Every time you see a photo of a protest, a natural disaster, or a cultural festival on Wikipedia, there’s a story behind it. Not just the story in the image - but the story of how that image got there. That’s where photojournalism and Wikipedia Commons meet. It’s not just about uploading pictures. It’s about trust, ethics, and making sure the world’s knowledge isn’t just words - but also what we can see.

What Photojournalism Really Means in the Digital Age

Photojournalism isn’t just snapping pictures during big events. It’s telling truth through images. A photojournalist doesn’t just capture what’s happening - they decide what matters. They’re there when the power goes out in a refugee camp. They’re the ones holding their camera steady while the crowd shouts. Their work is raw, unfiltered, and often the only record of a moment that history might forget.

But here’s the catch: most of these images never make it into textbooks or news archives. They live online - on news sites, social media, or in private folders. That’s where Wikipedia Commons steps in. It’s not a gallery. It’s a public archive. And it needs images that are not just good - but legally free to use, accurately labeled, and ethically sourced.

Why Wikipedia Commons Isn’t Just Another Image Bank

Wikipedia Commons isn’t like Shutterstock or Getty Images. You can’t buy a license there. Everything uploaded must be under a free license - Creative Commons, public domain, or similar. That means the photographer gives up exclusive rights so anyone, anywhere, can use the image for education, research, or even commercial projects - as long as they credit the source.

Think about that. A photo taken in Ukraine in 2022, showing a child holding a stuffed animal amid rubble, was uploaded by a local journalist. Within days, it appeared in articles across 12 languages. No paywall. No subscription. Just access. That’s the power of Commons.

But here’s the problem: not every photojournalist understands how to license their work properly. Many assume that if they post it on Twitter or Instagram, it’s free to use. It’s not. And if someone uploads it to Commons without permission, it gets deleted - and the story behind it vanishes.

The Rules That Keep Commons Alive

Wikipedia Commons has strict rules - and they exist for a reason.

- Permission is mandatory. If you didn’t take the photo, you can’t upload it unless the original owner explicitly releases it under a free license.

- Context matters. A photo of a protest needs location, date, and description. Without it, it’s just a blurry face in a crowd.

- Don’t fake it. Manipulated images - even slight edits - are banned. If you darken shadows to make a building look more damaged, that’s not journalism. That’s misinformation.

- Attribution isn’t optional. You must credit the photographer and source. Even if the photo is public domain, you still have to say who took it.

These aren’t bureaucratic hoops. They’re what keep Wikipedia from becoming a graveyard of stolen photos and false narratives. In 2023, over 18,000 images were removed from Commons for copyright violations. That’s 18,000 stories that never got told because someone didn’t follow the rules.

How Photojournalists Can Help - Without Losing Control

Many photojournalists worry that uploading to Commons means losing control. That’s a myth.

You still own your copyright. You just choose to let others use your work under specific conditions. You can require attribution. You can forbid commercial use (though that’s rare on Commons). You can even specify that your image must not be altered.

Here’s how to do it right:

- Take your photo. Make sure it’s clear, well-composed, and tells a story.

- Write a detailed caption: location, date, subject, context. Who is in the photo? Why does it matter?

- Choose a license. CC0 (public domain) or CC BY-SA 4.0 (attribution required) are most common.

- Upload to Wikimedia Commons using their upload wizard.

- Tag it with relevant categories: Ukraine war, climate protest, refugee camp.

And here’s the secret: once it’s on Commons, your photo might be used in a textbook in Nairobi, a documentary in Tokyo, or a museum exhibit in Berlin. You won’t get paid. But you’ll have helped shape how the world remembers that moment.

Real Examples: When a Photo Changed How We See History

In 2020, a photo of a Black Lives Matter protest in Madison, Wisconsin, showed a young woman kneeling beside a police officer, holding a sign that read, “I am not your enemy.” The photographer, a local freelance journalist, uploaded it to Commons with full metadata. Within weeks, it appeared in articles about racial justice across Europe and Latin America.

Another example: in 2021, a Syrian refugee in Lebanon photographed her daughter’s first day of school - in a tent, with a chalkboard made of cardboard. That image is now used in UNICEF reports and UNESCO education guides. No one paid for it. But millions saw it.

These aren’t exceptions. They’re the rule. Commons has over 100 million files. About 12% are photos taken by professional photojournalists. That’s more than 12 million images of real human moments - free for the world to use.

The Ethical Tightrope: Consent, Privacy, and Harm

Just because you can upload a photo doesn’t mean you should.

What if the person in the photo is a child? A trauma survivor? A victim of violence? Publishing their image without consent can cause real harm - even if the photo is “newsworthy.”

Wikipedia Commons has a policy: if a person is identifiable and not a public figure, you need their permission to upload their image. That includes people in hospitals, refugee camps, or disaster zones. Even if they’re in the background. Even if you think they’re “just part of the scene.”

There are exceptions. Public figures - politicians, celebrities, activists - can be photographed in public without consent. But even then, context matters. A photo of a politician laughing at a rally is fine. A photo of them crying in a hospital room? That’s different.

And don’t forget: some cultures don’t believe in photographing the dead. Or the face of women. Or children. Ignoring that isn’t journalism. It’s disrespect.

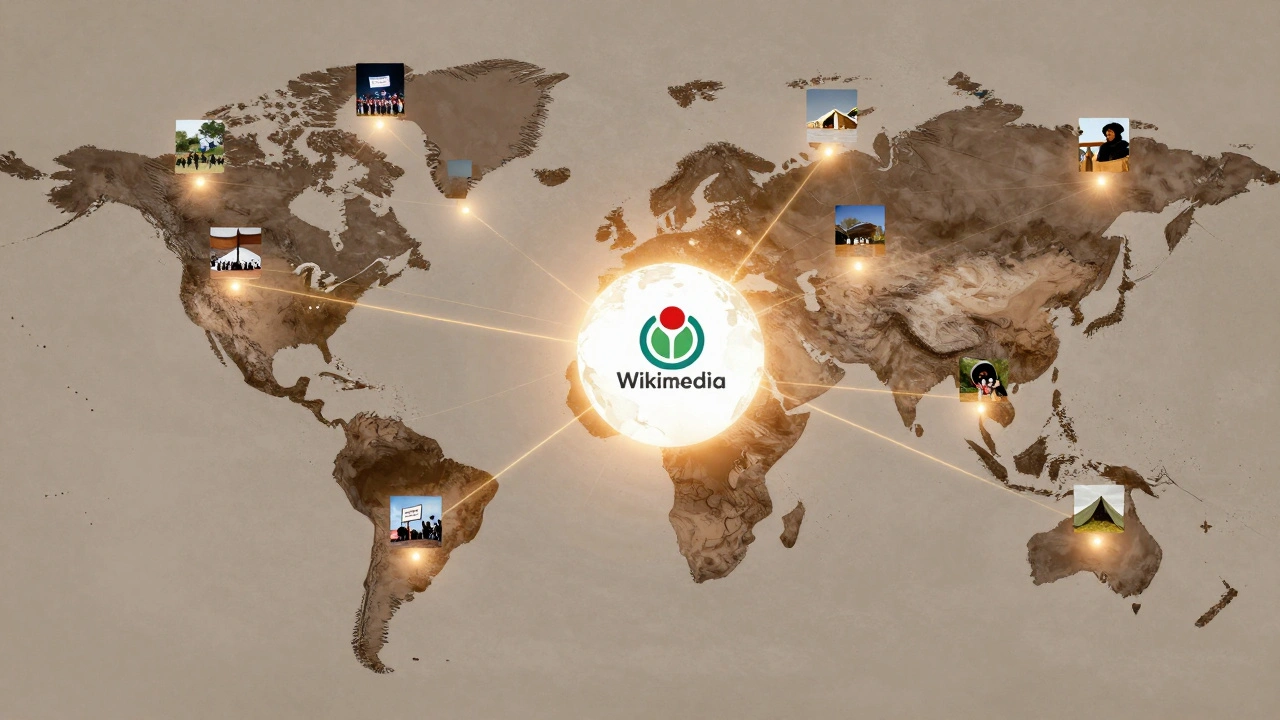

What Happens When Photojournalism and Wikipedia Collide

The result? A global visual archive unlike any other.

Unlike traditional news archives - locked behind paywalls or buried in newspaper morgues - Commons is open. It’s searchable. It’s editable. And it’s growing every day.

Researchers use it to track climate change. Teachers use it to show students what war looks like. Activists use it to prove human rights abuses. And photojournalists? They use it to make sure their work doesn’t disappear after the headlines fade.

There’s no other platform where a photo taken in Gaza, uploaded by a local journalist, ends up in a university lecture in Toronto - all without a single dollar changing hands.

How You Can Contribute - Even If You’re Not a Pro

You don’t need a press pass to help. If you’re at a community event, a local festival, or a climate march - take a photo. Write down the date and place. Ask permission if someone is clearly identifiable. Upload it to Commons with a clear caption.

Local history matters. A parade in Duluth. A protest in Omaha. A school opening in rural Alabama. These moments are rarely covered by national media. But they’re part of our collective memory. Commons is the only place where they can live forever - free and accessible.

And if you’re a student, a librarian, or a volunteer at a museum? Help tag old photos. Find out who took them. Check the license. Upload them. You’re not just organizing files. You’re preserving truth.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters Now

In 2026, misinformation spreads faster than ever. Deepfakes, AI-generated images, and manipulated videos are everywhere. People don’t know what’s real anymore.

Photojournalism - when done right - is one of the last defenses against that. And Wikipedia Commons is the only place where that defense is open to everyone.

It’s not perfect. There are mistakes. There are bad uploads. But the system works because it’s transparent. Every edit is recorded. Every source is traceable. Every photo can be challenged.

That’s why, when the next big event happens - whether it’s a flood, a strike, or a revolution - the world will look to Commons first. Not because it’s the most glamorous. But because it’s the most honest.

So the next time you see a photo on Wikipedia - don’t just scroll past it. Ask: Who took this? Why was it uploaded? And what story is it trying to tell?

Can I use photos from Wikipedia Commons for commercial projects?

Yes, most photos on Wikimedia Commons can be used commercially - as long as you follow the license. The most common license, CC BY-SA 4.0, requires you to give credit to the photographer and share any derivative work under the same license. Always check the specific license on the image’s page before using it.

What if I find a photo on Instagram and want to upload it to Commons?

Don’t. Just because an image is on social media doesn’t mean it’s free to use. Instagram’s terms don’t give you permission to republish someone else’s photo. Uploading it to Commons without the original owner’s consent will result in deletion - and could lead to legal issues. Always contact the photographer directly and ask for written permission under a free license.

Do I need to be a professional photographer to upload to Commons?

No. Anyone can upload - students, volunteers, amateur photographers, and community members. What matters is that the photo is original, well-documented, and legally licensed. A photo of your local library’s renovation, if properly labeled, is just as valuable as a photo from a war zone.

How do I know if a photo on Commons is trustworthy?

Check the upload details. Look for the photographer’s name, the date and location, and the license type. Trusted sources often include news organizations like Associated Press or Reuters (if they’ve released the image under a free license). Also, look at the image’s talk page - other users may have flagged issues or added context. Avoid images with vague captions or no source.

Why doesn’t Wikipedia just use stock photos instead?

Stock photos are generic. They don’t show real people, real places, or real events. Wikipedia aims to document reality - not staged scenes. A photo of a real refugee camp in Jordan tells a different story than a stock image of a smiling family on a beach. Commons exists to preserve authentic visual history - not replace it with illusions.