Wikipedia isn’t just a collection of articles-it’s a living archive shaped by real people with real expertise. But here’s the question most people never ask: Do you need to be an academic to edit Wikipedia well? The answer isn’t simple. Thousands of editors have PhDs. Many more have no degrees at all. And yet, the quality of articles on medicine, physics, or ancient history often hinges on who’s writing them-and why they care enough to keep editing.

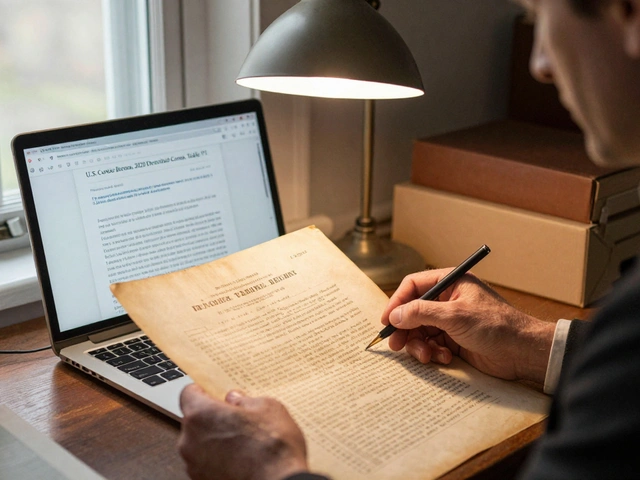

Academic Experts Are Overrepresented in High-Quality Articles

If you look at the most cited, most stable Wikipedia articles-those with dozens of references and few edit wars-you’ll find a pattern. Articles on quantum mechanics, clinical guidelines for diabetes, or the history of the Roman Empire are often maintained by people with formal credentials. A 2021 study from the University of Oxford tracked 12,000 Wikipedia articles across science disciplines and found that 38% of top contributors had published peer-reviewed research in the same field. That’s not a coincidence. These editors don’t just copy-paste from textbooks. They check primary sources, correct outdated data, and flag misleading summaries.

Take the article on CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. It’s been edited over 4,200 times since 2012. The most active editors? A molecular biologist at Stanford, a bioethics professor in Berlin, and a postdoc at the University of Cambridge. They don’t edit for fame. They edit because they’ve seen misinformation spread in medical blogs and news outlets. One of them told researchers, “I spend two hours on this article every month because I know a student might use it to write a paper.”

But Most Wikipedia Editors Aren’t Academics

Still, only about 1 in 20 Wikipedia editors globally have a PhD. The vast majority are volunteers with full-time jobs outside academia-teachers, librarians, engineers, retirees, students. Many have no formal training in the subjects they edit. Yet they contribute just as much, if not more, to general knowledge topics: pop culture, local history, sports, hobbies.

Consider the article on 1990s Nickelodeon TV shows. It’s detailed, well-sourced, and updated weekly. Who edits it? A former TV archivist from Ohio, a film student in Manila, and a fan in Sydney who spent years collecting episode guides from old magazines. None have academic titles. But they know the material inside out. Their expertise isn’t institutional-it’s obsessive.

This split matters. Wikipedia doesn’t require credentials to edit. It requires reliable sources. That means an amateur with access to primary documents can out-edit a professor who relies on secondhand summaries. The system rewards accuracy, not titles.

The Demographics of Expertise: Who’s Editing What?

Wikipedia’s editor base is overwhelmingly male, educated, and from Western countries. About 85% of active editors identify as male, and nearly 70% live in North America or Europe. That skews the content. Articles on European history are more detailed than those on African oral traditions. Articles on climate science are robust; articles on indigenous medicine often lack depth or are outright missing.

But here’s where things get interesting: when experts from underrepresented regions do join, they transform articles. In 2023, a team of Nigerian historians began expanding the article on Yoruba religious practices. Within six months, it went from 300 words with two citations to over 5,000 words with 87 references-including interviews, archived oral histories, and local academic journals previously ignored by Western editors. The article now has more citations than the English Wikipedia article on Norse mythology.

Expertise isn’t tied to geography. It’s tied to access. When people from non-Western academic systems get the tools and confidence to edit, they don’t just add facts-they correct bias.

How Academic Training Helps (and Hurts) Wikipedia Editing

Academics bring discipline. They know how to find peer-reviewed journals. They cite properly. They avoid original research. These are huge advantages. But they also bring habits that clash with Wikipedia’s culture.

Some professors treat Wikipedia like a thesis. They write long, dense paragraphs full of jargon. They insist on citing obscure papers no one else can access. Others get frustrated when their edits are reverted-not because they’re wrong, but because they violate Wikipedia’s neutral tone policy. One philosophy professor spent months trying to add a 2,000-word analysis of Kant’s ethics to the main article. It was deleted. Not because it was inaccurate-but because Wikipedia isn’t a platform for original interpretation.

The best academic contributors don’t try to publish their research on Wikipedia. They summarize it. They simplify. They link to their own papers in the references, not in the body. They treat the article like a portal, not a publication.

What Happens When Experts Don’t Show Up?

When experts stay away, misinformation fills the gap. The article on vaccines and autism was plagued by pseudoscience for over a decade. It took a team of epidemiologists, public health nurses, and science communicators-many of them volunteers-to systematically clean it up. They didn’t just delete false claims. They replaced them with clear summaries of major studies, including the 2019 Danish cohort study with 650,000 children that found no link.

That same pattern repeats in articles on mental health, nutrition, and climate change. Without experts, Wikipedia becomes a battleground for ideology. With them, it becomes a trusted source.

Can You Be an Expert Without a Degree?

Yes. And you already are-if you’ve spent years reading, verifying, and correcting facts. A retired librarian in Chicago who spent 40 years cataloging rare medical texts knows more about 19th-century treatments than most medical students. A high school teacher in rural India who translates scientific papers into Hindi for her students has deep expertise in science communication.

Wikipedia doesn’t ask for your CV. It asks: “Can you prove this?” If you can cite a government report, a peer-reviewed study, or a primary source from a trusted archive-you qualify. Your title doesn’t matter. Your ability to find, verify, and explain matters.

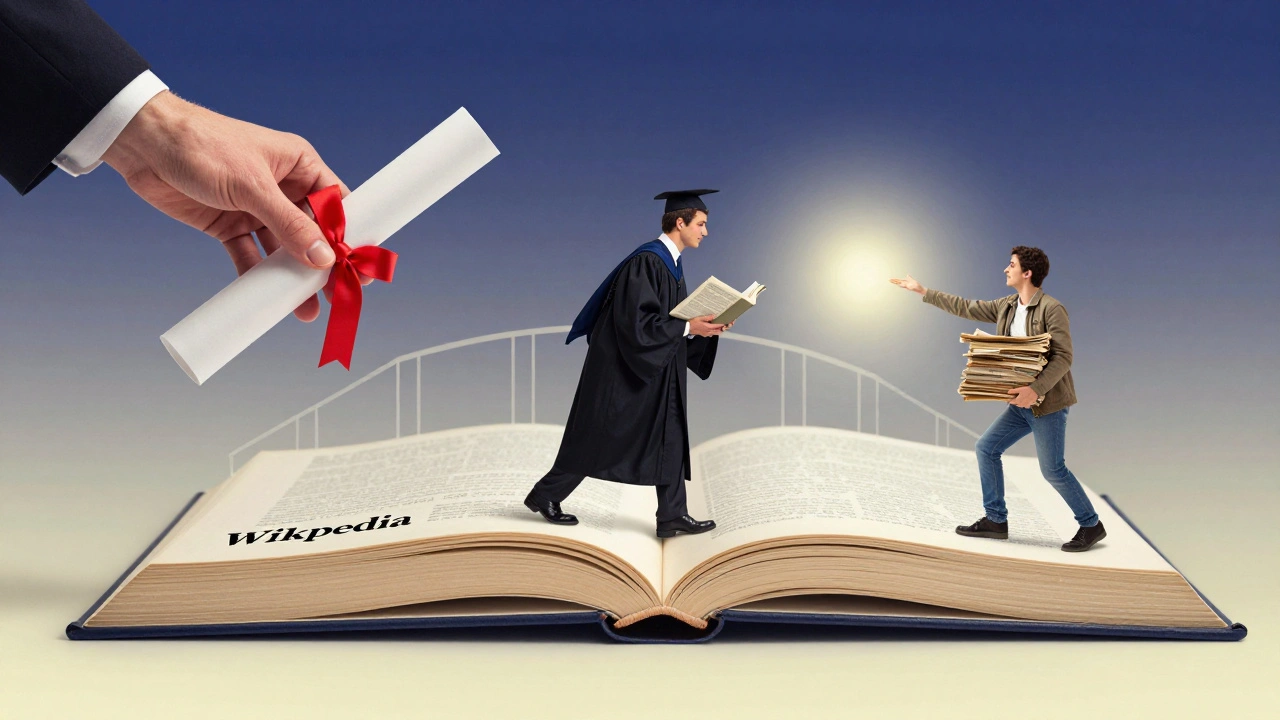

Why This Matters for the Future of Knowledge

Wikipedia is the fifth most visited website in the world. Millions of students, nurses, journalists, and curious people rely on it every day. If only academics edit science articles, we risk creating a knowledge system that’s accurate but narrow. If only fans edit pop culture, we risk losing depth and context.

The real power of Wikipedia isn’t in its technology. It’s in its diversity. The best articles come from the overlap between academic rigor and lived expertise. A historian with a PhD and a community archivist with decades of oral records can together build something neither could alone.

That’s why encouraging more academics to edit Wikipedia isn’t about boosting their credentials. It’s about strengthening the public’s access to truth. And it’s why anyone with time, curiosity, and a commitment to accuracy-even without a degree-can be a vital part of the world’s largest encyclopedia.

Do you need a PhD to edit Wikipedia?

No, you don’t need a PhD. Wikipedia’s rules require reliable sources, not academic titles. Many top editors have no formal degrees. What matters is your ability to find credible references, write clearly, and follow Wikipedia’s neutral point of view policy.

Are academic editors more reliable than non-academic ones?

Not always. Academic editors often bring strong sourcing skills and attention to detail, especially in technical fields. But non-academic editors-like librarians, journalists, or passionate hobbyists-often know niche topics better. The most accurate articles usually combine both: expert sourcing from academics and deep contextual knowledge from non-academics.

Why are most Wikipedia editors male and from Western countries?

Historically, Wikipedia’s early adopters were tech-savvy, English-speaking users from North America and Europe. Cultural barriers, language gaps, and lack of outreach to non-Western academic communities have kept participation uneven. Efforts are growing to recruit editors from Africa, Asia, and Latin America, but progress is slow. The result is content that reflects Western perspectives more than global ones.

Can Wikipedia be trusted if anyone can edit it?

Yes, for most general topics. Wikipedia has automated tools and volunteer editors who monitor changes in real time. High-traffic articles, especially on science and medicine, are protected and reviewed constantly. Studies show Wikipedia’s accuracy rivals that of Encyclopædia Britannica on factual topics. The key is checking the references at the bottom of each article.

How can academics start contributing to Wikipedia?

Start small. Pick one article in your field that’s incomplete or outdated. Add a well-cited paragraph from your research, using a reliable source like a journal or government report. Don’t write like you’re publishing a paper-keep it clear and neutral. Use Wikipedia’s “Teahouse” community for help. Many universities now offer workshops to train faculty and students in Wikipedia editing.