Wikipedia isn’t just a place to look up facts-it’s one of the most powerful tools for teaching students how to think, not what to think. Every day, millions of people open Wikipedia to learn about climate change, political movements, or medical debates. But here’s the thing: those articles don’t come with a warning label. They don’t say, "This section is disputed," or "Half the experts disagree." That’s on you to figure out. And that’s exactly why it’s perfect for teaching critical thinking.

Why Wikipedia Works for Critical Thinking

Most textbooks present information as settled. But real life isn’t like that. In the real world, people argue over data, interpret evidence differently, and change their minds when new facts appear. Wikipedia mirrors that messiness. Take the article on vaccines. It doesn’t just say vaccines are safe. It shows you the history of public fear, the studies that confirmed safety, the retracted papers that caused panic, and how media coverage shifted over time. You see the debate unfold-not as a lecture, but as a living document edited by thousands.

When students read Wikipedia articles on controversial topics, they’re not just absorbing information. They’re learning to ask: Who wrote this? What sources are cited? Is there a pattern of edits from one side? Are there unresolved disputes flagged at the top? These aren’t just skills for school-they’re survival skills in a world flooded with misinformation.

How to Turn a Wikipedia Page Into a Classroom Exercise

Start simple. Pick one controversial topic-say, gun control in the United States. Give students the Wikipedia page and ask them to do three things:

- Find the "Controversy" or "Debate" section. What claims are being made on each side?

- Click every citation. How many are from peer-reviewed journals? How many are from blogs, opinion pieces, or news outlets with clear bias?

- Check the "Talk" page. What arguments did editors have? Who kept reverting edits? Why?

Then compare that to a textbook summary. The textbook says: "Gun control laws reduce violence." Wikipedia says: "Studies show mixed results depending on methodology, region, and enforcement." One gives you an answer. The other gives you a map to find your own.

Another exercise: Track how an article changes over time. Go to the history tab of the Abortion article. Look at edits from 2010 versus 2025. Notice how language shifts-from "unborn child" to "fetus," from "right to life" to "bodily autonomy." These aren’t random changes. They reflect evolving public understanding, legal rulings, and editorial consensus. Students learn that knowledge isn’t static-it’s negotiated.

The Hidden Curriculum: Understanding Bias and Reliability

Wikipedia doesn’t pretend to be neutral. It admits it’s a work in progress. That’s its strength. The site flags articles with issues like "neutrality concerns," "original research," or "citation needed." Students who learn to spot these tags start noticing the same patterns elsewhere-in news headlines, social media posts, even political speeches.

One teacher in Wisconsin had her class analyze the Wikipedia article on climate change denial. They found that while the scientific consensus was clearly stated, the article also included a section titled "Arguments by climate change deniers," with each claim followed by a rebuttal citing peer-reviewed studies. The students were shocked. "Why don’t TV news shows do this?" one asked. Because TV needs soundbites. Wikipedia needs evidence.

By learning to read Wikipedia’s structure-its citations, its dispute flags, its edit histories-students develop a mental checklist: Who says this? How do they know? What’s missing? Is this being disputed? These habits stick. They carry over to research papers, job applications, even family dinner conversations.

What Students Get That Textbooks Don’t

Textbooks are curated by committees. They smooth out edges. They avoid controversy to keep publishers happy. Wikipedia is crowdsourced, imperfect, and alive. It doesn’t hide the fact that people disagree. It documents how those disagreements play out in real time.

For example, the Wikipedia page on gender identity includes subsections like "Legal recognition," "Medical consensus," and "Criticism and controversy." Each has citations from the American Psychological Association, the World Health Organization, and independent researchers. But it also includes critiques from groups that reject the science. Students aren’t told which side is right. They’re shown how to weigh evidence, identify credible sources, and recognize when someone is cherry-picking data.

This isn’t about teaching students to doubt everything. It’s about teaching them to doubt wisely. To ask: Is this claim supported? Is this source trustworthy? Is this being challenged by experts?

Common Misconceptions and How to Fix Them

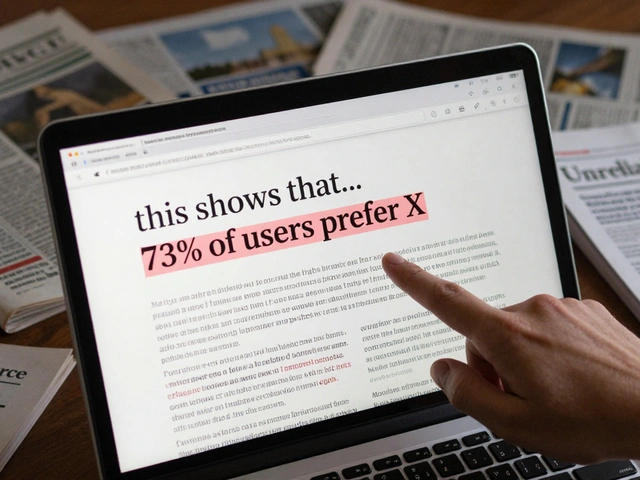

Some teachers avoid Wikipedia because they’ve heard it’s unreliable. But research tells a different story. A 2021 study from the University of Oxford compared Wikipedia articles on 100 scientific topics with peer-reviewed encyclopedias. The accuracy rate was nearly identical. The difference? Wikipedia was updated 17 times faster.

Another myth: "Students will just copy-paste from Wikipedia." That’s true-if you don’t teach them how to use it. But if you show them how to trace citations, evaluate sources, and write their own summaries based on evidence, they stop copying. They start thinking.

One high school in Madison had students write a research paper using only Wikipedia as a starting point. They had to find three sources cited in the article, read the original papers, and then write a new section adding their own analysis. Half the class ended up correcting errors in the Wikipedia article. One student even got their edit approved by the community.

Real-World Impact: Beyond the Classroom

When students learn to navigate Wikipedia’s complexity, they become better consumers of information in every part of life. They’re less likely to fall for viral misinformation. They question headlines that say "Scientists Prove..." without checking the source. They understand that a single study doesn’t change reality-it’s the weight of evidence that matters.

Imagine a student who’s been taught to read Wikipedia critically. They see a TikTok video claiming a new drug "cures depression." Instead of sharing it, they search Wikipedia for "depression treatment." They see the list of FDA-approved therapies, the meta-analyses, the side effect data. They don’t panic. They don’t believe. They investigate.

That’s not magic. That’s critical thinking. And Wikipedia is one of the few places where that skill can be practiced safely, openly, and at scale.

Getting Started: A Simple Lesson Plan

Here’s how to begin:

- Choose one controversial topic relevant to your curriculum: immigration, artificial intelligence, evolution, or cryptocurrency.

- Give students the Wikipedia page. Ask them to highlight any claims that feel too strong or too vague.

- Have them click on three citations. Read the original source. Did the article accurately represent it?

- Check the "Talk" page. Find one edit dispute. What was the argument? Who won? Why?

- Write a short reflection: "What did you learn about how knowledge is made?"

It takes one class period. The impact lasts years.

What Comes Next?

Once students get comfortable with Wikipedia, they’re ready for deeper work. They can compare how different language versions cover the same topic. They can analyze how cultural bias shapes content. They can even contribute to Wikipedia themselves-editing for clarity, adding citations, fixing inaccuracies.

Wikipedia isn’t the end of the journey. It’s the starting line. It’s where students learn that truth isn’t handed to them. It’s built-piece by piece, edit by edit, by people who care enough to check the facts.

Can Wikipedia be trusted for school assignments?

Wikipedia shouldn’t be cited as a final source, but it’s excellent for finding reliable sources. Every well-written article includes citations to peer-reviewed journals, books, and official reports. Students should use Wikipedia to locate those sources, then read and cite them directly. This teaches them how to trace information back to its origin.

Why do Wikipedia articles on controversial topics change so often?

They change because real-world events change. New studies come out. Laws are passed. Public opinion shifts. Wikipedia reflects that. The article on "climate change" today is different from 2015 because the science has advanced and more data is available. These edits are reviewed by volunteers who follow strict sourcing rules. Frequent changes don’t mean unreliability-they mean the article is alive and responsive.

Is Wikipedia biased toward certain viewpoints?

Wikipedia has a policy of neutral point of view (NPOV), but it’s not perfect. Some articles show bias because editors from one side dominate the discussion. That’s why students should check the "Talk" page and edit history. If you see the same user repeatedly removing dissenting views, that’s a red flag. The goal isn’t to eliminate bias-it’s to teach students how to detect it.

How do I know if a Wikipedia article is well-written?

Look for these signs: a clear structure, balanced coverage of viewpoints, citations for every major claim, and a "References" section with credible sources. Articles marked as "Good Article" or "Featured Article" by Wikipedia’s community meet higher standards. Also check the talk page-healthy debate and revisions indicate active, thoughtful editing.

Should students be allowed to edit Wikipedia?

Yes-when guided properly. Editing Wikipedia teaches responsibility, research skills, and collaboration. Many universities now assign Wikipedia editing as part of their curriculum. Students learn to write for a public audience, follow citation rules, and defend their edits with evidence. It’s one of the most authentic learning experiences available.