Wikipedia doesn’t look like a tech company. No flashy ads, no push notifications, no dark mode toggle you have to hunt for. But behind the plain white pages and simple blue links, there’s a quiet, powerful system running: UI A/B testing. Every small change-moving the search bar, changing button colors, tweaking how citations appear-is tested on real users before it goes live. This isn’t about increasing clicks or ad revenue. It’s about making sure millions of people can find, read, and edit information without confusion.

How Wikipedia Tests Changes Without Disrupting Readers

Wikipedia’s A/B tests are run by the Wikimedia Foundation’s Design and Research team. They don’t test big overhauls. They test tiny things: Is a slightly darker link easier to click? Does moving the edit button from the top to the side reduce accidental edits? These tests run on a small percentage of users-sometimes just 1%-and only for a few days.

For example, in 2021, Wikipedia tested changing the color of the "Edit" button from green to blue. Green had been used for decades, but data showed users with color vision deficiencies often missed it. The blue version was tested on 50,000 users. The result? Click-through rates for editing increased by 8.7% among users with color vision issues. The change rolled out globally.

Tests are never done on live editing pages unless absolutely necessary. Instead, they use "beta features"-optional settings users can turn on. If you’ve ever seen a banner saying "Try the new edit interface," you’ve been part of a test. No one is forced into it. And if a test shows a feature makes things worse, it gets scrapped. No exceptions.

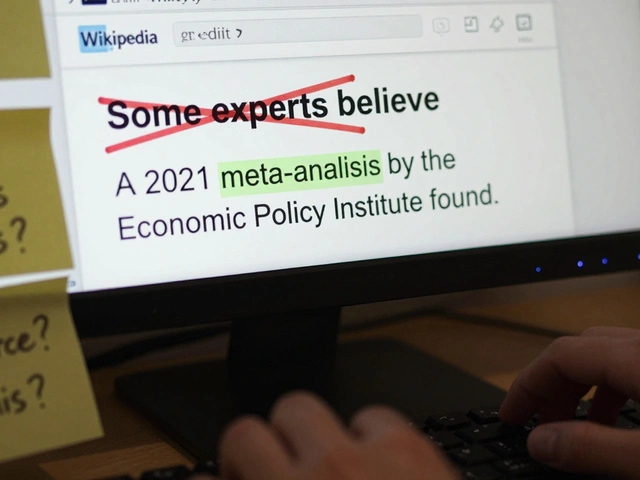

Why Wikipedia Doesn’t Test for Engagement Like Social Media

Most tech companies A/B test to maximize time-on-site, clicks, or sign-ups. Wikipedia tests to reduce friction. The goal isn’t to keep you scrolling-it’s to help you leave faster, with the right information.

A 2020 test looked at whether adding a "Quick Facts" box above articles improved reading speed. The team expected it to help. Instead, users spent 12% longer on the page and were more likely to get lost in the summary. The box was removed. Why? Because Wikipedia’s mission isn’t to entertain-it’s to inform. If a change makes people linger longer but understand less, it fails.

Wikipedia’s metrics are different: edit success rate, citation accuracy, page load time, and whether users return to fix errors they spotted. If a UI change makes it harder for someone to fix a typo, it’s rejected-even if it looks "prettier."

The Ethics of Testing on a Public Knowledge Project

Here’s the big question: Is it okay to experiment on people who use Wikipedia to find medical advice, school research, or emergency info?

Wikipedia has strict ethical guidelines. All tests must pass review by an internal ethics board. Key rules:

- No testing on sensitive topics: medical, legal, political, or religious content is off-limits for UI changes.

- No data collection on users’ edit history or personal info.

- No changes that could influence opinions, beliefs, or behavior.

- Users must be able to opt out easily.

- All test results are published publicly.

In 2019, a team proposed testing whether changing the wording of a warning message ("This page may be outdated") would make users more likely to check the talk page. The board rejected it. Why? Because altering language around accuracy could unintentionally affect how users perceive truth. Even a small word change could have ripple effects.

Wikipedia doesn’t treat users as data points. They’re contributors, researchers, and sometimes people in crisis. The team remembers that every test is happening on a site where someone might be reading about cancer treatment at 2 a.m.

How Volunteers Are Involved in Testing

Wikipedia isn’t just run by engineers. Over 100,000 active editors help test new interfaces. The Wikimedia Foundation runs a volunteer user testing program called "Wikipedia Editors as Researchers." Contributors sign up to try beta features and give feedback in plain language.

One volunteer, a retired teacher from Ontario, tested a new citation tool for three months. She pointed out that the tool assumed users knew how to format journal titles-something many older editors didn’t. The team simplified the prompts and added examples. That change helped thousands of non-expert editors.

Volunteers aren’t just testers-they’re co-designers. Their feedback often leads to features that engineers never thought of. A simple request from a high school student in Nigeria led to a new mobile feature: the ability to save edits as drafts without logging in. That feature is now used by over 2 million people monthly.

What Happens When a Test Goes Wrong?

Even with safeguards, mistakes happen. In 2022, a test changed the layout of the mobile edit screen to make the "Save" button bigger. Sounds good, right? But the new layout accidentally hid the "Preview" button under a collapsible menu. Hundreds of users saved incomplete edits without seeing them first.

The issue was caught within 11 hours by a volunteer who noticed a spike in broken citations. The team rolled back the change immediately and published a public post explaining what happened. They didn’t hide it. They apologized. And they added a new rule: any test affecting the edit interface must include a mandatory preview step.

Wikipedia’s culture values transparency over perfection. When something breaks, they fix it fast-and tell everyone how it happened.

What You Can Learn From Wikipedia’s Approach

You don’t run a global encyclopedia, but you can borrow its principles:

- Test small. Don’t overhaul everything at once.

- Measure the right things. If your goal is clarity, don’t track clicks.

- Protect users from harm. If your product helps people make decisions, don’t test language that could mislead.

- Listen to real users-not just analytics. A single voice can reveal a flaw no dashboard shows.

- Be public about your tests. Transparency builds trust.

Wikipedia proves you don’t need a billion-dollar budget to do ethical, effective UI testing. You just need to care more about the user than the interface.

Is Wikipedia allowed to run A/B tests on its users?

Yes, but under strict ethical rules. Wikipedia only tests minor interface changes, never content or wording that could influence beliefs. All tests are opt-in, limited to small user groups, and reviewed by an internal ethics board. Results are published publicly, and users can opt out at any time.

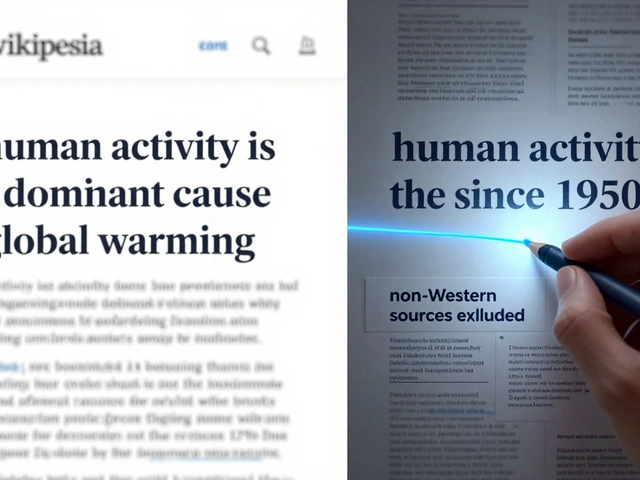

Do A/B tests on Wikipedia affect the accuracy of information?

No. UI tests only change how things look or work, not what’s written on the page. The content is edited by volunteers and governed by strict sourcing policies. Even if a button moves, the facts stay the same. Tests are never run on articles about health, politics, or religion where wording could influence perception.

How can I participate in Wikipedia UI testing?

You can join the "Wikipedia Editors as Researchers" program by signing up on the Wikimedia Foundation’s website. Once accepted, you’ll get invitations to test new features, give feedback, and even help design tools. No technical skills are needed-just regular editing experience and honest opinions.

Why doesn’t Wikipedia use A/B testing like Facebook or Google?

Because their goals are different. Facebook tests to keep you scrolling. Google tests to show you more ads. Wikipedia tests to help you find the truth faster and edit more accurately. It doesn’t track your behavior for profit. It tracks how well you can use the site to do your work-whether that’s writing a paper, checking a fact, or fixing a typo.

Are Wikipedia’s UI changes permanent?

Not always. Many changes are tested for weeks or months, then rolled back if they don’t improve the experience. Even popular features like the mobile editor were tested for over a year before becoming the default. If a change doesn’t help users, it gets removed-even if it looks modern or trendy.

What’s Next for Wikipedia’s Interface?

Right now, the team is testing ways to make citation tools easier for non-experts. They’re also exploring voice navigation for users with visual impairments. And they’re building a new dashboard so editors can see how their changes affect readers-without compromising privacy.

One thing won’t change: Wikipedia’s commitment to doing things right, not just fast. In a world where every click is monetized, it’s rare to see a platform that still asks: "Does this help the user?" And not just the user who clicks the most-but the one who needs the truth the most.