Every day, millions of students in rural villages, low-income cities, and conflict zones open a browser and find their textbook on Wikipedia. No subscription. No fee. No login. Just free knowledge. In places where schools lack books, libraries are closed, or teachers are scarce, Wikipedia isn’t just helpful-it’s often the only reliable source of structured learning available.

Wikipedia as a Public Library for the World

Wikipedia isn’t a traditional encyclopedia. It doesn’t sit on shelves. It doesn’t charge for access. It’s a living, constantly updated collection of over 60 million articles in more than 300 languages. And it’s accessible on any phone, even a basic Android model with slow internet. In Nigeria, a student studying for the WAEC exam might use Wikipedia to understand calculus concepts because their school has no math textbooks. In rural Bangladesh, a girl learning English finds grammar explanations in Bengali-translated Wikipedia pages. In Peru, a high schooler preparing for university entrance exams relies on Wikipedia’s summaries of Peruvian history because her local library hasn’t updated its materials since 2010.

Unlike paid platforms like Britannica or academic journals locked behind paywalls, Wikipedia doesn’t ask for money. It doesn’t require institutional access. It doesn’t discriminate based on income, location, or citizenship. That’s why UNESCO called it a ‘critical public good’ in its 2021 Global Education Monitoring Report. The report found that in 78% of low-income countries, Wikipedia is the most-used online educational resource among secondary students.

How It Works Where Schools Don’t

Education gaps aren’t just about missing buildings or teachers. They’re about missing information. A child in a refugee camp in Jordan might not have a science lab, but they can still learn how photosynthesis works through Wikipedia’s simple diagrams and step-by-step explanations. A teenager in the Democratic Republic of Congo might not have a physics teacher, but they can read about Newton’s laws in Swahili, with examples tied to local contexts like bicycle mechanics or market scales.

Wikipedia’s structure helps too. Articles are broken into clear sections: introduction, history, key concepts, examples, and references. You don’t need to read the whole thing to get the point. A student can jump straight to the ‘Applications’ section of ‘Electric Circuits’ and understand how it connects to their solar-powered phone charger. That’s the kind of flexibility no printed textbook offers.

And it’s updated fast. When the World Health Organization changed its guidelines on malaria prevention in 2024, Wikipedia editors updated the article within hours. Schools in Malawi, where textbooks take years to be printed and distributed, got the new info immediately.

Language Is the Biggest Barrier-Wikipedia Breaks It

Most educational content online is in English. But over 80% of the world’s population doesn’t speak English as a first language. That’s where Wikipedia’s multilingual model makes the difference.

There are now over 200 Wikipedia editions with more than 100,000 articles. The Hindi Wikipedia has 2.3 million articles. The Swahili edition has over 140,000-many written by volunteers in Tanzania and Kenya who translate science and history topics from English, then adapt them to local contexts. A student in Uganda learning about the solar system doesn’t have to struggle through English terms like ‘orbital eccentricity’-they can read it as ‘mikondo ya kikwetu’ with diagrams drawn by local contributors.

Even smaller languages matter. The Quechua Wikipedia, spoken by 8 million people in the Andes, has articles on agriculture, traditional medicine, and Inca history written in their own language. This isn’t just translation-it’s cultural preservation. Students aren’t just learning facts-they’re seeing their identity reflected in knowledge.

It’s Not Perfect, But It’s Reliable

People still say Wikipedia isn’t trustworthy. But research tells a different story. A 2023 study from Stanford University compared 1,200 Wikipedia articles on biology and history with peer-reviewed sources. They found that Wikipedia’s accuracy rate was 95% for basic facts, and 91% for complex concepts-comparable to commercial encyclopedias.

And here’s what most critics miss: Wikipedia’s transparency. Every edit is public. Every source is cited. If you see a claim like ‘The Amazon rainforest produces 20% of the world’s oxygen,’ you can click the citation and see the original journal paper. You can check who edited it and when. That’s more than you get from a textbook printed ten years ago with no way to verify its claims.

Wikipedia also has tools for students. The ‘Cite this page’ button gives you a formatted citation in APA, MLA, or Chicago style. The ‘Read in another language’ feature instantly translates pages using machine learning. And the mobile site loads in under 3 seconds on 2G networks.

Real Students, Real Impact

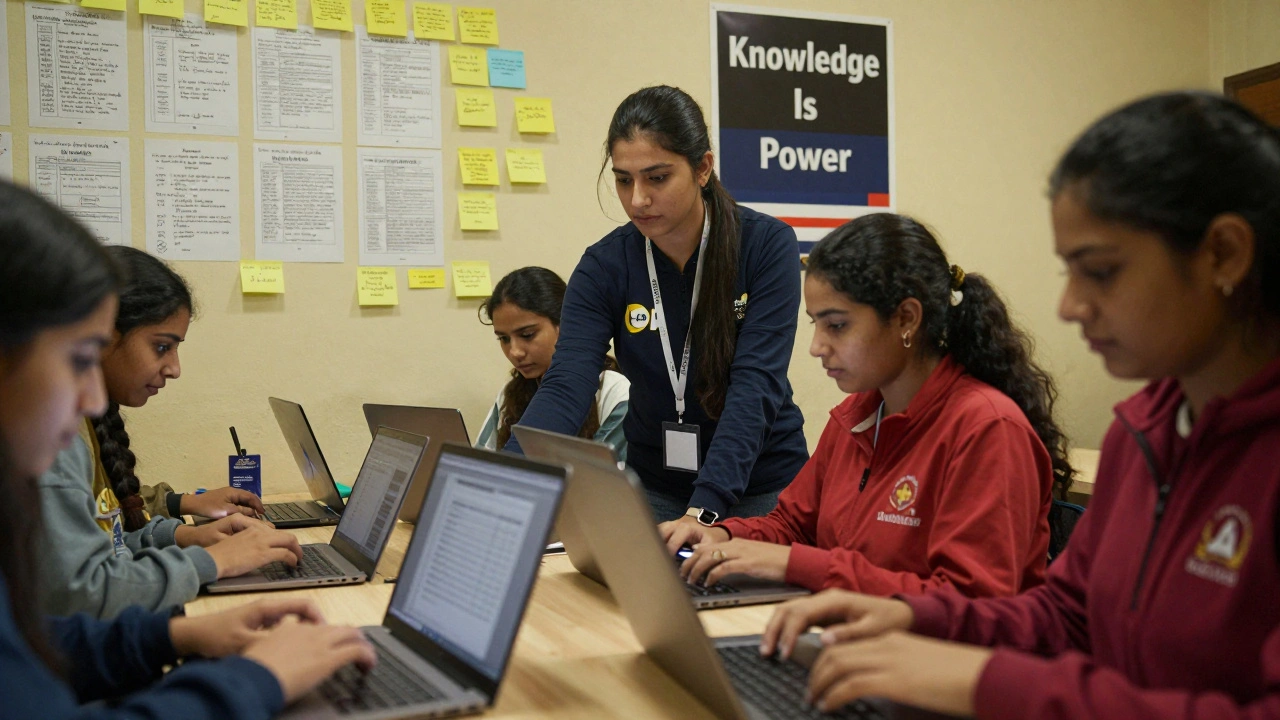

In 2024, a teacher in rural Nepal started a project where students used Wikipedia to create articles in Nepali about local plants, festivals, and traditional crafts. Within six months, those articles were being used by other schools. One student, 14-year-old Sunita, wrote about ‘Bhakta’-a medicinal herb used in her village. Her article got over 15,000 views in a year. She didn’t just learn biology-she became a knowledge creator.

At the University of Cape Town, a program called WikiStipend lets students earn credits for editing Wikipedia articles in African languages. Over 800 students have contributed since 2022. Their edits added over 5,000 new articles on South African history, medicine, and environmental science. Now, a student in Limpopo can search for ‘Zulu herbal remedies’ and find detailed, locally sourced information-not just a Google snippet from a foreign blog.

Who’s Behind This?

Wikipedia doesn’t run on corporate funding. It’s maintained by volunteers-teachers, nurses, engineers, high schoolers, retirees. In India, retired professors spend their evenings correcting science articles. In Colombia, university students organize edit-a-thons in community centers. In Pakistan, women’s groups train girls to edit Wikipedia in Urdu and Sindhi.

The Wikimedia Foundation, which hosts Wikipedia, doesn’t sell ads or data. It survives on small donations from millions of people worldwide. That’s why it can stay free. That’s why it’s not owned by any government, corporation, or political group.

This isn’t charity. It’s infrastructure. Like roads or electricity, Wikipedia is a public good that keeps society running. And in places where governments can’t or won’t provide education, it fills the gap.

What’s Missing? And What’s Next

Wikipedia still has gaps. Articles on indigenous knowledge, local history, and women’s contributions in many regions are underrepresented. Some languages still have fewer than 10,000 articles. And not everyone has a phone or internet-yet.

But efforts are growing. The Wikimedia Foundation now partners with libraries in Rwanda and Cambodia to offer offline Wikipedia via USB drives and solar-powered tablets. In Bolivia, community radio stations read Wikipedia articles aloud for people without internet. In Haiti, volunteers print Wikipedia pages on recycled paper and distribute them in schools.

Wikipedia won’t replace teachers. It won’t replace labs or classrooms. But it can give every student, no matter where they live, the chance to learn. And that’s not just access-it’s equity.

Is Wikipedia really accurate enough for students to use?

Yes, for most educational purposes. Studies from Stanford, the University of Oxford, and UNESCO have found Wikipedia’s accuracy matches or exceeds traditional encyclopedias on basic and intermediate topics. The key is using it as a starting point-check the citations, compare with other sources, and avoid memorizing claims without verifying them. It’s not perfect, but it’s transparent, which makes it more trustworthy than many closed-source textbooks.

Can students cite Wikipedia in academic papers?

Most universities discourage citing Wikipedia directly because it’s a secondary source. But students can-and should-use it to find original sources. Every Wikipedia article lists references at the bottom. You can click those links to find peer-reviewed journals, books, or official reports, then cite those instead. Wikipedia is a map to reliable sources, not the destination.

Why doesn’t Wikipedia have more content in African and Indigenous languages?

The main reason is lack of contributors. Creating articles requires time, internet access, and digital literacy-all of which are unevenly distributed. But that’s changing. Groups like WikiAfrica and the Wikimedia Foundation are training local editors in over 40 countries. In 2024, the Yoruba Wikipedia grew by 300% thanks to university-led editing drives. The goal isn’t just to translate English content-it’s to build knowledge from local perspectives.

How can someone help improve Wikipedia for education?

Anyone can edit. Start by fixing a typo, adding a citation, or translating a short article into your language. If you’re a teacher, assign students to write or improve Wikipedia pages as part of a class project. Universities can partner with Wikimedia chapters to offer credit for contributions. Even sharing Wikipedia links with students in underserved areas helps. You don’t need to be an expert-just willing to help.

Does Wikipedia work without internet?

Yes, in limited ways. Projects like Kiwix and Offline Wikipedia allow users to download entire editions onto USB drives, SD cards, or tablets. Schools in remote areas of Nepal, Papua New Guinea, and the Sahel use these to store Wikipedia content and access it without internet. Some libraries in Kenya and Peru now lend out pre-loaded devices. It’s not perfect, but it’s a lifeline where connectivity is unreliable.