Most people know Wikipedia as the free online encyclopedia everyone uses to look up facts. But did you know Wikipedia isn’t alone? It’s part of a bigger family of free knowledge tools, all run by the same nonprofit behind it. These are called Wikipedia’s sister projects. They don’t just support Wikipedia-they expand what’s possible when knowledge is open to everyone.

What Are Wikipedia’s Sister Projects?

Wikipedia’s sister projects are free, community-driven platforms that handle different kinds of information. While Wikipedia collects summarized articles, these other tools take on things like raw texts, structured data, media files, and translations. They all share the same mission: to make knowledge freely accessible and editable by anyone.

These projects aren’t side notes. They’re the backbone of how Wikipedia stays accurate, updated, and rich with sources. Without them, Wikipedia would be missing critical pieces-like where its facts come from, how quotes are verified, or how images are licensed.

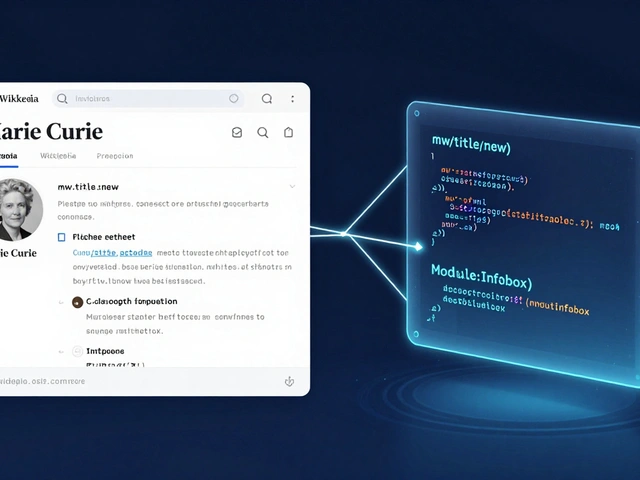

Wikidata: The Central Database Behind the Facts

Think of Wikidata as the invisible engine powering Wikipedia’s facts. It’s not a website you read like an encyclopedia. It’s a giant, structured database where facts are stored as simple statements: Albert Einstein was born in Ulm, Germany, on March 14, 1879.

Each fact in Wikidata is broken into parts: a subject (Albert Einstein), a property (date of birth), and a value (March 14, 1879). This structure lets computers understand relationships between things. That’s why you can search for “scientists born in 1879” and get a clean list-even if no Wikipedia article says that exact phrase.

Wikidata feeds data directly into Wikipedia articles. When you see a box on the right side of a Wikipedia page with birth dates, nationalities, or awards, that’s often pulled from Wikidata. If someone updates the birth year of a scientist in Wikidata, it updates automatically across hundreds of Wikipedia pages in different languages.

It’s also used by tools like Google’s Knowledge Graph and Apple’s Siri. That means your phone or search engine might be pulling facts from a project you’ve never heard of-because Wikidata makes it easy for machines to understand real-world relationships.

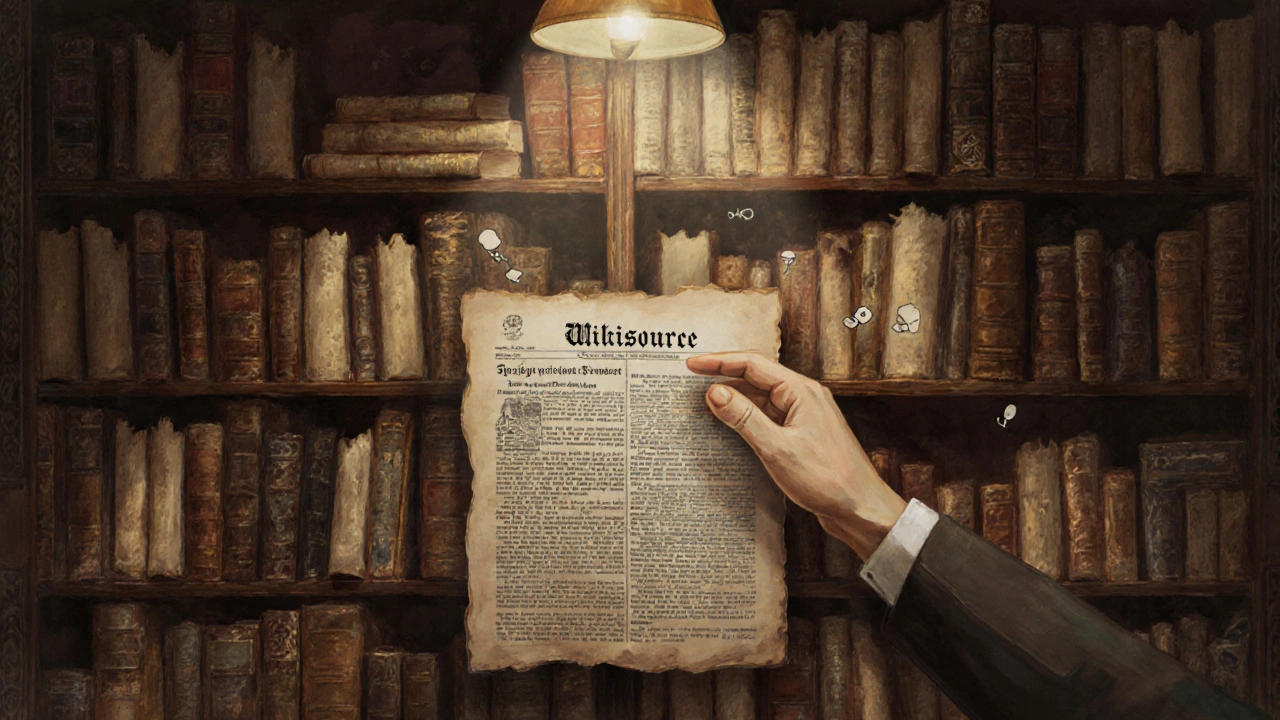

Wikisource: The Library of Original Texts

Wikipedia summarizes what others have written. Wikisource hosts the originals.

This project is a digital library of public domain and freely licensed texts. You’ll find full versions of classic books like Pride and Prejudice, historical documents like the U.S. Constitution, old newspapers, letters from inventors, and even ancient religious texts-all scanned, proofread, and formatted for easy reading.

Why does this matter? Because Wikipedia articles need reliable sources. If a Wikipedia editor cites a quote from Mark Twain, they can link directly to the exact page on Wikisource where that quote appears. That’s transparency. That’s trust.

Volunteers spend hours comparing scanned pages with typed text to catch typos. A single page of a 1920s newspaper might take hours to verify. But when done right, it preserves history exactly as it was written-not rewritten or summarized.

Wikisource isn’t just for books. It includes legal codes, treaties, speeches, and even song lyrics that are no longer under copyright. If it’s free to use and historically valuable, Wikisource likely has it.

Wikimedia Commons: The Free Media Hub

Every image, video, and sound file you see on Wikipedia? Most of them come from Wikimedia Commons.

Commons is a central repository for media files that anyone can use-freely, without paying or asking permission. It holds over 100 million files: photos of wildlife, historical maps, diagrams of DNA, audio recordings of bird calls, even 3D models of ancient artifacts.

Unlike stock photo sites, everything here is either in the public domain or licensed under Creative Commons. That means teachers can use a photo of the Mona Lisa in a classroom presentation. A student can embed a video of a lunar eclipse in a science project. A journalist can use a map of war zones without legal risk.

Uploaders must tag each file with clear licensing info and source details. A photo of a building? You need to say who took it and when. A sound clip of a frog? You must confirm it’s not copyrighted music. This system keeps Commons clean and usable for everyone.

Commons also powers tools like Wikipedia’s infoboxes and featured article galleries. It’s not just background art-it’s essential evidence.

Wikiquote: Quotes, Exactly as Said

When someone says something memorable-“I have a dream,” “Elementary, my dear Watson”-Wikiquote collects those exact words.

This project isn’t about interpretations or summaries. It’s about preserving the original phrasing of quotes from famous people, books, movies, and even internet memes. Each quote is attributed clearly: who said it, where, and when.

Why is this useful? Because Wikipedia editors often cite quotes to support claims. If an article says “Steve Jobs believed design was everything,” Wikiquote links to his actual commencement speech where he said that. No guessing. No misquoting.

Wikiquote also includes quotes from fictional characters, like Darth Vader’s “I am your father,” and even humorous or viral lines from TikTok videos-if they’ve been widely referenced in reliable sources.

It’s the only place where you can find a curated, verified collection of real quotes without the noise of random social media posts.

Wiktionary: The Open Dictionary

When you look up a word on Wikipedia, you might get a definition-but it’s usually brief. For full definitions, etymology, pronunciation, and translations, you go to Wiktionary.

It’s a multilingual dictionary that covers over 1,700 languages. You can find how “hello” is said in Swahili, the origin of the word “robot,” or the different meanings of “run” in British vs. American English.

Unlike traditional dictionaries, Wiktionary updates in real time. New slang like “rizz” or “cheugy” gets added quickly because real people use them. It also includes technical terms from coding, medicine, and law-terms that commercial dictionaries often ignore.

Each entry has sections: pronunciation guides with IPA symbols, synonyms, antonyms, usage examples, and even translations into other languages. It’s not just for students-it’s for translators, writers, and anyone who cares about language.

Wikiversity: Learning Without a Classroom

Wikipedia teaches you what things are. Wikiversity teaches you how to learn them.

This project hosts free learning materials: lesson plans, quizzes, research projects, and even full online courses. You’ll find guides on how to write a research paper, tutorials on basic statistics, or interactive modules on climate science.

It’s used by teachers who want to assign free, open-source materials. It’s used by self-learners who don’t want to pay for Coursera or edX. It’s even used by universities to host open educational resources.

Unlike YouTube tutorials, Wikiversity content is peer-reviewed and designed for structured learning. A lesson on “Introduction to Logic” might include readings, exercises, and a final quiz-all linked together.

It’s not flashy. But it’s powerful. And it’s growing.

Wikinews: Real-Time Reporting, Not Summaries

Wikipedia doesn’t cover breaking news. Wikinews does.

This project publishes original news articles written by volunteers using neutral, factual reporting. It covers events like elections, scientific discoveries, and community protests-but only if they’re well-documented and verifiable.

Unlike blogs or social media, Wikinews follows journalistic standards: attribution, multiple sources, no opinion. If a volcano erupts, Wikinews won’t say “It’s terrifying.” It will say, “The eruption on Mount St. Helens on April 12, 2025, forced the evacuation of 12,000 people, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.”

It’s not as big as Reuters or the BBC. But it’s one of the few places where you can read a news story written entirely by volunteers, with every claim backed by public sources.

Why These Projects Matter

These sister projects aren’t just cool side projects. They’re what make Wikipedia reliable.

Without Wikidata, Wikipedia’s fact boxes would be manually updated-and full of errors. Without Wikisource, quotes would be misattributed. Without Commons, articles would be empty of images. Without Wiktionary, definitions would be vague.

They’re also what make knowledge truly free. You don’t need a subscription. You don’t need to create an account. You don’t need to pay. You just need curiosity.

And if you’re ever stuck trying to find a source, verify a quote, or understand a technical term-you don’t have to search the whole internet. One of these projects already has it.

How to Use Them

Here’s how to start using them:

- When you see a Wikipedia article with a fact box, click the “View data” link to see the source in Wikidata.

- When a quote is cited, click the link to go to Wikisource or Wikiquote and read the original.

- When you need an image, search Wikimedia Commons instead of Google Images.

- When you’re unsure what a word means, check Wiktionary before using a paid dictionary.

- When you want to learn something new, try a Wikiversity course.

You don’t have to edit them to benefit from them. But if you do, you’re helping build a better world of knowledge.

Are Wikipedia’s sister projects run by the same organization?

Yes. All of them are operated by the Wikimedia Foundation, the same nonprofit that runs Wikipedia. They share the same mission: to collect and distribute free knowledge. Each project has its own community of editors, but they all follow the same open licensing rules and technical standards.

Can anyone edit these projects?

Yes. Almost all of them are open for anyone to edit, just like Wikipedia. You don’t need to sign up, though creating an account helps you track your edits and build trust in the community. Some pages may be protected if they’re frequently vandalized, but most content is open for collaboration.

Do these projects have mobile apps?

Not officially. The Wikimedia Foundation doesn’t build separate apps for each sister project. But you can access them through any web browser on your phone. There are also third-party apps like “Wikiwand” or “Kiwix” that let you browse Wikipedia and some sister projects offline.

Why aren’t these projects as popular as Wikipedia?

They’re not designed to be. Wikipedia is for quick summaries. The others serve specialized needs: data, sources, media, definitions. Most people don’t need to use them unless they’re doing deeper research. But if you ever need to fact-check, cite a source, or find a free image, you’ll be glad they exist.

Are these projects available in multiple languages?

Yes. Wikidata, Wiktionary, and Wikisource exist in over 100 languages. Wikimedia Commons is mostly in English, but media files are labeled in their original languages. Wikiversity and Wikinews have smaller language communities, but content is growing. The goal is global access-not just English.