Wikipedia isn’t just a website-it’s a global network of people writing and editing content together. But here’s the problem: most of those people aren’t like you or me. The average Wikipedia editor is a man in his 30s or 40s, living in North America or Europe. That’s not because others don’t care-it’s because they’ve never been invited to join. Regional outreach through Edit-A-Thons and structured training is changing that. And it’s working.

Why Edit-A-Thons Work Better Than Ads

Trying to recruit new editors with online ads or social media posts? It rarely works. People don’t sign up for Wikipedia because they saw a banner. They join because someone showed them how, in a space where they felt welcome.

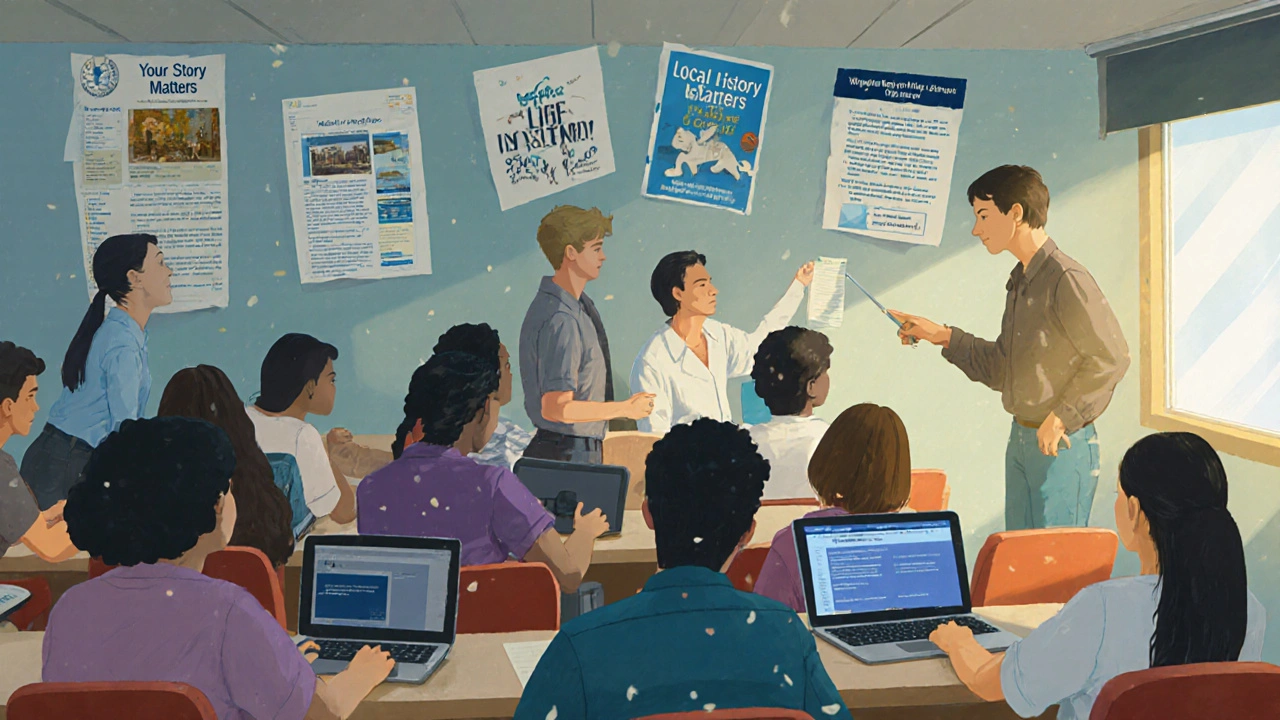

Edit-A-Thons-organized, in-person or virtual events where people gather to write or improve Wikipedia articles-are the most effective tool we have. They’re not just about editing. They’re about community. In Madison, Wisconsin, a monthly Edit-A-Thon at the public library brought in teachers, librarians, and retirees. None of them had edited Wikipedia before. By the end of the first session, three of them had created their first articles: one on local Black history, another on a forgotten women’s suffrage leader, and a third on the city’s first public library branch.

These events work because they remove the fear. New editors worry about messing up, getting blocked, or sounding stupid. At an Edit-A-Thon, someone sits next to them, walks them through the edit window, explains citation rules in plain language, and celebrates their first save. No jargon. No pressure. Just support.

Training Isn’t Optional-It’s the Foundation

Wikipedia’s help pages are full of technical terms: “semi-protection,” “talk page,” “revert.” For someone unfamiliar with wiki culture, it’s like being handed a manual written in a foreign language. That’s why training matters more than anything else.

Organizations like Wiki Education and the Wikimedia Foundation now run structured, 90-minute workshops designed for beginners. These aren’t lectures. They’re hands-on labs. Participants open a browser, pick a stub article (a short, incomplete entry), and edit it with guidance. They learn how to add a reference from a local newspaper, how to fix a broken link, how to use the visual editor instead of raw wikitext.

In rural Tennessee, a partnership between a community college and a local Wikimedia chapter trained 120 students over six weeks. Half were first-generation college students. None had edited Wikipedia before. By the end, 87 of them had made at least one edit. Ten became regular contributors. One student, who’d grown up in a town with no public library, created a detailed page on its history using interviews with elders. That article is now cited in two county history books.

Training that’s tied to real-life contexts-like local history, cultural heritage, or academic assignments-sticks. People don’t edit Wikipedia because they think it’s noble. They edit because they care about the subject.

Who’s Missing? The Data Doesn’t Lie

Wikipedia’s editor demographics are still skewed. According to the 2024 Wikimedia Community Survey, 84% of active editors identify as male. Only 16% are female. Less than 10% are from Africa, Latin America, or South Asia. In the U.S., editors from rural areas make up less than 5% of the total, even though nearly 20% of the population lives in rural communities.

These gaps aren’t accidents. They’re the result of systemic barriers: lack of access to technology, language differences, cultural norms around authority, and the perception that Wikipedia is for “experts” or “tech people.”

Regional outreach flips that. When a community center in Albuquerque hosts an Edit-A-Thon in Spanish, with materials translated and facilitators who speak both English and Spanish, participation from Latino elders and young adults jumps. When a women’s collective in rural Kerala, India, trains 30 women to write about local agriculture practices, they don’t just add content-they become the first editors from their village on Wikipedia.

It’s not about fixing the demographics. It’s about expanding them.

What Makes a Successful Regional Program

Not every Edit-A-Thon succeeds. Some fizzle out after one event. Others become lasting hubs. What’s the difference?

Successful programs share five traits:

- Local leadership-The event is led by someone from the community, not an outsider. A librarian, a teacher, a cultural organizer. Not a Wikipedia admin from Berlin.

- Clear purpose-The event has a theme: “Women in STEM from our county,” “Indigenous languages of this region,” “Local food traditions.” It’s not just “edit Wikipedia.”

- Low barrier to entry-No prior experience needed. No sign-up forms. No email required. Many use mobile-friendly tools and offer printed guides.

- Follow-up support-Participants get a contact person, a WhatsApp group, or monthly check-ins. They’re not left alone after the first session.

- Recognition-New editors are named. Their edits are highlighted. They’re thanked publicly. People want to feel seen.

In Minnesota, a program targeting Hmong-American elders started with a single event at a community center. Two years later, it has 47 active editors. They’ve added over 300 articles on Hmong history, food, and medicine. One article on traditional Hmong herbal remedies was cited by a university ethnobotany course.

What Doesn’t Work

Don’t assume everyone has a laptop. Don’t assume everyone speaks English. Don’t assume they know what a “wiki” is. Don’t hand them a 50-page PDF and say, “Good luck.”

One university tried to recruit students from a low-income campus by sending out an email with a link to Wikipedia’s help page. Only 3 students clicked it. Then they hosted a 30-minute session in the student union with laptops, snacks, and a facilitator who said, “Just pick a topic you care about and try editing.” Over 120 people showed up.

Tools matter, but human connection matters more.

How to Start Your Own Edit-A-Thon

You don’t need a big budget or a fancy website. You just need a room, a few people, and the willingness to show up.

- Find a local partner: a library, school, museum, or community center. They’ll handle space and promotion.

- Choose a simple theme: “Local landmarks,” “Famous people from our town,” “Traditions we’re losing.”

- Use the Wikipedia mobile app or the visual editor-no coding needed.

- Bring printed instructions with pictures: how to click “Edit,” how to add a source, how to save.

- Have at least one experienced editor on hand to answer questions.

- End with a group photo and a thank-you. Send a follow-up email with a link to the next event.

There’s no secret. Just show up. Be patient. Let people learn at their own pace.

The Ripple Effect

When someone edits Wikipedia for the first time, they don’t just add a sentence. They change how they see knowledge. They realize they don’t need to be an academic or a journalist to make something public. They can be a grandmother, a high school student, a farm worker.

That’s the quiet revolution happening in small towns, refugee centers, and tribal communities. Wikipedia is becoming less of a top-down encyclopedia and more of a living archive shaped by the people who live the stories.

And it’s not about numbers. It’s about who gets to tell them.

Do I need to be a tech expert to help run an Edit-A-Thon?

No. You don’t need to know how to code or understand wiki markup. Most new editors use the visual editor, which works like a word processor. All you need is patience, a willingness to sit beside someone, and the ability to say, “Let me show you.” Many libraries and community groups offer free training for volunteers-just search for “Wikimedia ambassador training.”

Can I host an Edit-A-Thon online?

Yes. Virtual Edit-A-Thons work well, especially for rural or remote communities. Use Zoom or Google Meet with screen sharing. Have a facilitator walk through an edit in real time. Share a simple link to a starter article and encourage participants to type in the chat as they go. Keep it small-10 to 15 people max-for better interaction.

What if someone edits something wrong?

Mistakes are part of the process. Wikipedia is built on collaboration. If someone adds incorrect information, another editor will fix it. The goal isn’t perfection on the first try-it’s participation. Encourage new editors to not fear edits. Show them how to use the “history” tab to see changes, and how to ask for help on an article’s talk page. That’s how learning happens.

How do I find topics that need editing in my region?

Start with Wikipedia’s “Articles for Creation” list or the “WikiProject” pages for your country or state. Look for stubs marked as “needs citation” or “needs expansion.” You can also search for your town or neighborhood name on Wikipedia-if the article is short or missing photos, that’s a great place to start. Local historical societies often have lists of missing topics too.

Is there funding available for these events?

Yes. The Wikimedia Foundation offers small grants (up to $1,000) for community-led outreach events. Many state libraries and cultural nonprofits also have funds for digital literacy programs. You don’t need a large budget-snacks, printed handouts, and a projector are often enough. The real investment is time and care.

What Comes Next?

If you’ve read this far, you already know the problem: Wikipedia doesn’t reflect the world. But you also know the solution: people, not technology, make the difference.

Start small. Invite one person. Show them how to add a sentence. Celebrate their edit. Then invite another. Before long, you won’t be running an event-you’ll be building a movement.