Ever wonder why a Wikipedia article in Japanese feels completely different from the same article in English? It’s not just about word-for-word swapping. Translation isn’t about swapping one language for another-it’s about rebuilding meaning for a new culture, context, and mindset. On Wikipedia, where millions of articles are translated daily, this process reveals deep, often invisible challenges that go far beyond grammar.

Words Don’t Have One Meaning

Take the word "privacy." In English, it’s a legal and personal right. In some languages, there isn’t even a direct equivalent. In Mandarin, the closest term is "隐私" (yǐnsī), but its cultural weight leans more toward family modesty than individual rights. When translating Wikipedia’s article on privacy, editors in China don’t just translate the text-they rewrite entire sections to reflect local norms, laws, and public understanding. What’s a fact in English might be a controversy in another language. And that’s not an error. It’s adaptation.

This happens everywhere. In Arabic, the word for "freedom" carries religious and political layers that English doesn’t. In Swahili, "democracy" isn’t just a system-it’s tied to communal decision-making traditions. Wikipedia translators don’t just find synonyms. They ask: Does this concept even exist here? If not, how do we explain it without distorting it?

Structure Follows Culture

English Wikipedia articles follow a strict formula: introduction, history, details, controversies, references. But not every culture thinks that way. In many Indigenous languages, knowledge is passed through stories, not bullet points. When translating into Quechua or Mapudungun, editors avoid rigid sections. They weave facts into narrative flow, using oral traditions as a guide. A reader in Bolivia doesn’t want a textbook. They want a story that feels like home.

Even in European languages, structure changes. German Wikipedia articles often start with dense technical definitions. French versions favor philosophical context. Russian entries may include more historical background. There’s no universal "correct" way to organize information. What works for a German engineer might confuse a Brazilian student. Translation teams have to choose: do we follow the source, or do we follow the audience?

What Gets Left Out?

Not every fact makes the cut. In 2023, researchers found that 42% of English Wikipedia articles about climate change had no equivalent in languages spoken by countries most affected by rising sea levels. Why? Because translators are volunteers. They’re not paid. They’re often working alone, with limited tools. If you’re translating from English to Yoruba and you don’t have access to reliable local sources, you can’t verify claims. So you skip sections. Or worse-you translate them anyway, and they become misinformation.

Some topics simply vanish. Indigenous knowledge, local folklore, regional history-these often don’t exist in English sources. So they’re not translated. They’re erased by default. The Wikipedia model assumes English is the hub. But for many communities, English is the barrier.

Tools Don’t Fix Culture

Machine translation tools like Google Translate or DeepL are everywhere. But they’re terrible at cultural nuance. They’ll translate "you’re welcome" as "you are welcome"-grammatically correct, but culturally wrong in Spanish-speaking countries where "de nada" carries warmth, not formality. In Japanese, "arigatou" isn’t just "thank you." It’s a social ritual. Machine translation strips that away.

Wikipedia’s own translation tools help, but they’re built for speed, not depth. The Content Translation tool auto-fills text from one language to another. But it doesn’t ask: Is this concept relevant here? Does this example make sense? Editors still have to manually fix every line. And they often spend hours just to rework one paragraph.

Who Gets to Translate?

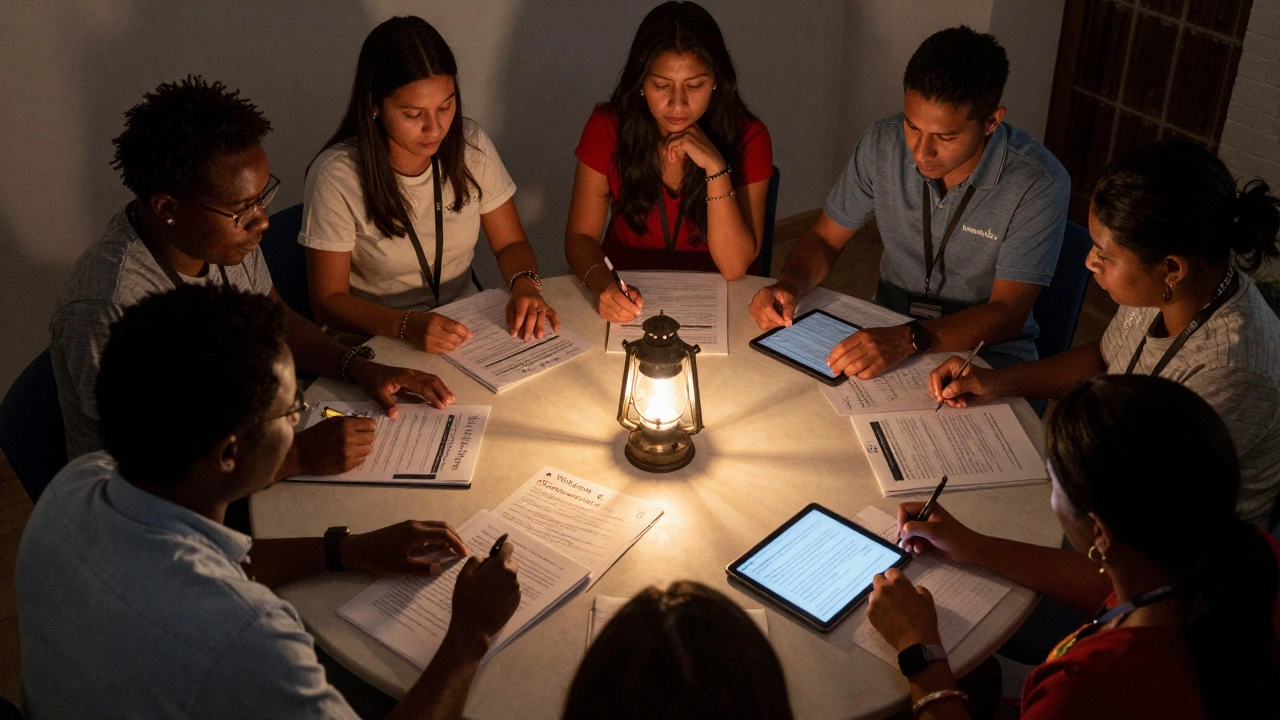

Most Wikipedia translations are done by volunteers from high-income countries. A study from 2024 showed that 80% of translations into low-resource languages came from speakers of major European languages. That means the perspective is filtered. A Vietnamese article on "family" might be translated by someone in France who’s never lived in Hanoi. The result? A version that sounds right to outsiders but feels alien to locals.

There’s a growing movement to fix this. Groups like Wikimedia Indonesia and Wikimedia Africa are training local editors to translate content into their own languages-not from English, but from other regional sources. A Thai editor might translate a Thai article from a Burmese version, not an English one. This creates a web of knowledge that reflects real connections, not colonial hierarchies.

Accuracy Isn’t the Goal-Relevance Is

Wikipedia’s mission isn’t to be perfect. It’s to be useful. A perfectly translated article that doesn’t connect with its readers is a failure. That’s why editors in Kenya don’t just translate "vaccination" from English. They add local myths about vaccines, common misconceptions, and trusted community health workers. They turn a medical fact into a conversation.

Same with gender. In languages without gendered pronouns, like Finnish or Turkish, Wikipedia editors add context about gender identity that’s missing in English versions. They don’t just translate-they expand. And that’s the real challenge: not to copy, but to enrich.

What Happens When Translation Fails?

When translation skips cultural context, misinformation spreads. In 2022, a Hindi Wikipedia article on mental health used a direct translation of "depression" as "sadness." It led to thousands of readers believing depression was just a bad mood. Editors had to rewrite the entire article, adding local terms like "manasik dard" (mental pain) and citing Indian psychiatrists.

Another example: In Arabic, the word for "homosexuality" is often tied to criminalization. Translating English articles that treat LGBTQ+ rights as universal created backlash. So some Arabic editors created separate articles that explain rights within Islamic legal frameworks, not Western ones. They didn’t reject the information-they recontextualized it.

These aren’t mistakes. They’re survival tactics. When the source material doesn’t match reality, translators have to rebuild it.

The Future Isn’t Perfect-It’s Local

Wikipedia’s translation system is broken, but it’s also evolving. More tools are being built for low-resource languages. AI models are being trained on local dialects. Volunteer networks are growing in Nigeria, Vietnam, and Peru. The goal isn’t to make every article identical across languages. It’s to make each version true to its people.

That means accepting that translation isn’t about uniformity. It’s about resonance. A fact in English might be a story in Swahili. A statistic in German might be a proverb in Quechua. The real success of Wikipedia isn’t in how many languages it speaks. It’s in how deeply it listens.

Why can’t machine translation fully replace human editors on Wikipedia?

Machine translation handles vocabulary and grammar, but it can’t understand cultural context. For example, it won’t know that "privacy" in Japan means avoiding public exposure, while in the U.S. it’s about legal rights. Human editors adjust tone, add local examples, and remove culturally irrelevant details. Without them, translations feel robotic-or worse, misleading.

Do all Wikipedia languages have the same amount of content?

No. English Wikipedia has over 6 million articles, but many languages have fewer than 10,000. Some, like Guarani or Tuvan, have under 5,000. This isn’t because those cultures have less to say-it’s because translation relies on volunteers, and resources are uneven. A language spoken by 5 million people might have less content than one spoken by 1 million if the latter has a strong volunteer community.

Can a Wikipedia article be translated from another language besides English?

Yes. While English is often the source, many translations happen between non-English languages. For example, a Spanish article might be translated into Quechua using a Spanish version as the base-not English. This is called "lateral translation," and it’s becoming more common as local communities build their own knowledge networks outside Western-centric sources.

Why do some Wikipedia articles have different facts across languages?

Because each language version is independently edited. An article in Russian might include Soviet-era history that’s omitted in English. A Chinese version might emphasize Confucian values absent in Western versions. These aren’t contradictions-they’re reflections of different perspectives. Wikipedia allows multiple truths to coexist, as long as each is well-sourced within its own cultural context.

How do translators handle slang, idioms, or humor?

They usually avoid them. Slang and humor rarely translate well. Instead, editors replace them with culturally appropriate equivalents. For example, an English joke about "Monday blues" might become "the first day back after weekend rest" in Arabic. The goal isn’t to preserve the joke-it’s to preserve the feeling. When that’s not possible, they leave it out.

What Can Readers Do?

If you use Wikipedia in a language that isn’t your first, ask: Is this version complete? Does it feel like it was made for me? If not, you can help. Join a local translation team. Add sources from your community. Edit articles to reflect local knowledge. You don’t need to be a linguist. You just need to care about your language being heard.

Translation isn’t a technical task. It’s a political act. Every time someone translates a Wikipedia article, they’re deciding: Who gets to be represented? What counts as knowledge? And who decides what’s true? The answer shouldn’t be English. It should be every language that’s willing to speak up.