap? Wikipedia filled it.

Teachers started using Wikipedia as a primary source. They’d download articles using the offline app Kiwix, load them onto USB drives, and hand them out to students. Biology lessons on human anatomy? Done. Math formulas for grade 10? Covered. History of the African independence movements? Available in Zulu, Xhosa, and English.

It’s not about replacing textbooks - it’s about replacing silence. When there’s no textbook, there’s no explanation. When there’s no explanation, learning stops. Wikipedia doesn’t let that happen.

Language Is the Biggest Barrier - Wikipedia Breaks It

Most educational content online is in English, Mandarin, or Spanish. But over 7,000 languages are spoken worldwide. More than 1,500 of them have no written school materials at all.

Wikipedia has articles in 327 languages with over 100,000 entries. That includes languages like Quechua, Yoruba, and Maori - languages spoken by millions but ignored by commercial publishers. A child in Guatemala learning in Quechua can now read about photosynthesis in their mother tongue. A student in Nigeria studying Igbo can find a clear explanation of Newton’s laws.

These aren’t translations done by bots. They’re written by locals - teachers, nurses, farmers - who care enough to write what they know. A 16-year-old in Papua New Guinea wrote the first Wikipedia article on traditional canoe building. It’s now used in three village schools.

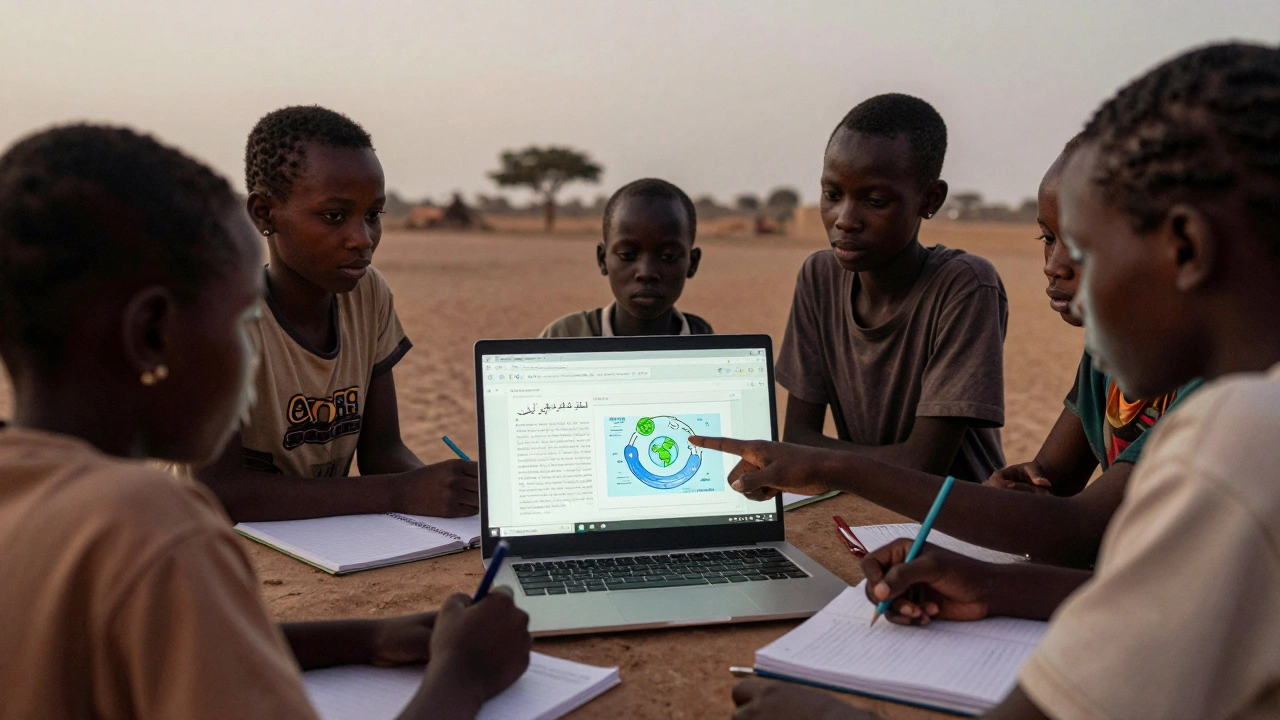

Wikipedia’s Hidden Infrastructure: Offline Access and Mobile Tools

Wikipedia doesn’t just exist online. It’s been rebuilt for places without reliable internet.

- Kiwix lets users download entire Wikipedia sections onto USB drives or SD cards. Schools in remote areas of Mongolia and Laos use it to run Wikipedia from a single laptop.

- Wikipedia Zero (now replaced by partnerships with mobile carriers) once gave free data access to Wikipedia in 70+ countries. Even after it ended, carriers in India and Egypt kept zero-rating Wikipedia because students used it so heavily.

- Wikipedia for Schools is a curated version of 5,000 vetted articles, designed for classrooms. It’s used in 40 countries, including refugee camps in Jordan and camps for displaced children in South Sudan.

These tools aren’t gimmicks. They’re survival tools for education.

Why Wikipedia Works When Other Platforms Fail

Other free learning platforms - like Khan Academy or Coursera - require accounts, stable internet, and often English fluency. They’re designed for people who already have access.

Wikipedia was built for the opposite: people who don’t.

It’s open. Anyone can edit. Anyone can use. No gatekeepers. No paywalls. No algorithm hiding content because you didn’t click enough ads. It doesn’t care if you’re rich or poor, literate or learning to read. It gives you the facts - in the language you speak, on the device you own.

And it’s constantly improving. Every edit, every correction, every translation adds to a global public library - one that’s free, alive, and growing.

It’s Not Perfect - But It’s the Best We’ve Got

Yes, Wikipedia has errors. Yes, some articles are incomplete. Yes, vandalism happens. But here’s the thing: every mistake gets fixed - often within minutes.

Compare that to a printed textbook that costs $80 and sits on a shelf for 10 years with outdated information. Or a government education site that hasn’t been updated since 2018.

Wikipedia’s strength isn’t in being flawless. It’s in being responsive. A student in Brazil notices a wrong date in the article on the Amazon rainforest? They fix it. A teacher in Nepal adds a diagram to the article on monsoon patterns? It’s live by morning. The system works because it’s owned by the people who use it.

Real Impact: Numbers That Matter

- In India, a 2024 survey found that 63% of rural high school students used Wikipedia as their main source for science homework - more than any textbook or teacher.

- In Egypt, over 1.2 million students accessed Wikipedia through mobile data partnerships in 2025 - a 40% increase from the year before.

- UNESCO reported that countries with high Wikipedia usage in low-income regions saw a 17% higher rate of students completing secondary education compared to similar countries without it.

These aren’t guesses. They’re measurable outcomes. Wikipedia isn’t just helping students learn - it’s helping them stay in school.

What Happens When Wikipedia Isn’t Available?

In 2023, Sudan’s civil war shut down internet access for months. Schools closed. Books burned. But students in refugee camps still found ways to access Wikipedia - through USB drives passed hand to hand, through printed pages smuggled across borders.

When a student in Khartoum told a journalist, “I don’t have a school, but I still have Wikipedia,” it wasn’t poetic. It was true.

Wikipedia doesn’t solve poverty. It doesn’t fix broken governments. But it does something quieter, deeper: it gives people the right to know. And in places where education is a privilege, that right is everything.

Wikipedia Is the Only Global Classroom That Doesn’t Ask for a Fee

Imagine a world where every child, no matter where they’re born, could learn about gravity, democracy, or the human heart - without paying a cent. That world exists. It’s called Wikipedia.

It’s not a replacement for teachers. It’s not a replacement for schools. But when schools are empty and teachers are unpaid and books are locked behind paywalls, Wikipedia is the only thing standing between a child and the truth.

It’s not glamorous. It doesn’t have ads. It doesn’t sell data. It doesn’t need your attention. It just works - quietly, endlessly, for everyone.

Is Wikipedia reliable enough for students to use in school?

Yes - if students learn how to use it right. Wikipedia isn’t a source you cite blindly. It’s a starting point. Every article lists its references. A student can trace a fact back to a peer-reviewed journal, a government report, or a university textbook. Many teachers now teach students to use Wikipedia as a map to credible sources - not the final destination. In fact, a 2022 study in the Journal of Educational Technology found that students who learned to evaluate Wikipedia sources performed better on research tasks than those who only used traditional textbooks.

Can people in low-income countries really access Wikipedia without data?

Absolutely. Apps like Kiwix let users download entire sections of Wikipedia onto USB drives or SD cards. Schools in remote areas load these onto one computer, then share them with dozens of students. In some places, volunteers print Wikipedia articles and bind them into booklets. In refugee camps, these printed pages are often the only learning materials available. It’s not ideal - but it’s better than nothing.

Why doesn’t Wikipedia have more content in African or Indigenous languages?

It does - but not enough. Over 300 languages have Wikipedia editions, including many African and Indigenous ones. But growth is uneven. Languages like Swahili and Yoruba have strong communities of editors. Others, like Tswana or Guarani, have far fewer contributors. The gap isn’t technical - it’s about resources and recognition. When schools and governments stop funding local language education, they also stop supporting the people who write about it online. The solution? Support local educators and community groups who are already doing the work.

Does Wikipedia replace teachers?

No. Teachers are irreplaceable. What Wikipedia replaces is the silence when teachers are absent, underpaid, or overworked. In places where one teacher handles 80 students across three grades, Wikipedia gives students a way to learn independently. It doesn’t replace guidance - it enables it. A teacher using Wikipedia as a tool can focus on explaining complex ideas instead of repeating basic facts.

How can I help expand Wikipedia’s reach in underserved areas?

Start by editing. If you speak a language with few Wikipedia articles, write or translate one. If you’re a teacher, show your students how to use it responsibly. If you’re a nonprofit, partner with Wikimedia chapters to distribute offline versions. Don’t wait for someone else to fix it - the system only works when people contribute. Even one well-written article can change a student’s future.