Ever read an article that felt like half a story? You get the basic idea, but then it stops. No examples. No sources. No depth. Just a sentence or two. That’s a stub. And they’re everywhere - especially in community-driven knowledge bases like Wikipedia, Wiktionary, and smaller niche wikis. Stubs aren’t always bad. Sometimes they’re starting points. But when they stay that way for years, they hurt the whole system.

What Makes an Article a Stub?

A stub isn’t just short. It’s incomplete in a way that stops you from learning anything real. Think of it like a building with only the foundation laid. You know what it’s supposed to be, but you can’t live in it.

Here’s what turns a brief article into a true stub:

- No citations - claims are made but not backed up

- No context - you don’t learn why this topic matters

- No examples - abstract ideas aren’t grounded in reality

- No structure - no clear sections, no logical flow

- No links - no way to explore related topics

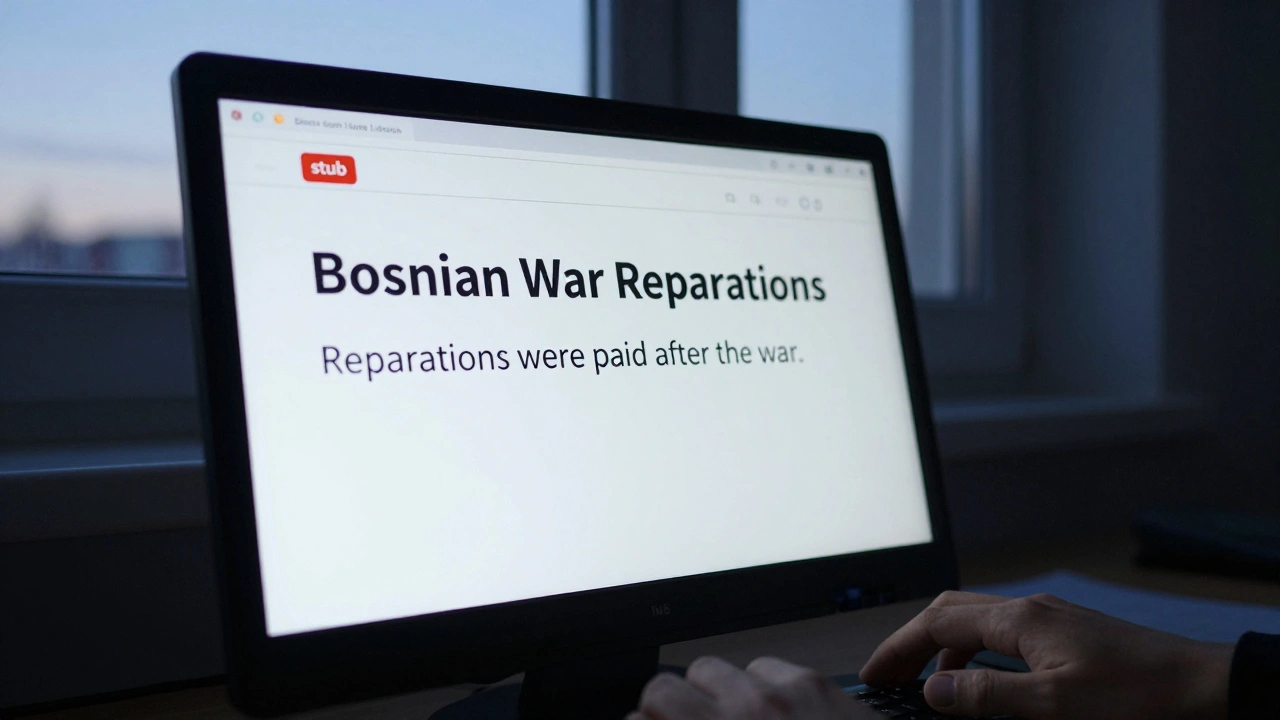

Take the article on “Bosnian War reparations”. If it says, “Reparations were paid after the war,” that’s a stub. But if it explains how much was paid, by whom, to whom, over what timeline, and what legal frameworks were used - now it’s useful. The difference isn’t word count. It’s usefulness.

Why Do Stubs Persist?

You’d think someone would fix them. But here’s the reality:

- It’s invisible work. No one gets praised for expanding a stub. You don’t get likes, shares, or badges.

- It’s hard to start. If you don’t know much about the topic, you don’t know where to begin. Research feels overwhelming.

- It’s boring. Editing a 3-line entry isn’t exciting. People want to write about new trends, not fill gaps.

- It’s assumed someone else will do it. The “bystander effect” applies to knowledge too.

Wikipedia’s own data shows that over 10% of its English articles are classified as “stubs” - and many of those haven’t been touched in 5+ years. Some were created in 2007 and never updated. That’s not a feature. That’s a flaw.

How to Spot a Stub That Needs Work

Not every short article is a stub. A well-written 200-word summary of a complex idea can be perfect. So how do you tell the difference?

Ask yourself:

- Does this article answer the most obvious follow-up questions?

- Could someone walk away thinking they understand it - but actually be completely wrong?

- Is there a single sentence that feels like it’s missing context?

- Are there any bolded terms that aren’t linked to their own articles?

- Is there a citation? If yes, is it a reliable source? If no, is it a claim that needs one?

Here’s a real example from a public wiki: “The Kalinga Prize is awarded by UNESCO.” That’s it. One sentence. Who gets it? When? How many people have won? What’s the prize? Why does it exist? That’s not a summary. That’s a placeholder.

How to Improve a Stub

Improving a stub doesn’t require being an expert. It just requires curiosity and a little time.

Here’s a simple 5-step process:

- Read the stub and write down every question it leaves unanswered.

- Find one reliable source - a book, academic paper, official report, or trusted news outlet.

- Add one new fact - even if it’s just one sentence. “The prize is awarded annually to individuals who promote science communication.”

- Link to related articles - if the stub mentions “UNESCO,” link to its main page. If it mentions “science communication,” link to that topic if it exists.

- Tag it - use a “stub” template or category so others know it’s a work in progress.

You don’t need to fix everything. Just make it better than it was. One person adding one fact is still progress.

What Happens When Stubs Are Fixed?

When stubs get expanded, the whole knowledge base improves.

Take the article on “Lithium-ion battery recycling”. In 2020, it was a two-line stub. By 2023, after dozens of small edits, it had:

- A breakdown of recycling methods

- Stats on recovery rates in the U.S. vs. EU

- Links to major companies doing it

- Regulatory differences between states

- A section on environmental risks

That article went from being ignored to being cited in university papers and government reports. That’s the ripple effect.

Every time you improve a stub, you’re not just helping one reader. You’re making the entire system more trustworthy. People start relying on it. They stop saying, “I’ll just Google it.” They say, “I’ll check the wiki first.”

Tools That Help You Find Stubs

You don’t have to guess which articles need work. There are tools built for this.

- Wikipedia’s Stub Sorter - lets you browse stubs by category (e.g., “Biology stubs,” “History stubs”).

- WikiProject pages - many communities track their own stubs. For example, WikiProject Medicine has a list of over 15,000 medical stubs needing expansion.

- Special:Shortpages - shows the shortest articles on Wikipedia. Filter by creation date to find old, untouched ones.

- WikiWho - shows who edited what and when. If an article hasn’t been touched since 2012, it’s a good candidate.

You can start with just 10 minutes. Go to Special:Shortpages. Pick an article that looks interesting. Add one sentence. That’s it.

Why This Matters for Everyone

Stubs aren’t just a wiki problem. They’re a reflection of how we value knowledge.

When we let stubs stay broken, we send a message: “It’s okay if information is incomplete.” That’s dangerous. In a world full of misinformation, the opposite needs to be true: “If you don’t know it fully, don’t say it at all.”

Fixing a stub is a quiet act of integrity. It says: I care enough to make sure this is right.

And it’s not just about accuracy. It’s about accessibility. A well-written article helps someone in rural India, a student in South Sudan, or a retiree in Wisconsin understand something important. But only if it’s complete.

You don’t need to be a scholar. You don’t need to write a thesis. Just find one stub. Expand it by one fact. Link one term. Add one source. That’s enough.

The next time you read something that feels half-finished - don’t just scroll past. Fix it. Someone else will thank you for it.

What’s the difference between a stub and a short article?

A short article can be complete and useful even if brief - think of a concise summary of a complex idea. A stub is incomplete by design. It lacks context, sources, examples, or structure. It leaves more questions than answers. A short article answers the core question; a stub only hints at it.

Can I edit stubs even if I’m not an expert?

Yes. You don’t need to be an expert to improve a stub. You just need to be curious. Find one reliable source - a government report, a university page, a reputable news outlet - and add one clear fact. That’s enough to turn a placeholder into something useful. Many of the best edits come from non-experts who ask, “Wait, what does this mean?”

Why don’t more people fix stubs?

Because it’s invisible work. No one sees it. No one praises it. It doesn’t get likes, shares, or viral attention. People are drawn to writing about new trends, not filling gaps. But that’s exactly why stubs need more attention - they’re the quiet foundation of reliable knowledge.

Are stubs harmful?

Yes, when they’re left unaddressed. They give false confidence - users think they’ve found complete information when they haven’t. Over time, this erodes trust in the entire knowledge source. A single stub can mislead thousands if it’s the top result in a search. That’s why fixing them isn’t optional - it’s essential.

How long should an article be to avoid being a stub?

There’s no magic number. A 300-word article can still be a stub if it lacks sources, examples, or context. A 1,200-word article can be excellent if it answers the key questions. Focus on completeness, not length. Ask: Would someone walk away understanding the topic - not just knowing its name?