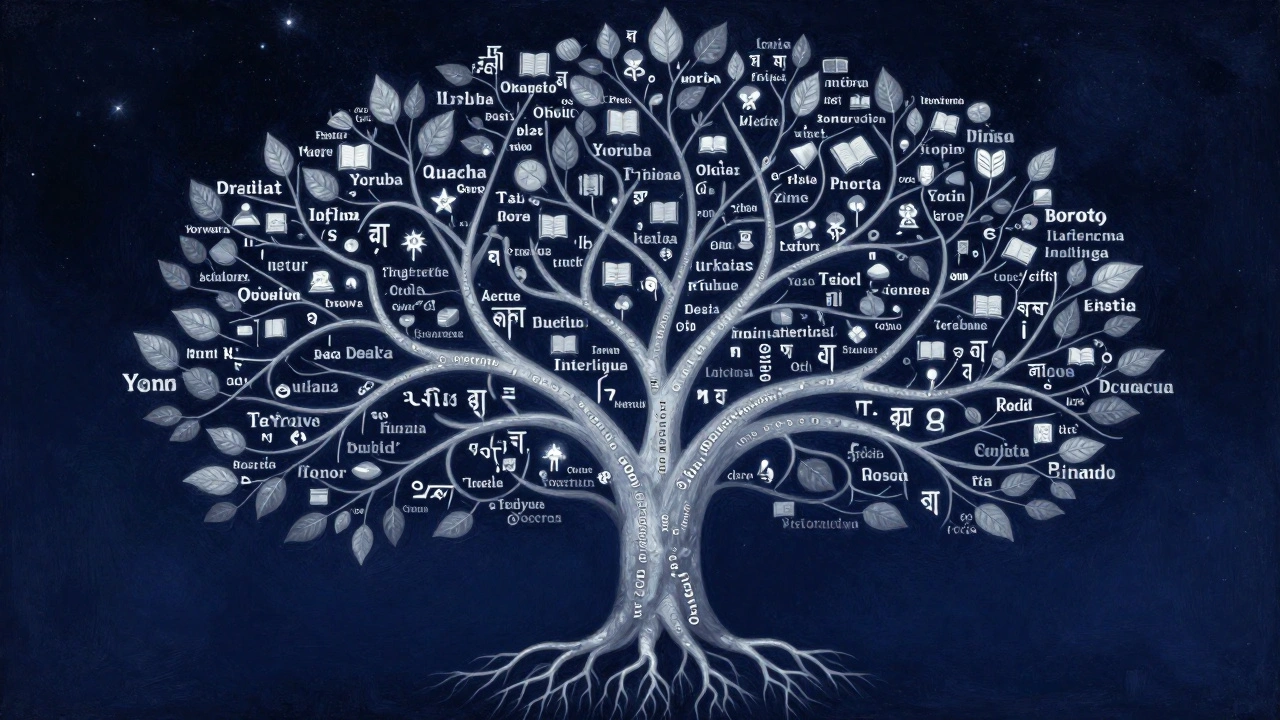

Wikipedia isn’t just one website. It’s over 300 versions of the same idea, each speaking a different language, shaped by different cultures, and built by people who’ve never met. You can read about the history of the Aztecs in Nahuatl, learn how to fix a motorcycle in Swahili, or find the rules of a local board game in Icelandic. This isn’t a translation project. It’s a collection of independent encyclopedias, all connected by the same software, the same values, and the same quiet revolution in how knowledge is made.

How Wikipedia Became a Multilingual Giant

The first Wikipedia launched in January 2001, in English. By the end of that year, there were two more: German and French. Today, there are 327 active language editions. Not all are big. Some have fewer than 1,000 articles. Others, like English, have over 60 million. But size doesn’t tell the whole story. What matters is who’s writing them-and why.

Wikipedia doesn’t force translations. It doesn’t send editors to rewrite content from English into other languages. Instead, it lets each language community build its own content from scratch. A person in Vietnam writes about local rice farming traditions because they grew up with them. A volunteer in Finland adds details about Arctic wildlife because they’ve seen it firsthand. The result? Knowledge that’s not just translated, but rooted.

There’s no central authority deciding what gets written. No editor in San Francisco approves articles in Bengali or Quechua. Each language community runs itself. They set their own rules, their own standards, their own tone. Some are strict about citations. Others rely on oral history. That’s not a flaw. It’s the point.

The Languages You’ve Never Heard of on Wikipedia

Most people think of Wikipedia in terms of major languages: Spanish, Chinese, Arabic. But the real magic happens in the smaller ones.

Take Interlingua, a constructed language designed to be easy for speakers of Romance languages to understand. It has over 100,000 articles-more than Welsh or Thai. Why? Because it’s used by a global network of language enthusiasts who see it as a neutral bridge between cultures.

Or Guarani, spoken by millions in Paraguay. Its Wikipedia has more than 120,000 articles, many written by teachers and students in rural schools. It’s one of the few places where traditional medicinal plants are documented with local names and uses, not just scientific ones.

Even Sesotho, spoken by about 6 million people in southern Africa, has a thriving Wikipedia with articles on local music, political movements, and oral storytelling traditions that don’t appear anywhere else online.

These aren’t footnotes. They’re full-fledged knowledge ecosystems. And they exist because someone, somewhere, decided their language mattered enough to write in.

What Happens When a Language Has No Wikipedia

There are over 7,000 languages spoken today. Wikipedia has editions in about 327 of them. That means over 95% of the world’s languages still have no Wikipedia.

For many, the barrier isn’t lack of interest-it’s lack of tools. Many languages don’t have standardized keyboards, spell checkers, or digital fonts. A speaker of Yupik in Alaska might know hundreds of words for snow, but typing them on a phone is hard. A writer in Tarahumara in Mexico might want to document traditional healing rituals, but there’s no way to easily format diacritics or upload audio recordings.

That’s why projects like the Language Garden and Wikipedia Zero (now defunct but influential) tried to help. They built simple mobile editors, trained local volunteers, and worked with universities to digitize old texts. Some languages got their first Wikipedia articles through handwritten notes scanned into phones.

It’s not perfect. But it’s progress. And it’s happening quietly, in villages and refugee camps, in classrooms and home offices.

How Articles Are Created Without a Central Editor

Imagine writing an article about the 1998 floods in Bangladesh. In English Wikipedia, you’d need citations from academic journals, news reports, and government data. In Bengali Wikipedia, you might cite a local newspaper, a community leader’s interview, or a video posted on Facebook by a neighbor who lived through it.

Each language community decides what counts as reliable. English Wikipedia values peer-reviewed sources. But in Swahili Wikipedia, oral testimony from elders is accepted as valid if it’s consistent across multiple sources. In Arabic Wikipedia, classical texts from medieval scholars are treated as primary sources.

There’s no global rulebook. Each edition has its own verifiability standard. And that’s why you’ll find the same topic covered very differently across languages. The English article on climate change might focus on carbon emissions. The Maori Wikipedia article might focus on how rising sea levels are eroding ancestral burial grounds. Neither is wrong. They’re just different perspectives.

The People Behind the Words

Wikipedia’s global network isn’t made of tech giants or paid editors. It’s made of volunteers. Teachers. Students. Retirees. Farmers. Refugees.

In Ukrainian Wikipedia, volunteers rushed to document war crimes as they happened, often using encrypted apps and mobile data. In Armenian Wikipedia, editors worked through internet blackouts to preserve historical records. In Tagalog Wikipedia, high school students created articles about local heroes-teachers, midwives, fishermen-because no one else was writing about them.

There’s no salary. No title. No recognition beyond the edit history. Yet, these people show up. Day after day. Because they believe their language deserves to be part of the world’s memory.

One editor in Yoruba Wikipedia once said: "If my grandmother’s stories aren’t written down, they’ll disappear. And then who will remember who we were?"

Why This Matters Beyond Wikipedia

Wikipedia isn’t just a website. It’s a mirror of the world’s linguistic diversity. And in a time when languages are disappearing faster than ever-about one every two weeks-it’s one of the last places where small languages aren’t just preserved, but actively used to build knowledge.

When a child in Nepal looks up "how to grow potatoes" in Nepali and finds a detailed guide written by a neighbor, that’s not just information. It’s dignity. It’s proof that their language isn’t outdated. It’s powerful enough to teach, to explain, to save lives.

When a scientist in Brazil writes about medicinal plants in Guarani, they’re not just sharing data. They’re challenging the idea that science only speaks English or Portuguese. They’re saying: knowledge doesn’t need a global language to be valid.

Wikipedia doesn’t fix inequality. But it gives people a tool to fight it-with words, not weapons.

What’s Next for the Multilingual Wikipedia

Wikipedia’s future isn’t about adding more languages. It’s about making existing ones better. That means more tools for editing on mobile phones. More support for audio and video. More collaboration between language communities.

There’s a growing push to let users switch between languages on the same page-so you can read about the Eiffel Tower in French, then click to see how it’s described in Hausa or Korean. Some test versions already do this.

And there’s a quiet movement to connect Wikipedia with local libraries, schools, and radio stations. In parts of Africa and Southeast Asia, community radio hosts now read Wikipedia articles on air, then invite listeners to call in and add corrections. That’s not just education. It’s co-creation.

Wikipedia will never be perfect. It’s messy. It’s slow. It’s full of gaps. But it’s alive. And it’s growing-not because of money or power, but because millions of people believe that knowledge should belong to everyone, in their own words.

How many languages does Wikipedia support?

As of 2026, Wikipedia has 327 active language editions. Each one is a separate website with its own editors, rules, and content. Some have millions of articles, while others have only a few hundred. The number changes slightly each year as new communities form and others become inactive.

Is Wikipedia translated from English?

No. Wikipedia does not automatically translate articles from English. Each language edition is written independently. Editors in each community create content based on local knowledge, sources, and interests. While some articles may be inspired by English ones, they’re rewritten from scratch to fit cultural context and available sources.

Which Wikipedia has the most articles?

The English Wikipedia has the most articles, with over 66 million as of 2026. It’s followed by Cebuano (over 58 million), German (over 2.8 million), French (over 2.7 million), and Swedish (over 2.6 million). The Cebuano edition’s high count comes from bot-generated articles about towns and biological species, not human-written content.

Can anyone create a new Wikipedia in their language?

Yes. Anyone can propose a new Wikipedia edition if they have a group of at least 10 active editors who can produce a minimum of 10 high-quality articles. The proposal goes to the Wikimedia Foundation, which reviews it for viability, community support, and technical readiness. If approved, the new edition gets its own domain, like yo.wikipedia.org for Yoruba.

Why do some small-language Wikipedias have more articles than larger ones?

Some small-language Wikipedias, like Cebuano, have huge article counts because bots automatically generate articles-often about geographic locations or biological species-using data from other sources. These aren’t written by people. In contrast, a language like Icelandic may have fewer articles but far more detailed, human-written content. Quantity doesn’t always mean quality.