Wikipedia runs on a system that handles over 20 billion page views a month. That’s not just a website - it’s one of the largest, most complex open-source platforms in the world. And behind it? A small, quiet team of engineers at the Wikimedia Foundation who keep it all running - without ads, without paywalls, and without corporate backing. Their infrastructure isn’t built for profit. It’s built for access.

How Wikipedia’s Infrastructure Works

Most websites use cloud services like AWS or Google Cloud. Wikipedia doesn’t. It runs on its own global network of servers, mostly located in data centers in the U.S., Europe, and Asia. These aren’t rented virtual machines. They’re physical hardware, carefully chosen and maintained by the foundation’s infrastructure team. Why? Because renting cloud services at Wikipedia’s scale would cost hundreds of millions a year. Instead, they partner with organizations like the Internet Archive and universities to get discounted or donated hardware and bandwidth.

The core of Wikipedia’s backend is MediaWiki - the open-source software that powers all Wikimedia projects. It’s not some polished commercial product. It’s a 20-year-old codebase, written mostly in PHP, with over 1.5 million lines of code. It’s been patched, refactored, and rebuilt so many times that it’s a living museum of web development history. But it works. It handles edits from millions of users every day, even during traffic spikes like election nights or breaking news events.

Every edit, every image upload, every search query gets routed through a complex stack: load balancers, caching layers (Varnish and Redis), database clusters (MariaDB), and content delivery networks. The team uses Kubernetes to manage containers, but they avoid over-automation. They’ve learned that simplicity beats complexity when you’re trying to keep a site alive with a team of 40 engineers.

Development Philosophy: Slow, Stable, Transparent

Most tech companies move fast and break things. Wikimedia moves slow - and breaks nothing. Their development philosophy is built on three rules: stability first, transparency always, and community above all.

There’s no sprint cycle. No quarterly product launches. Instead, every feature goes through public discussion on Phabricator, their open issue tracker. Volunteers, editors, and developers debate every change. A simple UI tweak might take six months to get approved. That’s because one wrong change can break editing for half a million active contributors worldwide.

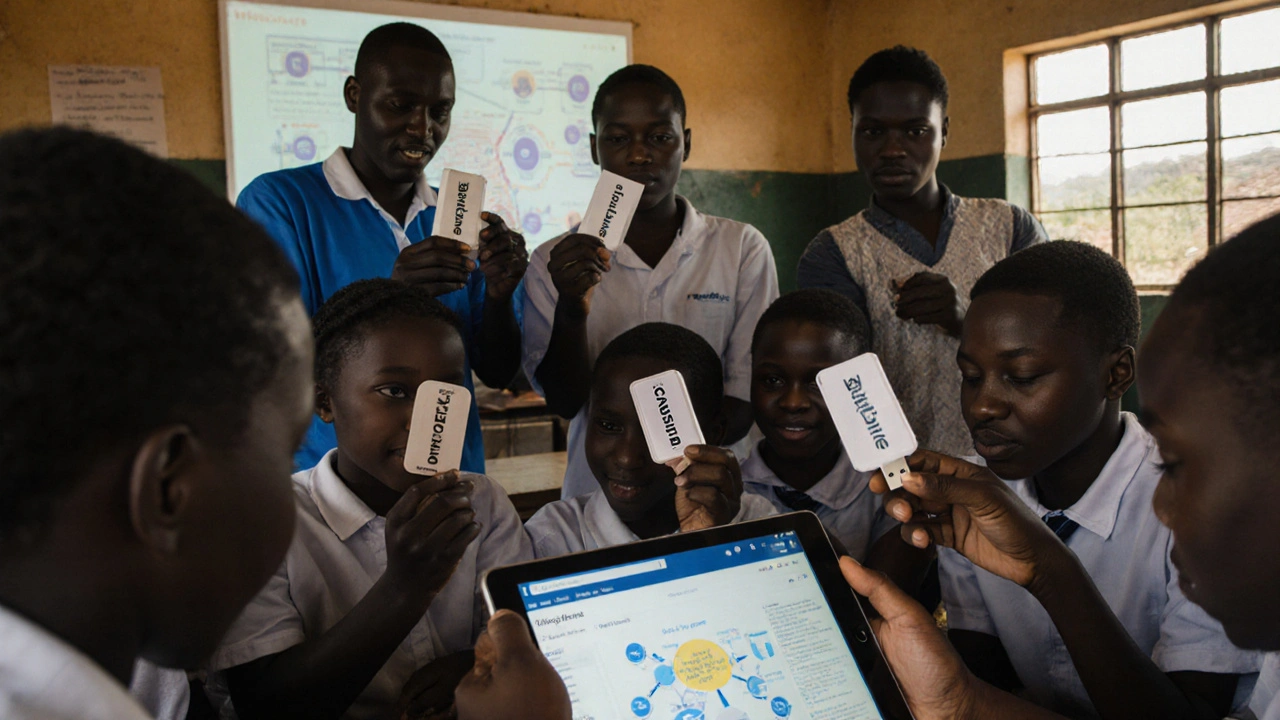

They don’t use A/B testing like Facebook or Google. Why? Because they can’t risk biasing user behavior. Instead, they rely on feedback from real editors. If a new edit interface confuses a veteran contributor from Indonesia or Nigeria, it gets redesigned. The team doesn’t just listen - they embed themselves in community forums, attend edit-a-thons, and even travel to places like Lagos and Manila to meet contributors in person.

One of their biggest wins was the VisualEditor project. Launched in 2013, it let people edit Wikipedia without learning wiki markup. It took five years of testing, feedback, and iteration. Today, over 70% of new editors use it. But the team didn’t rush it. They waited until it worked reliably on mobile, on slow connections, and in languages with non-Latin scripts.

Scaling Without Money

Wikimedia’s annual budget is around $150 million. That sounds like a lot - until you realize that Google’s engineering team alone spends more than that every week. The tech team operates on a fraction of that. Most engineers earn between $70,000 and $110,000 a year. Many work remotely from countries like India, Brazil, and Poland. They don’t have fancy perks. No free lunches. No ping-pong tables. Just a mission.

They rely heavily on volunteers. Over 1,000 developers contribute code to MediaWiki every year. Some are students. Others are retired engineers. One contributor, a former NASA systems engineer in his 70s, still submits bug fixes every week. The team doesn’t pay them. They don’t need to. The community owns the code.

They also use open-source tools everywhere. PostgreSQL for data storage. Prometheus for monitoring. Grafana for dashboards. They don’t license proprietary software unless absolutely necessary. Even their CI/CD pipeline is built on Jenkins and GitLab - both free and open.

Security and Censorship Resistance

Wikipedia is blocked in countries like China, Russia, and Iran. The tech team doesn’t fight those blocks head-on. Instead, they build systems that are hard to shut down. They use end-to-end encryption for edits. They’ve designed their servers to be resilient against DDoS attacks - the kind that take down political sites during protests.

They also run Tor hidden services so users in censored regions can access Wikipedia anonymously. Over 100,000 users connect through Tor each month. The team doesn’t log IPs. They don’t track users. That’s not just privacy - it’s survival. If they collected data, governments could force them to hand it over. Instead, they’ve built systems that don’t have anything to give.

When a new vulnerability is found - like a flaw in PHP or OpenSSL - the team patches it within hours. They don’t wait for vendor updates. They’ve learned to read the source code themselves. One engineer, who used to work at a major bank, said the pace here is faster than any corporate security team he’s seen.

What’s Next? AI, Mobile, and the Future of Knowledge

They’re not chasing AI hype. But they’re not ignoring it either. The team is testing AI tools to help detect vandalism, suggest edits, and translate articles. But they’re careful. AI can’t be the editor. It can only be a helper. If an AI suggests a fact that’s wrong, it could mislead millions. So they’re building guardrails - human review layers, confidence scores, and edit trails that show exactly where AI suggestions came from.

Mobile usage now makes up over 70% of traffic. That’s why they’ve spent the last three years rebuilding the mobile interface from scratch. The new version loads in under two seconds, even on 2G networks. It’s designed for users in rural India, Nigeria, and Peru - places where data is expensive and connections are spotty.

They’re also experimenting with offline access. A project called Wikipedia Zero (now retired) gave free access in some countries. Now, they’re working with NGOs to distribute Wikipedia on USB drives and local servers in schools without internet. One pilot in rural Kenya lets students download entire science modules and study without a connection.

Why This Matters

Wikipedia isn’t just a website. It’s the most used reference source on Earth. More than Encyclopedia Britannica, more than Google’s Knowledge Panel, more than any textbook. And it’s all powered by a team that doesn’t care about stock prices or ad revenue. They care about whether a student in Lagos can find the history of the transatlantic slave trade. Whether a grandmother in Poland can learn how to use insulin. Whether a refugee in Syria can read about the laws of physics in her own language.

Their infrastructure isn’t glamorous. No one tweets about it. No one gets a TED talk for it. But without it, the free knowledge movement collapses. And that’s why this team - small, underfunded, and utterly dedicated - is one of the most important tech teams in the world.

Who runs the Wikimedia Foundation’s tech team?

The tech team is employed by the Wikimedia Foundation, a nonprofit based in San Francisco. It includes around 40 full-time engineers, sysadmins, and product designers. Many work remotely from over 20 countries. They’re supported by over 1,000 volunteer developers who contribute code, fix bugs, and review changes through public platforms like Phabricator and Gerrit.

Is Wikipedia built on cloud services like AWS or Google Cloud?

No. Wikipedia runs on its own physical servers in data centers across the U.S., Europe, and Asia. The foundation avoids public cloud providers to save costs - using cloud services at Wikipedia’s scale would cost over $100 million annually. Instead, they rely on donated hardware, discounted bandwidth from partners, and carefully optimized infrastructure.

What programming language is Wikipedia written in?

Wikipedia’s core software, MediaWiki, is primarily written in PHP. It also uses JavaScript for front-end interactions, Python for automation scripts, and SQL (MariaDB) for databases. The team avoids switching languages unless absolutely necessary - stability matters more than modern trends.

How does Wikipedia handle traffic spikes?

Wikipedia uses a combination of caching (Varnish and Redis), content delivery networks, and distributed databases to handle traffic spikes. During events like elections or major news stories, traffic can jump by 300%. The team pre-loads popular pages into cache and scales server capacity manually - they don’t rely on auto-scaling because it can fail unpredictably at their scale.

Can I contribute to Wikipedia’s codebase?

Yes. All of Wikipedia’s code is open source and hosted on GitHub and Gerrit. You don’t need to be a professional developer. Beginners can start by fixing typos in documentation, translating interface strings, or reporting bugs. The community welcomes contributions from anyone - students, retirees, or hobbyists. The team reviews every pull request publicly and provides detailed feedback.