Every year, millions of students start a research project by typing a topic into Google-and the very first result is Wikipedia. It’s fast, free, and feels trustworthy. But here’s the problem: most students don’t know how to read it like a source. They treat it like a textbook. And that’s where things go wrong.

Why Wikipedia Gets Misused

Wikipedia isn’t a peer-reviewed journal. It’s a living document written by volunteers. That’s not a flaw-it’s a feature. But without context, students see the polished surface and assume authority. A 2023 study from Stanford’s History Education Group found that 78% of middle and high school students couldn’t tell the difference between a Wikipedia article and an academic paper when both looked equally professional.

It’s not that students are lazy. They’re trained to trust the top result. Teachers often say, "Just use Wikipedia to get started," but never follow up with how to move beyond it. The result? Students copy paragraphs, cite Wikipedia as a final source, and miss the real work of research: tracing ideas back to original sources.

What Wikipedia Actually Is

Wikipedia is a collaborative encyclopedia. Anyone can edit it. That means articles can be incomplete, biased, or even vandalized. But it also means they’re updated fast. A breaking news event might appear on Wikipedia within minutes. A scientific discovery can be summarized within days. That speed is powerful-but only if you know how to check it.

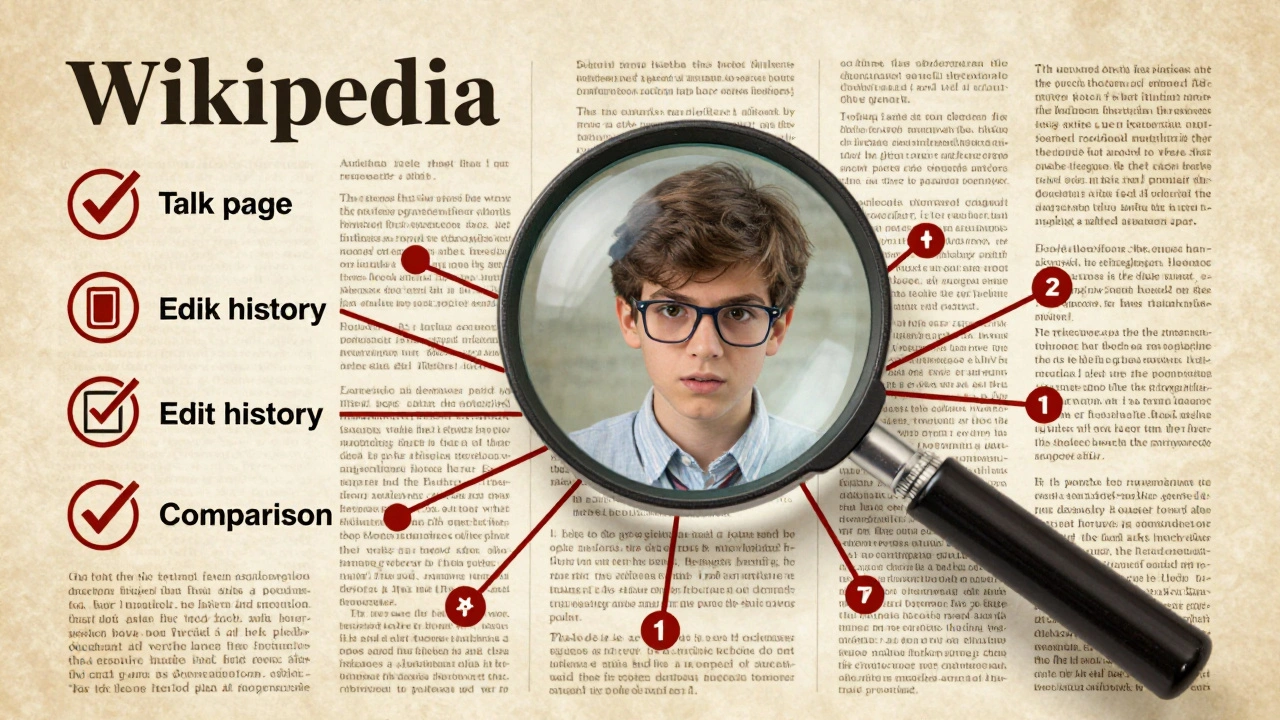

Every Wikipedia article has a "Talk" page. That’s where editors debate what belongs and what doesn’t. There’s also an "Edit history" tab that shows every change made. And every claim should have a citation-usually a link to a book, journal, or reputable news outlet. These aren’t decorations. They’re the backbone.

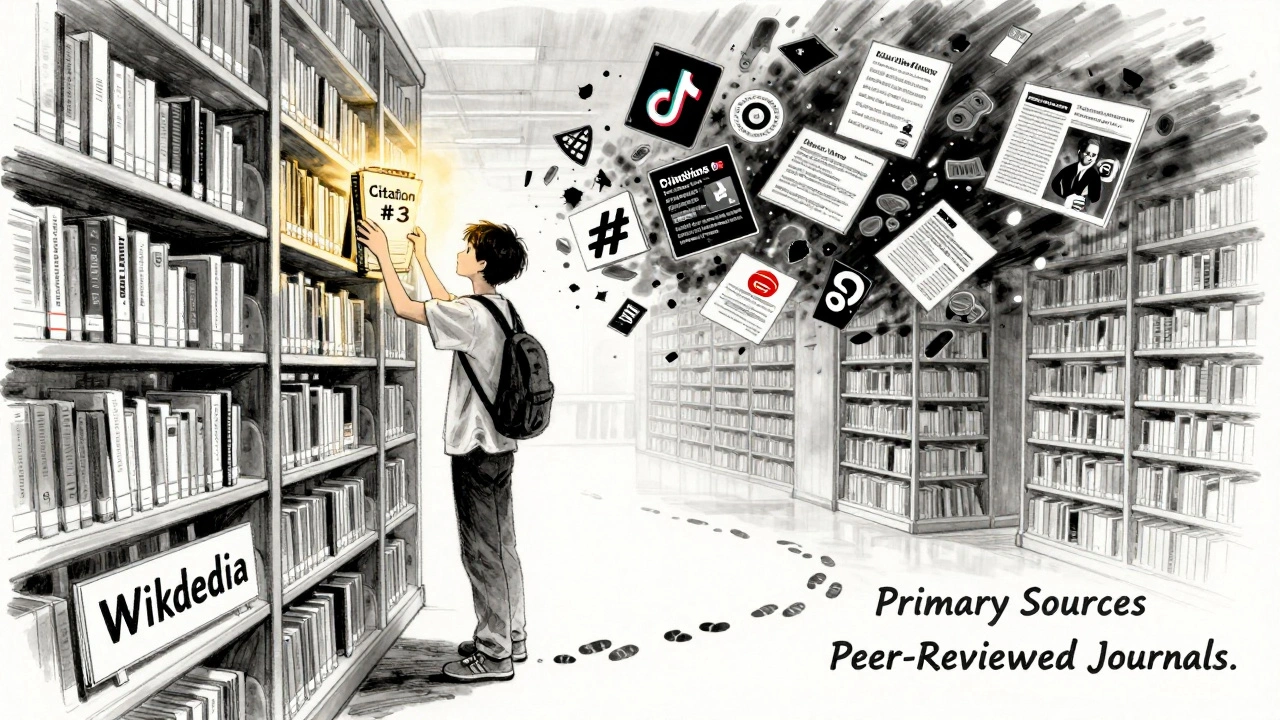

Think of Wikipedia like a public library with open shelves. You can take any book off the shelf, but you still need to know if the author is credible, if the publisher is reputable, and if other scholars agree with the argument. Wikipedia doesn’t replace that work. It just gives you a starting point.

Teaching the Five-Point Check

Instead of saying "Don’t use Wikipedia," teach students how to use it right. Here’s a simple five-point checklist that works in any classroom:

- Check the citations. Click every link. Are they from reliable sources? Look for .edu, .gov, peer-reviewed journals, or major news outlets like BBC or Reuters. If most links are blogs or personal websites, be skeptical.

- Read the Talk page. Is there a long debate about accuracy? Are editors arguing over bias? If so, the article might be contested or incomplete.

- Look at the edit history. How many editors have worked on it? Has it been edited recently? An article with hundreds of edits over years is usually more stable than one edited once by a single user last week.

- Compare with other sources. Find the same topic in a textbook, academic database, or trusted encyclopedia like Britannica. Do they say the same thing? If Wikipedia is the only source saying it, that’s a red flag.

- Don’t cite it. Use Wikipedia to find the real sources. Then go to those. Cite the original author, not the Wikipedia editor.

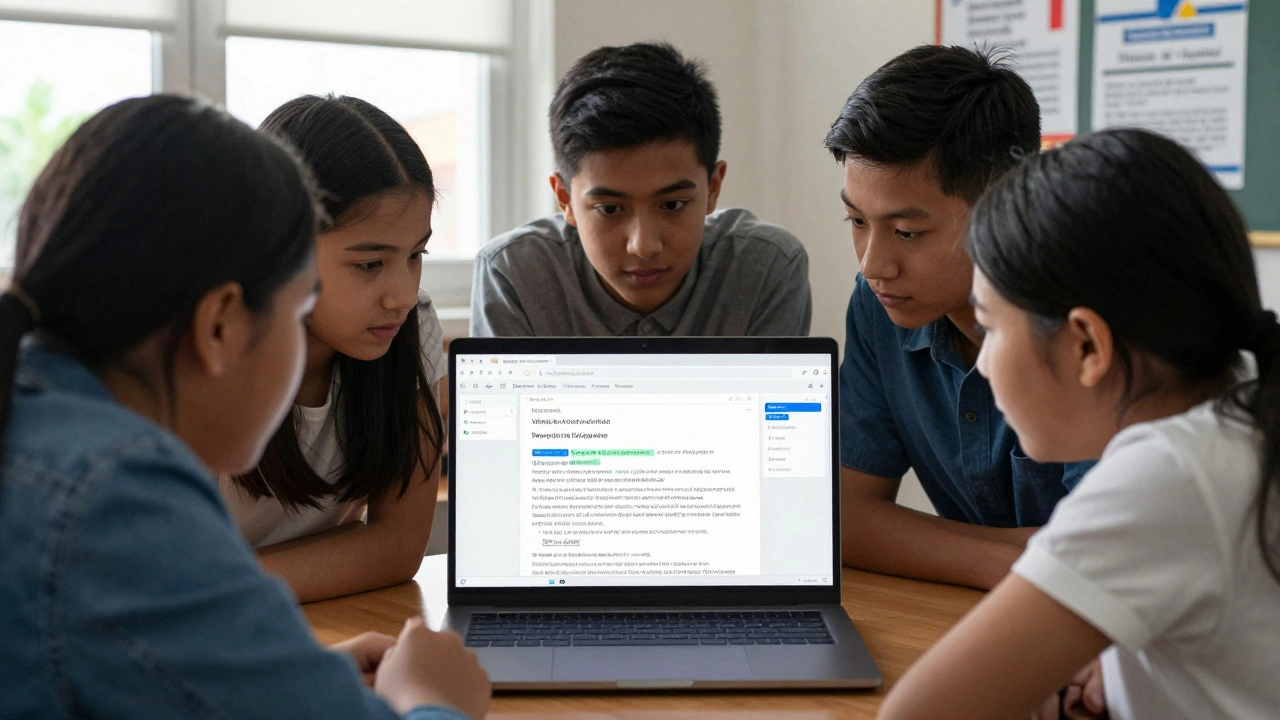

This isn’t about shutting down Wikipedia. It’s about teaching students to dig deeper. One teacher in Ohio had her students write a Wikipedia article on local history. They had to find primary sources, verify facts, and defend every edit. By the end, they could spot misinformation in seconds-even on TikTok.

The Real Skill: Source Tracing

The goal isn’t to make students Wikipedia experts. It’s to make them source tracers. That’s the core of digital literacy: following the trail from a summary back to the original evidence.

When a student reads on Wikipedia that "climate change is caused by human activity," they should ask: Who said that? Where did they publish it? What data did they use? That’s how science works. Wikipedia just gives you the headline. The real story is in the footnotes.

Students who learn source tracing don’t just do better in school. They become less likely to believe conspiracy theories, fake news, or viral misinformation. They learn to pause. To question. To look behind the curtain.

What Doesn’t Work

Many schools still use outdated methods. "Wikipedia is wrong, so don’t use it"-that’s not teaching. It’s fear-based avoidance. Students will still use it. They just won’t know how to use it well.

Another common mistake: assigning a "Wikipedia vs. Google Scholar" comparison. That’s a false binary. Wikipedia and academic journals aren’t competitors. They’re tools in different stages of research. One helps you understand the landscape. The other helps you build your argument.

What works is hands-on practice. Have students pick a controversial topic-vaccines, AI ethics, school funding-and trace one claim back to its original source. Show them how to use the citation, find the paper, read the abstract, and compare it to what Wikipedia says. That’s real learning.

Real Examples That Stick

One class in Texas looked up "The Great Depression" on Wikipedia. The article said unemployment peaked at 25%. They clicked the citation-it led to a 1936 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics report. They found the original chart. Then they compared it to a 2020 textbook that cited Wikipedia. The textbook had rounded the number to 24%. Neither was wrong. But the student who traced the number understood why the difference existed.

Another group studied the Wikipedia page on "Gender and Science." They noticed the Talk page had over 200 comments from editors arguing about word choice. One section had been edited 87 times in a month. They realized the article wasn’t neutral-it was being shaped by ongoing cultural debates. That’s not a failure. It’s a lesson in how knowledge is made.

Where Teachers Should Start

You don’t need a fancy curriculum. Start with one lesson:

- Give students a Wikipedia article on a topic they care about-sports, music, social media trends.

- Ask them to find one fact they think is true and trace it to its source.

- Then ask: What if that source was wrong? What if it was biased? What if it was outdated?

- Finally: Where would you go next to confirm it?

That’s it. No lecture. No handout. Just curiosity. And after that one lesson, students will start checking citations on their own-even when you’re not watching.

The Bigger Picture

Wikipedia literacy isn’t about one website. It’s about how we think in a world full of information. If students can’t evaluate a Wikipedia article, they won’t be able to evaluate a news headline, a political tweet, or a medical claim on Instagram.

Teaching them to read Wikipedia critically is the same as teaching them to think critically. It’s not about banning tools. It’s about giving them the skills to use any tool wisely.

And that’s the real win. Not better grades. Not perfect citations. But students who ask: "How do I know that’s true?"

Can students cite Wikipedia in research papers?

Generally, no. Most academic institutions and style guides (like APA and MLA) don’t accept Wikipedia as a formal citation because it’s not a primary or peer-reviewed source. Instead, students should use Wikipedia to find credible references listed in its citations-then cite those original sources directly.

Is Wikipedia accurate enough for school projects?

It can be, but only if students verify the information. Studies show that Wikipedia’s accuracy on scientific and historical topics is often comparable to Encyclopedia Britannica. However, accuracy varies by topic. Popular subjects like pop culture or current events are usually well-maintained. Niche or controversial topics may have gaps or bias. Always check citations and edit history.

Why do teachers say not to use Wikipedia?

Many teachers discourage Wikipedia because students have historically used it as a final source without digging deeper. It’s not that Wikipedia is unreliable-it’s that students were never taught how to use it as a starting point. The goal is to move beyond it, not avoid it.

How can I tell if a Wikipedia article is well-written?

Look for these signs: at least 10-15 credible citations, a detailed "References" section, a "Talk" page with active discussion, a long edit history with multiple contributors, and no warning banners like "Citation needed" or "Possible bias." Articles marked as "Good Article" or "Featured Article" on Wikipedia have passed formal review.

Does Wikipedia have bias?

Yes, but it’s not always obvious. Wikipedia tries to follow a neutral point of view, but its editors are human. Topics like politics, gender, and history often reflect the perspectives of the most active contributors, who tend to be from Western, English-speaking countries. Checking the Talk page and comparing with non-English versions can reveal hidden biases.