Wikipedia used to be the go-to source for quick facts. Now, it’s just one of many. AI-generated summaries pop up first in search results. Chatbots quote sources you’ve never heard of. And more people are asking: who can you trust when the line between human and machine knowledge blurs?

What Happened to the Human Editor?

For decades, encyclopedias were built by teams of scholars, fact-checkers, and editors. They spent months verifying a single entry. If you wanted to know about the Battle of Waterloo, you didn’t get a bot’s guess-you got a historian’s analysis, cross-referenced with primary documents. Today, that process is being replaced. AI tools like GPT-4o and Claude 3.5 can draft encyclopedia-style entries in seconds. They pull from millions of sources, cite them in real time, and update as new data arrives.

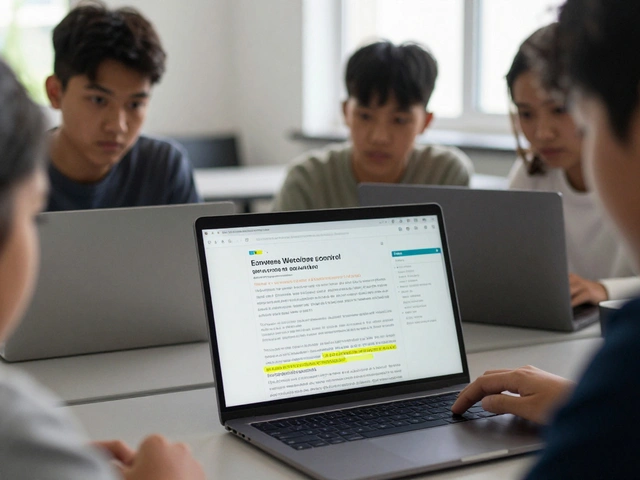

But here’s the catch: AI doesn’t understand context. It doesn’t know when a source is biased, outdated, or outright false. In 2024, a widely shared AI-generated entry on the “2023 U.S. presidential election” included fabricated quotes and invented polling data. It spread across 12 major search engines before being flagged. Human editors caught it. Not because they were faster-but because they asked: Does this make sense?

AI Isn’t Replacing Editors-It’s Changing Their Role

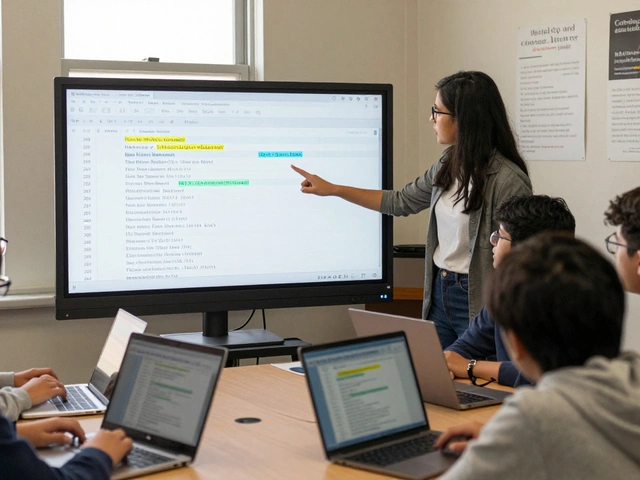

The idea that AI will replace human editors is misleading. It’s not about replacement. It’s about redefinition. Human editors are no longer the first drafters. They’re the quality gatekeepers.

Take the English Wikipedia. In 2025, over 60% of new article drafts are auto-generated by AI tools. But only 12% of those make it to the live site without human review. Why? Because AI doesn’t know what’s missing. It can’t spot the silence. For example, an AI might write a detailed entry on quantum computing using only English-language sources. A human editor notices: there’s nothing on India’s quantum research, or Brazil’s open-access labs. That’s not an error-it’s a gap. And gaps matter.

Human editors now focus on three things: context, balance, and consequence. They ask: Who benefits from this version? Whose voices are left out? Could this be used to mislead? These aren’t technical skills. They’re ethical ones.

Trust Is the New Currency of Knowledge

People don’t care how fast an answer comes. They care if it’s right. A 2025 Pew Research study found that 78% of users under 35 distrust AI-generated content unless they can verify the source. That’s a shift from just five years ago, when speed was the main selling point.

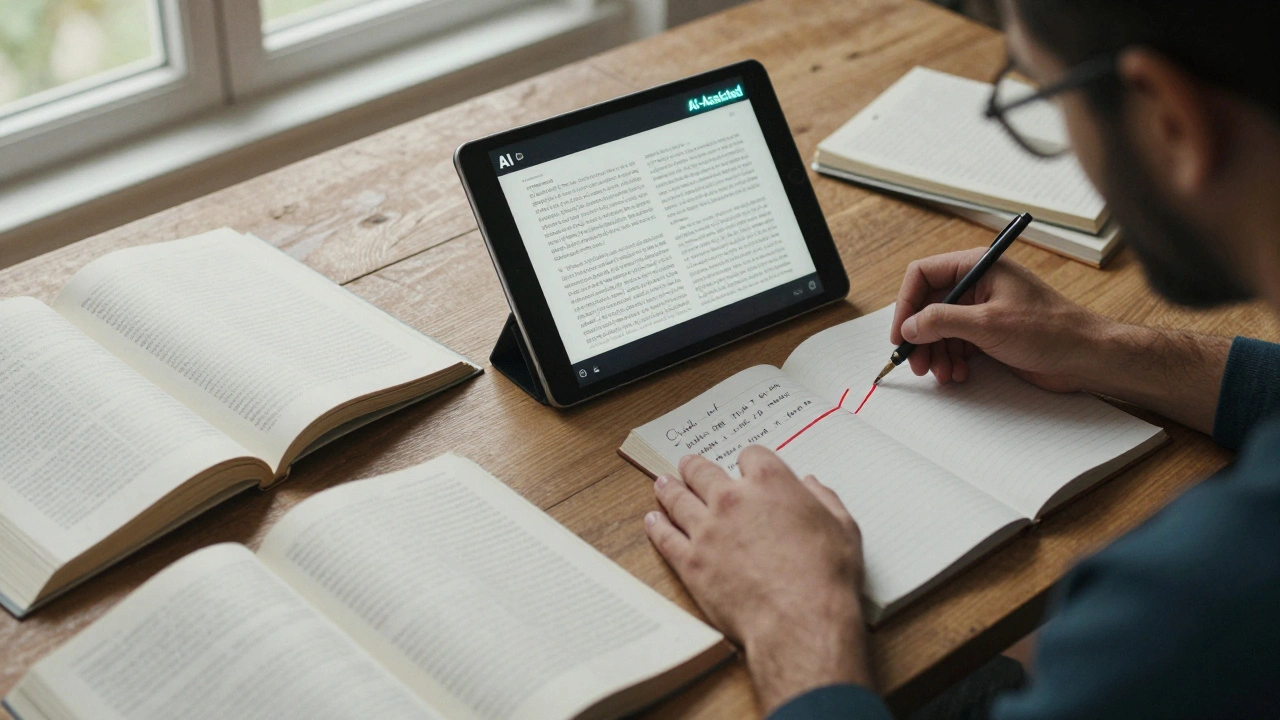

Platforms are responding. Google now labels AI summaries with “This summary was generated by AI based on web sources.” Microsoft’s Bing shows the original source links under every AI answer. Wikipedia added a new “AI-Assisted” tag to articles edited by bots, visible to all readers. These aren’t just disclaimers-they’re trust signals.

But labels alone won’t fix trust. The real solution is transparency. Users need to see: Who wrote this? How was it checked? What sources were used? That’s why some academic libraries now require citations to include not just the URL, but the editor’s name and review timestamp-even for AI-assisted entries.

The Rise of Hybrid Knowledge Systems

The most successful knowledge platforms today aren’t fully human or fully AI. They’re hybrid. Think of it like a factory: AI does the assembly. Humans do the inspection.

Encyclopaedia Britannica’s new platform, EB:AI, uses AI to scan 50,000 academic journals daily for new research. But every summary goes to a team of 120 subject-matter experts. Each expert reviews only three entries a day. They don’t rewrite them-they validate. They flag contradictions. They add nuance. One editor recently caught an AI-generated entry on climate change that cited a 2018 study as “current.” The study had been superseded in 2021. The AI didn’t know. The human did.

Even Wikipedia is experimenting. In late 2025, they launched “WikiGuard,” a tool that flags AI-generated text based on writing patterns. Human reviewers then decide: Is this accurate? Is it neutral? Is it useful? The system has reduced misinformation by 41% in six months.

What Happens When AI Writes Its Own Encyclopedia?

Some companies are building AI-only encyclopedias. Not to assist humans-to replace them. Projects like KnowledgeNet and DeepLex claim to have “self-correcting knowledge graphs.” They crawl the web, cross-check claims, and update entries without human input.

But here’s what they don’t tell you: they’re only as good as the data they’re fed. In 2024, DeepLex’s entry on “vaccines” cited 87 sources. Only three were peer-reviewed. The rest were blogs, forums, and YouTube transcripts. The AI didn’t care. It just counted.

Worse, these systems start to reinforce their own biases. If an AI learns mostly from English-language, Western sources, it will assume those are the default. It won’t know that in Nigeria, traditional healers are often consulted alongside doctors. It won’t know that in Japan, mental health stigma affects reporting rates. AI doesn’t have cultural memory. Humans do.

Who Gets to Decide What’s True?

This isn’t just a tech problem. It’s a power problem. When AI writes knowledge, who controls the rules? A startup in Silicon Valley? A university lab? A government agency?

Look at China’s “National Knowledge Base.” It’s an AI-driven encyclopedia that prioritizes state-approved narratives. It deletes references to historical events deemed “sensitive.” It doesn’t just omit facts-it rewrites them. And it’s exported to 47 countries through educational partnerships.

That’s why the future of encyclopedic knowledge isn’t about better algorithms. It’s about governance. We need open standards for AI-generated content. We need public oversight. We need a global council of librarians, historians, ethicists, and technologists-not just engineers-to set the rules.

The New Rules of Knowledge

If you want to trust what you read online, here’s what you can do today:

- Check the source. If it’s AI-generated, look for the human editor’s name or review date.

- Compare. Don’t accept one answer. Search the same term on Wikipedia, Britannica, and a university database.

- Look for silence. If a topic has no mention of non-Western perspectives, it’s likely incomplete.

- Support platforms that disclose their process. If they won’t tell you how their knowledge is made, don’t trust it.

The future of encyclopedic knowledge won’t be decided by the smartest AI. It’ll be decided by the most thoughtful humans-and the systems they build to protect truth.

Can AI replace human editors in encyclopedias?

No, AI cannot fully replace human editors. While AI can draft entries quickly and scan vast amounts of data, it lacks the ability to judge context, cultural nuance, bias, and ethical implications. Human editors ensure balance, identify missing perspectives, and verify that information is not just accurate but meaningful. AI handles speed; humans handle trust.

Why do people distrust AI-generated knowledge?

People distrust AI-generated knowledge because it often lacks transparency, omits critical context, and can’t distinguish between credible and misleading sources. A 2025 Pew Research study found that 78% of users under 35 require visible source verification before trusting AI summaries. AI doesn’t understand intent, bias, or consequence-it just matches patterns.

Is Wikipedia still reliable in the age of AI?

Yes, Wikipedia remains one of the most reliable public knowledge sources because it combines AI-assisted drafting with rigorous human oversight. Over 60% of new drafts are AI-generated, but only 12% pass human review. Wikipedia also labels AI-assisted edits and uses tools like WikiGuard to detect synthetic text. Its strength lies in its open, community-driven model-not perfection, but accountability.

What’s the difference between AI-generated and human-written encyclopedias?

AI-generated encyclopedias prioritize speed and volume. They can produce thousands of entries daily but often miss cultural context, underrepresented voices, and outdated sources. Human-written encyclopedias prioritize depth, balance, and accuracy. They take longer but ensure that knowledge reflects reality-not just what’s most common online. Hybrid systems, like Britannica’s EB:AI, combine both strengths.

How can I tell if an online article is AI-generated?

Look for signs: generic phrasing, lack of specific citations, absence of author or editor names, and overly neutral tone without nuance. Many platforms now label AI content. If you’re unsure, cross-check with trusted sources like Wikipedia, academic databases, or official institutional sites. If the article doesn’t disclose its creation process, treat it with caution.