Wikipedia runs on millions of edits every day. Most come from real people, but behind the scenes, thousands of automated tools - bots - are quietly helping keep the site running. If you’ve ever wondered who’s making those tiny fixes, cleaning up vandalism, or updating templates across hundreds of articles, you’re looking at bot infrastructure. And the best way to understand what these bots are doing? Tools like XTools and other Wikipedia editor analysis platforms.

What XTools Actually Does

XTools isn’t just another dashboard. It’s a suite of tools built by volunteers to show you what editors - human or bot - are doing on Wikipedia. Type in a username, and it pulls data: how many edits they’ve made, when they last edited, which namespaces they work in, and even which articles they’ve touched most. For bots, this is especially useful. You can see if a bot is stuck in a loop, over-editing a single page, or accidentally breaking templates.

For example, if a bot named "AutoArchiver" is making 500 edits an hour, XTools will show you that. It doesn’t tell you if it’s good or bad - but it gives you the facts. You can check if those edits are all in Talk pages (normal for archiving bots) or if they’re randomly altering article content (a red flag). The tool also breaks down edits by time of day. Some bots run during off-hours to avoid conflicts. Others? They’re active at 3 a.m. and 3 p.m. That pattern tells you something about their design.

Other Platforms You Should Know

XTools is popular, but it’s not the only game in town. Several other platforms serve different parts of the editor analysis puzzle.

- WikiStats - Run by the Wikimedia Foundation, this gives you high-level stats: total edits by user, edit count by namespace, and edit frequency over time. It’s less user-friendly than XTools but more authoritative. If you need to verify if a bot is violating edit rate limits, WikiStats is where you go.

- AWB (AutoWikiBrowser) - Not an analysis tool, but a bot-building tool. Many bots are built using AWB, and its logs can be cross-referenced with XTools to trace edit patterns. If you see a bot making edits with the same comment format every time, it’s likely AWB-driven.

- Contributions API - The raw data source behind most tools. Developers use this to build custom dashboards. If you’re technically minded, you can query it directly to see every edit made by a user since 2001. No filters. Just raw data.

- Wikipedia:Editcount - A simple page that shows a user’s total edit count. It’s outdated for detailed analysis but still useful for a quick sanity check. If someone claims they’ve made 10,000 edits, but Editcount says 2,000, something’s off.

Each tool has its role. XTools gives you context. WikiStats gives you scale. AWB tells you how bots are built. Together, they form a complete picture of Wikipedia’s automated editing ecosystem.

How Bots Are Classified and Monitored

Not all bots are created equal. Some are approved. Some are experimental. Some are rogue.

Approved bots on Wikipedia have to go through a formal process. They need a bot flag, which means they’re allowed to bypass certain edit limits. To get that flag, the bot operator must submit a detailed proposal: what the bot does, how often it edits, how it handles errors, and who’s responsible if it breaks something. Then the community votes.

Once approved, bots are tracked. Their edits are tagged with a bot flag in the edit history. That’s why tools like XTools can separate bot edits from human ones. You can filter your search to show only bot edits - useful if you’re trying to find out if a bot is overcorrecting grammar or deleting useful citations.

But not all bots are approved. Some run without permission. These are called "unflagged bots" or "shadow bots." They’re harder to detect, but tools like XTools still catch them. If a user has 15,000 edits in a month and 98% of them are minor template fixes - and they’ve never edited a talk page - it’s probably a bot. Community members often flag these for review.

Why This Matters to Wikipedia

Wikipedia isn’t just a website. It’s a living system. Bots handle the boring, repetitive, high-volume tasks that humans can’t or won’t do. They fix broken links. They update infoboxes. They revert vandalism within seconds. Without them, Wikipedia would collapse under its own scale.

But bots can also cause harm. A misconfigured bot once deleted 10,000 articles in 2014 because of a bug in its template parser. Another bot, designed to fix spacing, removed all hyphens from article titles. These aren’t hypotheticals - they happened. And they were caught because someone used XTools or WikiStats to notice the pattern.

The tools don’t stop bots. They make bots visible. That visibility is what keeps Wikipedia healthy. When you can see what’s happening, you can respond. You can warn. You can block. You can fix.

Real-World Use Cases

Here’s how people actually use these tools in daily Wikipedia work:

- A new editor joins Wikipedia and wants to know if their edits are helpful. They use XTools to compare their edit count and article quality metrics against experienced users. It shows them they’re overusing bold text - a common rookie mistake.

- A volunteer notices a spike in edits to a popular article. They check WikiStats and see that a bot named "LinkFixer" made 2,000 edits in 4 hours. They look at the edit summaries and realize the bot is replacing outdated links with broken ones. They report it.

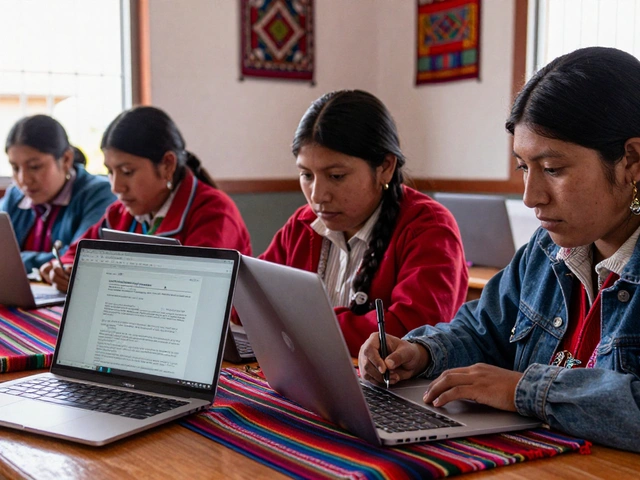

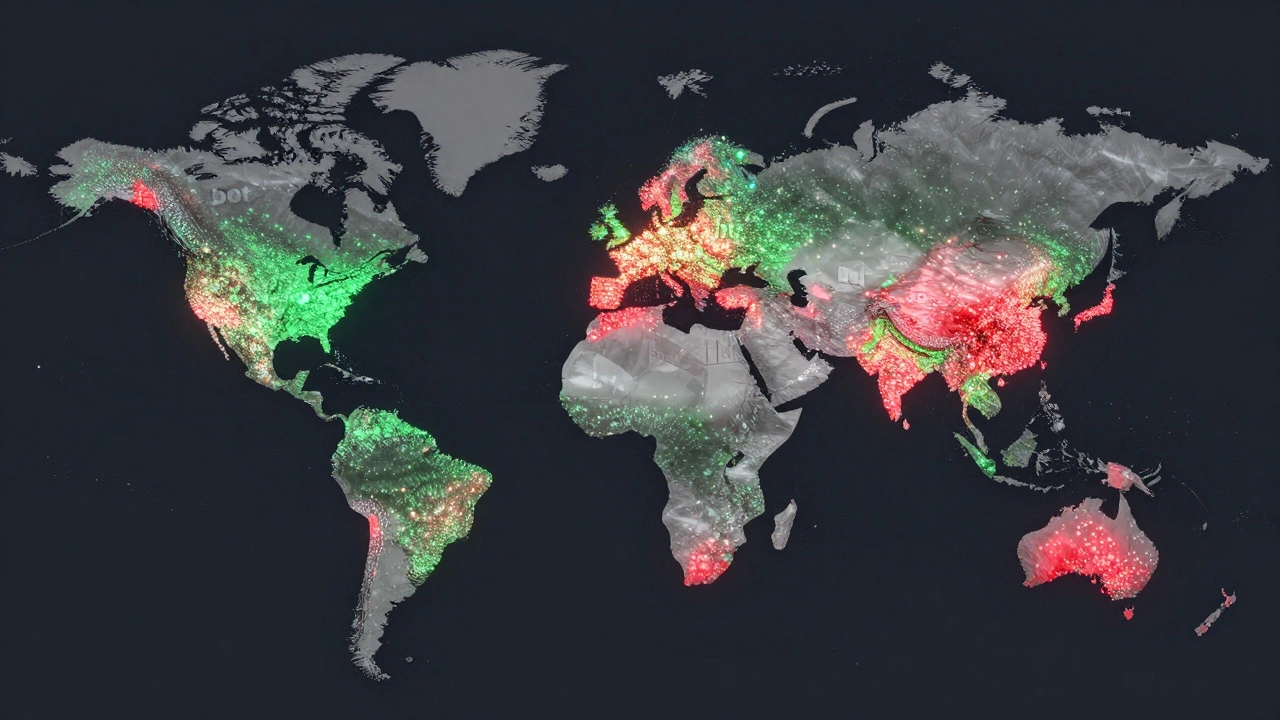

- A researcher studying collaboration patterns on Wikipedia uses the Contributions API to pull all edits made by bots in 2025. They analyze the data to see which types of bots are most active in different language editions.

- An admin reviews a bot operator’s request for a flag. They cross-check the bot’s history in XTools and find that the bot made 70% of its edits in the User namespace - a sign it’s still being tested. They ask for more data before approving.

These aren’t edge cases. They’re everyday scenarios. The tools aren’t flashy. They don’t have ads or mobile apps. But they’re essential.

Limitations and Pitfalls

These platforms aren’t perfect. They have blind spots.

First, they can’t tell you why an edit was made. They show the change, but not the intent. A bot might fix a citation, or it might be inserting fake references. You need human judgment to decide.

Second, they don’t track edits across all Wikimedia projects. XTools shows Wikipedia edits, but not Commons uploads or Wikidata changes. If a bot works across multiple projects, you need to check each one separately.

Third, some bots are designed to hide. They use multiple accounts. They rotate user agents. They edit during low-traffic hours. These are harder to detect - and sometimes impossible without manual investigation.

And finally, data delays. XTools updates every 15 minutes. WikiStats updates daily. If a bot goes rogue at 11:55 p.m., you might not see it until morning. That’s why community vigilance matters more than any tool.

What’s Next for Editor Analysis Tools

The future of these tools is moving toward automation - but not in the way you think.

Instead of building more dashboards, developers are embedding analysis into the editing interface itself. New browser extensions now warn editors in real time: "This edit matches patterns seen in 87% of bot edits." Or: "You’re editing 12 articles in 3 minutes - are you using a bot?"

Machine learning is also being tested. One experiment uses historical edit data to predict whether a new account is likely to be a bot. It’s not perfect - false positives are common - but it’s getting better.

And there’s growing interest in cross-project analysis. What if you could see a bot’s edits across Wikipedia, Wiktionary, and Wikisource in one view? That’s the next frontier. The data exists. The tools just need to connect it.

How to Get Started

If you’re curious about how bots work on Wikipedia, here’s how to start:

- Go to XTools and enter any username. Look at the edit distribution. What patterns do you see?

- Check the same user on WikiStats. Compare the numbers. Do they match?

- Look at the edit summaries. Are they repetitive? Do they say "Bot: Fixing link"? That’s a clue.

- Search for "bot" in the user’s talk page. If they have a bot flag, it’ll be listed.

- Try filtering edits by namespace. If 90% are in Template or Category space, it’s likely automated.

You don’t need to code. You don’t need to be an admin. You just need to look. And once you start looking, you’ll start seeing the invisible labor that keeps Wikipedia alive.

Can XTools detect if a bot is malfunctioning?

Yes. XTools shows edit frequency, edit patterns, and namespace usage. If a bot suddenly starts editing 10 times more than usual, or starts editing articles instead of talk pages, it’s a red flag. You can’t see the code, but you can see the behavior - and that’s often enough to spot a problem.

Are all bots on Wikipedia approved?

No. Only about 30% of bots have official approval. Many operate without a flag, especially small tools that fix punctuation or update links. These "unflagged bots" are allowed as long as they don’t break rules. But if they cause harm, they’re quickly disabled.

Can I build my own bot using these tools?

You can’t build a bot with XTools or WikiStats - they’re for analysis, not creation. But they help you understand how existing bots behave, which is critical before building your own. To create a bot, you’d need to use AWB, Pywikibot, or another bot framework. But studying edit patterns with XTools is the first step.

Do these tools work for non-English Wikipedias?

Yes. XTools and WikiStats support all language editions. You can analyze edits on the German, Japanese, or Swahili Wikipedia just as easily as the English one. The data is global. The tools are too.

Why don’t these tools show real-time edits?

Because Wikipedia’s servers can’t handle real-time updates for millions of users. XTools refreshes every 15 minutes. WikiStats updates daily. This delay prevents server overload. Real-time tracking would crash the system. The trade-off is accuracy for stability - and it works.