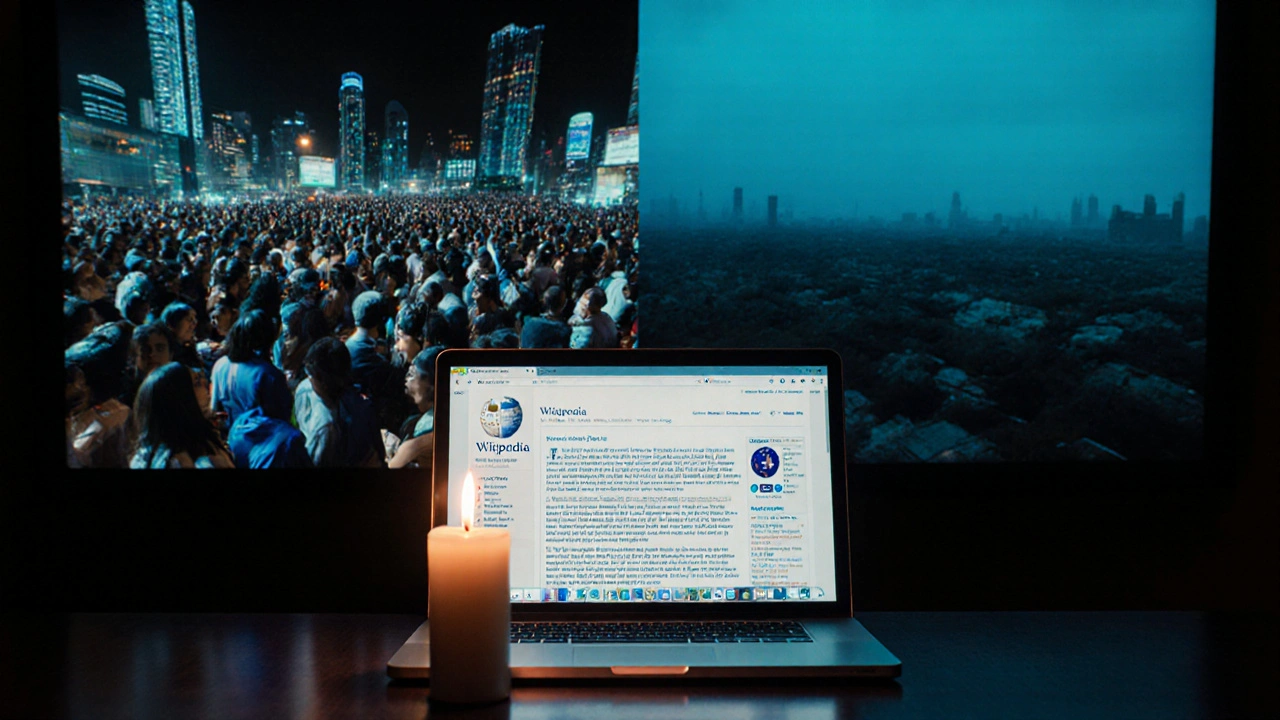

When a major event happens - like a global election, a natural disaster, or the death of a famous person - Wikipedia doesn’t just update. It explodes. Thousands of editors rush in, making hundreds of edits per minute. But who are these people? And why do they show up when they do?

Editor spikes aren’t random - they follow clear patterns

During the 2020 U.S. presidential election, Wikipedia saw over 1.2 million edits in a single day. That’s more than double its usual daily volume. The same thing happened during the 2023 Israel-Hamas conflict, the 2024 European Parliament elections, and the death of Pope Francis in early 2025. These aren’t accidents. They’re predictable surges.

Research from the Wikimedia Foundation shows that 70% of these spikes come from a small group of experienced editors - people who’ve made over 1,000 edits in the past year. These aren’t casual users. They’re volunteers who track breaking news, monitor reliable sources, and know exactly how to update articles under pressure.

But here’s the twist: most of them aren’t journalists. They’re teachers, engineers, students, retirees. One editor in Toronto, who’s made over 40,000 edits, works as a high school history teacher. Another in Berlin is a retired librarian. They don’t get paid. They don’t have titles. But they’re the backbone of Wikipedia’s real-time accuracy.

Who shows up - and who doesn’t

Wikipedia’s editor base isn’t evenly distributed. About 80% of active editors come from just 10 countries. The U.S., Germany, Japan, Russia, and the U.K. dominate. During global events, editors from countries directly affected often flood the pages with local context.

During the 2023 Turkey-Syria earthquake, Turkish editors made over 15,000 edits to the earthquake article in 48 hours. They added details about rescue efforts, casualty numbers from local sources, and maps of affected neighborhoods - information that international editors often missed.

But editors from Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America are underrepresented. When major events happen there - like the 2024 floods in Nigeria or the political crisis in Haiti - edits still spike, but slower. And the edits often come from outside the region. That creates gaps. Local knowledge gets lost. Misinformation lingers longer.

Wikipedia’s own data shows that articles about events in low-income countries are 37% less likely to be updated within 24 hours than those in high-income countries. That’s not because people there don’t care. It’s because they have less access to stable internet, fewer tools, and less familiarity with Wikipedia’s complex editing rules.

What triggers an editor to act

It’s not just the event. It’s how the event is reported.

Editors don’t rush in because something happened. They rush in when major news outlets - like BBC, Reuters, AP, or Al Jazeera - start reporting it. Wikipedia’s policy requires verifiable sources. No tweet. No Facebook post. No blog. Only trusted media.

Once a reputable outlet publishes a headline, editors start checking. They look for:

- Official statements from governments or international bodies

- Multiple independent sources confirming the same fact

- Consistent data across reports

Then they edit. Sometimes it’s a single sentence. Sometimes it’s a full rewrite. During the 2024 Canadian wildfires, one editor updated the article 23 times in one day as new fire maps and evacuation numbers came out.

But here’s the catch: editors don’t always agree. Disputes spike during major events. One editor might add a death toll from a government press release. Another might remove it because it’s unverified. These edit wars can last hours - or days. And they’re why Wikipedia’s articles during crises often look messy before they become accurate.

The quiet heroes: bots and automated tools

Behind every human edit, there’s usually a bot working.

Wikipedia runs over 5,000 automated tools. Some flag vandalism. Others pull in data from official databases. One bot, called ClueBot NG, removes spam edits in under 10 seconds. Another, WikiProject X, automatically adds citations from news archives when a major event is detected.

During the 2024 U.S. presidential debate, a bot scanned 200 news sites and added 89 new citations to the debate article within 30 minutes. It didn’t write the summary. It just made sure every claim had a source. That’s the real magic: humans shape the story. Bots keep it honest.

But bots can’t handle nuance. They can’t tell if a quote is taken out of context. They can’t judge tone. That’s still human work. And that’s why the most critical edits during big events are always done by people.

Why some events fade fast - and others stick

Not all major events leave a lasting mark on Wikipedia.

The death of a pop star might spike edits for a day, then fade. But a war, a pandemic, or a constitutional crisis? Those stick. Why?

It’s about depth. Events that change systems - governments, laws, economies - get expanded into long, detailed articles. The 2024 U.S. Supreme Court decision on digital privacy didn’t just get a quick update. It triggered 14 new sub-articles, 37 revised sections, and over 200 citations. Editors kept working on it for weeks.

Events that are emotional but short-lived - like a celebrity’s death or a viral accident - get cleaned up fast. The article gets stabilized, then left alone. No one edits it unless someone spots a mistake.

This is why Wikipedia’s most complete articles aren’t about the biggest headlines. They’re about the ones that keep changing - the ones that matter over time.

What this tells us about online communities

Wikipedia’s editor behavior during major events is a mirror of the internet itself.

It shows how knowledge spreads - fast, uneven, and often biased toward the well-connected. It shows how trust is built - not by authority, but by verification. It shows how global collaboration works - not because everyone agrees, but because they all follow the same rules.

Wikipedia doesn’t have editors because it’s popular. It’s popular because it has editors. Real people, in real time, choosing to fix the world’s information - one edit at a time.

And when the next big event hits - whether it’s a climate disaster, a political coup, or a scientific breakthrough - you’ll see the same pattern: a rush of volunteers, a flurry of edits, a quiet battle for accuracy. And somewhere, in a home office in London, a dorm room in Manila, or a library in Lagos, someone will be making sure the truth doesn’t get lost.

Why do Wikipedia editors rush to update articles during big events?

Wikipedia editors update articles during major events because they follow strict policies requiring information to be based on reliable, published sources. When major news outlets report on an event, editors verify those reports and update articles to reflect accurate, up-to-date information. This isn’t about speed - it’s about trust. Editors know that millions of people rely on Wikipedia for real-time facts, so they act quickly to prevent misinformation.

Are most Wikipedia editors professionals or volunteers?

All Wikipedia editors are volunteers. None are paid by Wikipedia or the Wikimedia Foundation. Most are regular people - teachers, students, engineers, retirees - who care about accurate information. While some have journalism or academic backgrounds, the majority have no formal training in writing or editing. What they share is a commitment to neutrality, verifiability, and public access to knowledge.

Why are editors from some countries more active than others?

Editor activity is tied to internet access, language, and familiarity with Wikipedia’s editing system. Countries with high internet penetration and strong English or German language use - like the U.S., Germany, and Japan - have more active editors. In contrast, editors from regions with lower digital access or where Wikipedia isn’t widely used (like parts of Africa or South Asia) are underrepresented. This creates a gap in coverage, especially for local events in those areas.

Do bots replace human editors during big events?

No. Bots handle repetitive tasks - like adding citations, removing spam, or flagging vandalism - but they can’t make judgment calls. Humans decide what’s accurate, what’s relevant, and how to frame complex events. During big events, bots support editors by handling the noise, but the critical decisions - like whether to include a controversial quote or update a death toll - are always made by people.

How does Wikipedia prevent false information during fast-moving events?

Wikipedia relies on three main checks: sourcing, consensus, and rollback. Every claim must cite a reliable source. Editors debate changes on article talk pages before finalizing. If false info slips in, other editors revert it quickly. Automated tools also flag suspicious edits. During the 2024 Indian election, over 200 false claims were reverted within hours because they lacked credible sources.

Can anyone edit Wikipedia during a major event?

Yes, anyone can edit - but not everything sticks. New users often make well-intentioned changes that get removed because they lack sources or violate neutrality rules. Experienced editors monitor new edits closely during big events. If you’re new, start by reading the article’s talk page and checking the sources before editing. Your contribution matters - but only if it’s accurate and verifiable.