There are over 300 language versions of Wikipedia. Each one runs on the same software, follows the same basic mission, and looks almost identical. But beneath the surface, the rules that shape what gets written, edited, and kept vary wildly. A fact that’s perfectly acceptable on the English Wikipedia might get deleted instantly on the Arabic or Japanese version. Why? Because each Wikipedia isn’t just a translation-it’s a separate community with its own culture, history, and laws.

English Wikipedia: The Rulebook Giant

The English Wikipedia has the most editors, the most policies, and the most complex enforcement system. It’s not unusual for a single article to be governed by dozens of guidelines: Notability, Neutral Point of View, No Original Research, Verifiability, and more. These aren’t suggestions-they’re binding rules enforced by volunteer administrators who can block users, delete pages, or lock articles.

For example, if you write about a local band from Ohio, the English Wikipedia will demand multiple independent, reliable sources that mention the band. One blog post or a YouTube video won’t cut it. You need newspaper articles, music reviews from established outlets, or academic citations. If you can’t provide them, the article gets deleted-even if the band has 10,000 followers.

This strictness isn’t about being harsh. It’s about scale. With over 6 million articles, English Wikipedia can’t afford to let low-quality content pile up. The community trusts documented evidence over personal belief. That’s why celebrity gossip, rumors, and unverified claims rarely survive here.

Arabic Wikipedia: Censorship, Sensitivity, and Silence

Arabic Wikipedia operates under very different pressures. Many of its editors live in countries with strict government control over information. In places like Saudi Arabia, Egypt, or the UAE, writing about religion, politics, or sexuality can lead to real-world consequences. So the Arabic Wikipedia community has developed a culture of caution.

Articles on topics like LGBTQ+ identities, criticism of religious figures, or even historical conflicts between Arab states are often avoided entirely. If they’re written, they’re heavily sanitized. One editor told me they once spent months rewriting a page on gender identity to remove all references to non-binary identities because the term didn’t exist in formal Arabic and could trigger backlash.

Unlike English Wikipedia, where debate happens openly on talk pages, Arabic Wikipedia often resolves disputes in private messages or through silent consensus. If a topic is too risky, it just doesn’t get edited. The absence of content is a policy in itself.

Japanese Wikipedia: Consensus Over Conflict

Japanese Wikipedia doesn’t have the same volume of editors as English, but it has a deeply rooted culture of harmony. Conflict is avoided. Disagreements are settled quietly. The community prefers to let articles sit unchanged rather than argue over them.

For example, the Japanese Wikipedia doesn’t have a formal “notability” policy like English. Instead, editors ask: “Is this something people in Japan already know about?” If yes, it stays. If not, it gets removed-even if it’s well-sourced. A small-town museum in rural Japan might have dozens of articles on it, while a globally known tech startup might get deleted for being “too obscure” to Japanese readers.

Japanese editors also avoid direct criticism. You won’t find articles that call out corruption in government or corporate scandals with strong language. Instead, facts are presented neutrally, and judgment is implied. A biography of a disgraced politician might list their convictions but avoid words like “corrupt” or “fraud.”

German Wikipedia: Precision and Authority

German Wikipedia is known for its rigor. It’s less about volume and more about accuracy. Articles are expected to be comprehensive, well-structured, and heavily cited. Editors treat Wikipedia like a scholarly reference-like an academic journal you can edit.

One major difference: German Wikipedia doesn’t allow “popular culture” articles unless they have lasting cultural impact. You won’t find pages on reality TV shows, TikTok trends, or viral memes. But you will find detailed entries on obscure German philosophers, regional dialects, or 19th-century railway systems.

Also, German Wikipedia requires citations from authoritative sources. Blogs, forums, and news sites from non-reputable outlets are often rejected. Even major newspapers like Bild or BILD am Sonntag are considered unreliable because they’re tabloids. Only Süddeutsche Zeitung, Der Spiegel, or academic publications count.

And unlike English Wikipedia, where editors can debate for weeks, German editors often make decisions quickly. If three experienced editors agree an article is inaccurate, it’s deleted. No long discussions. No voting. Just consensus.

Russian Wikipedia: Politics, Censorship, and Self-Censorship

Since 2022, Russian Wikipedia has been blocked in Russia. But the community still operates from abroad, and its policies have shifted dramatically. Editors now avoid anything that could be interpreted as “anti-Russian” under the country’s laws on “false information.”

Articles about the war in Ukraine, opposition figures like Alexei Navalny, or historical events like the Soviet invasion of Hungary are heavily edited or removed. Some editors have left entirely. Others stay and write in a way that avoids direct conflict-using passive voice, omitting dates, or replacing politically charged terms with neutral ones.

For example, instead of saying “Russia invaded Ukraine,” you might see “military operations began in Ukraine in 2022.” The facts are still there, but the framing is changed to avoid legal risk. This isn’t official censorship-it’s self-preservation.

Even Wikipedia’s own neutrality policy is strained here. The community walks a tightrope: maintain accuracy while avoiding prosecution. Many articles on Russian history now read like diplomatic statements.

Chinese Wikipedia: The Missing Giant

There is no official Chinese Wikipedia in mainland China. The version that exists-written in Traditional Chinese-is hosted outside China and is blocked by the Great Firewall. Most Chinese speakers use Baidu Baike or Zhihu instead.

What’s left of Chinese Wikipedia is a small, isolated community of editors in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and overseas. Their policies are shaped by the need to avoid triggering censorship. Articles on Tibet, Taiwan, Tiananmen Square, or the Uyghur population are either heavily edited or missing entirely.

Even basic facts about Chinese politics are rewritten. For example, the term “People’s Republic of China” is used consistently, and references to “Taiwan independence” are removed. Editors know that if they push too far, the entire site could be targeted again.

As a result, Chinese Wikipedia has a huge gap in coverage. It lacks depth on modern Chinese society, economics, and culture. The community survives, but it can’t grow.

Why These Differences Matter

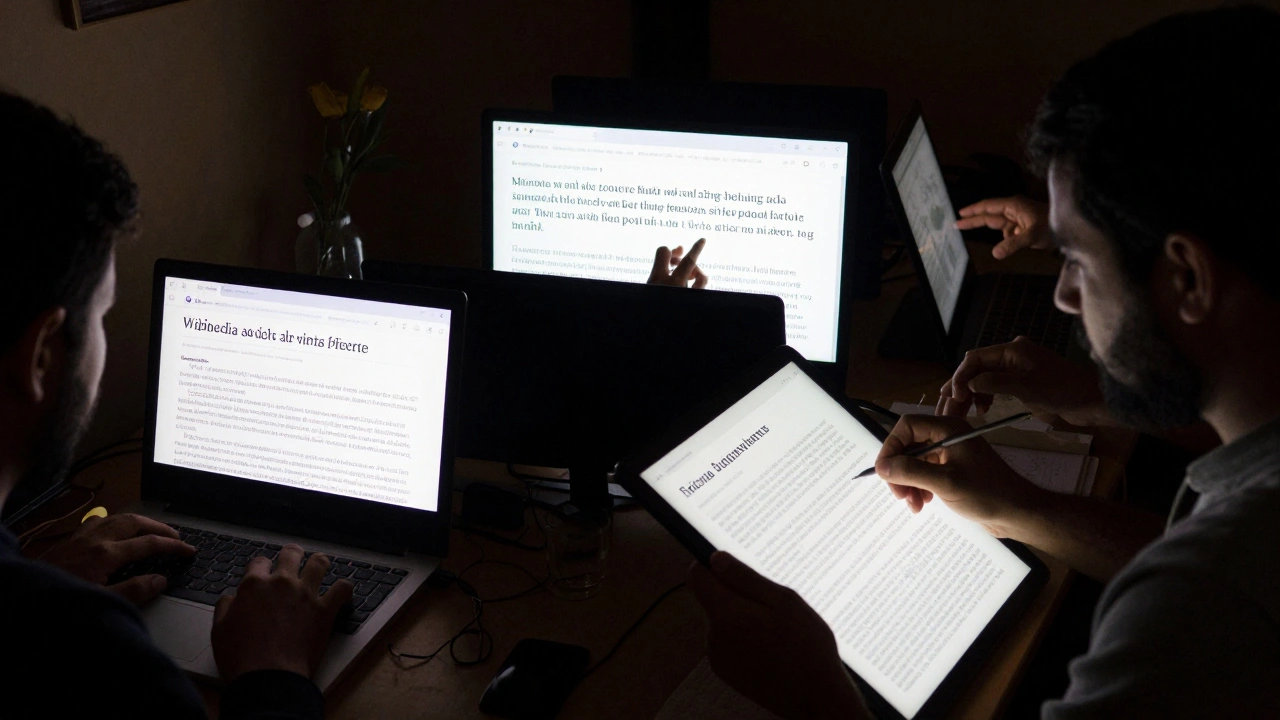

These differences aren’t just quirks-they affect how the world understands itself. If you’re researching climate change, you’ll get detailed, scientifically backed articles on English and German Wikipedia. But on Arabic or Russian versions, the same topic might be downplayed or omitted.

When students use Wikipedia for school projects, they often don’t realize they’re reading different realities. A student in Brazil might find a detailed article on indigenous land rights on Portuguese Wikipedia, while a student in Russia finds a one-paragraph summary that avoids mentioning government opposition.

Wikipedia presents itself as a single global knowledge base. But it’s really dozens of local knowledge bases, each shaped by language, law, culture, and fear.

What This Means for You

If you’re using Wikipedia for research, don’t just check one language. Compare versions. If you’re writing about a global topic, look at how it’s handled in at least three languages. You’ll often find missing context, hidden bias, or outright omissions.

For example, if you’re studying the history of colonialism, check the French, English, and Arabic versions. You’ll see different emphasis, different sources, and different silences. That’s not a flaw-it’s a mirror.

Wikipedia doesn’t give you truth. It gives you the truth as understood by the people who edit it. And those people are shaped by where they live, what they’re allowed to say, and what they’re afraid to say.