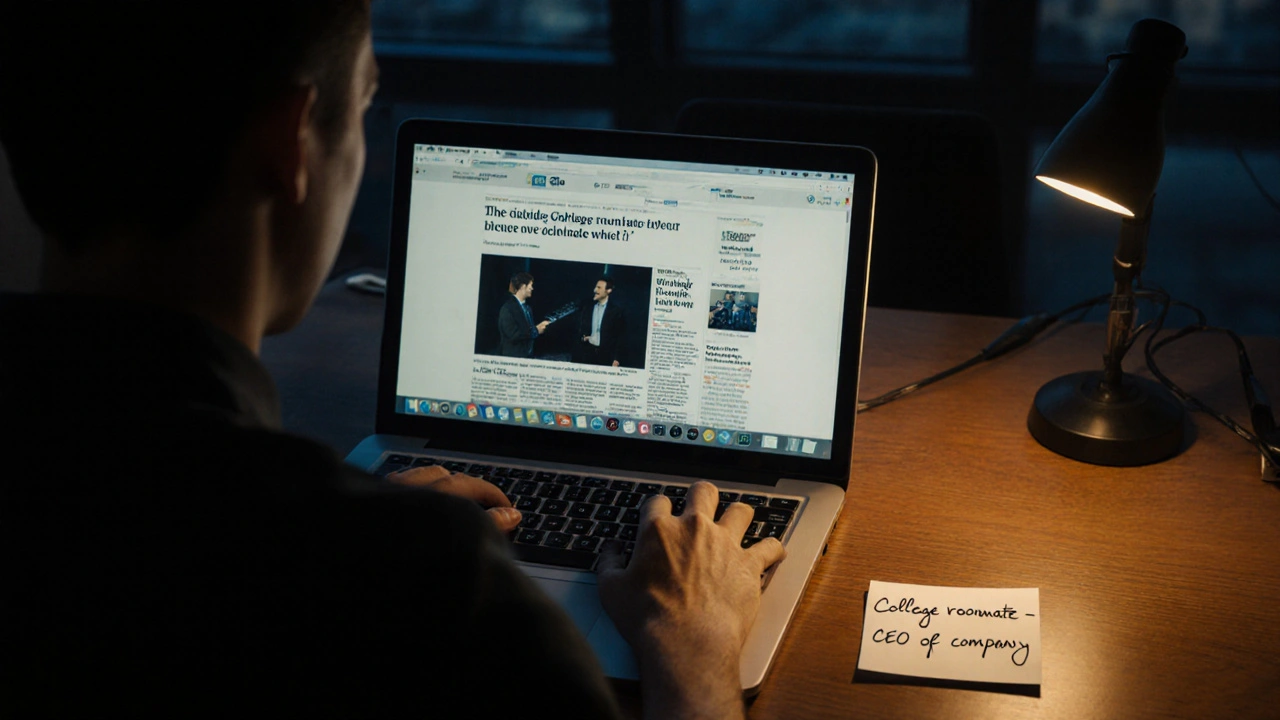

When an editor writes about a company whose CEO is their college roommate, or reviews a book by their spouse, or covers a city council vote where their sibling is running for office - what happens to the story? The truth doesn’t vanish. But trust does. And that’s where conflict of interest policies aren’t just paperwork. They’re the last line of defense for credibility.

What a Conflict of Interest Really Looks Like

A conflict of interest isn’t always a shady deal. It’s often something quiet: a lunch with a source, a shared investment, a past job at the organization you’re now reporting on. In 2023, a major U.S. news outlet retracted a feature on clean energy startups after it was revealed the lead editor owned stock in two of them. The story was well-researched. The data was accurate. But the reader didn’t care. They saw a conflict - and lost faith.That’s the problem. People don’t need perfect reporting. They need to believe the reporter isn’t playing both sides. A 2024 Pew Research study found that 68% of Americans distrust media because they think journalists have hidden agendas. Most of those people couldn’t name a single biased article. They just know someone somewhere is getting something out of it.

How Policies Evolved From ‘Don’t Be Corrupt’ to ‘Disclose Everything’

In the 1980s, most newsrooms had one rule: don’t take bribes. That was it. If you didn’t accept cash from a source, you were clean. But as media became more specialized - tech reporters covering Silicon Valley, health reporters tracking pharmaceuticals - the lines blurred. A reporter might get invited to a free conference. A food critic might be invited to a restaurant opening. A science editor might have a cousin who works at a biotech firm.By the early 2010s, organizations like the Society of Professional Journalists and the Associated Press started requiring full disclosure. Not just ‘don’t take money’ - but ‘tell us if you have any connection, no matter how small.’ The shift wasn’t about suspicion. It was about transparency. If you know your editor’s brother works for the company, you can judge the story yourself. If you don’t know - you assume the worst.

Today’s best policies don’t just ask editors to declare conflicts. They ask them to recuse themselves. If you’ve ever worked at a company, even briefly, you can’t cover it. If you’ve received free travel from a nonprofit you’re writing about, you’re off the story. No exceptions. That’s the standard now at The New York Times, ProPublica, and Reuters.

Where Policies Fail - And Why

Policies look good on paper. But they break down when people don’t report their own ties. Why? Because it’s uncomfortable. It’s awkward. Sometimes, editors think, ‘It’s just a coffee.’ Or, ‘They’re not influencing me.’In 2022, a national magazine published a long-form piece on mental health apps. The author had received funding from one of the apps for a prior research project - a fact they never disclosed. The piece was praised for its depth. Readers later found out. The magazine issued an apology. The author left. But the damage stuck. That one story became a symbol of what’s wrong with media.

Another problem: vague definitions. Some policies say ‘avoid conflicts.’ But what counts as a conflict? Is a Facebook friend a conflict? What if you went to college with the CEO? What if your spouse works in the same industry? Without clear thresholds, editors guess - and guess wrong.

That’s why the most effective policies now list specific examples:

- Ownership of stock in a company you cover - automatic recusal

- Family member employed by the subject of your story - must disclose and step aside

- Previous employment at the organization within the last five years - cannot report on it

- Free travel or lodging from a source - must disclose and, in most cases, decline

- Personal relationship with a source (romantic, close friendship) - prohibited unless fully disclosed and approved

How to Build a Policy That Actually Works

A policy that sits in a drawer is useless. The best ones are living documents. They’re reviewed yearly. They’re taught in onboarding. They’re discussed in editorial meetings.Here’s what works:

- Require disclosure before assignment. Not after. Not when someone catches you. Before you start writing. Every editor fills out a simple form: ‘Do you have any financial, personal, or professional ties to the subject of this story?’

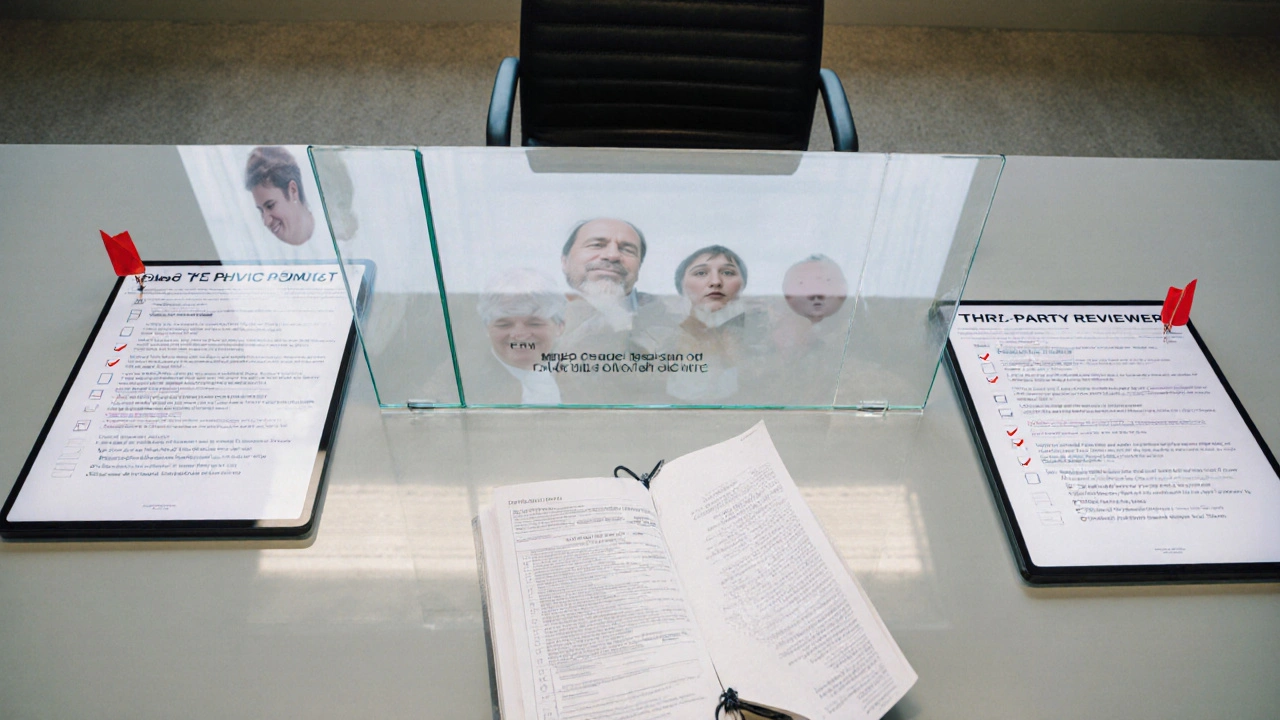

- Use a third-party reviewer. Have someone outside the story team check the disclosure form. Not your boss. Not your friend. Someone neutral.

- Make recusal the default. If there’s any doubt, the editor doesn’t write it. Another person does. No heroics. No ‘I can handle it.’

- Publicly disclose when possible. Add a short note at the bottom of the article: ‘Editor X previously consulted for Company Y.’ Transparency isn’t just ethical - it builds trust.

- Train new hires on real examples. Don’t just hand them a PDF. Show them the story that got pulled. Show them the apology. Show them the fallout.

At NPR, editors now complete a digital conflict form before each assignment. The system flags any match to known entities - companies, people, organizations. If there’s a hit, the editor can’t proceed without approval from the ethics team. It’s not perfect. But since 2021, internal disclosures have dropped by 42%. Why? Because people know they’ll be caught.

What Happens When You Ignore the Policy

There are consequences. Not just professional - personal.One editor at a regional newspaper wrote a glowing profile of a local tech founder. Later, it came out he’d been paid $5,000 for a consulting gig with the same company - a fact he never mentioned. The paper issued a correction. The editor resigned. But the real cost? The paper’s circulation dropped 18% over the next year. Readers didn’t just stop buying. They stopped believing anything the paper published.

And it’s not just about money. It’s about relationships. When a journalist is exposed for hiding a conflict, colleagues lose trust too. Newsrooms become quieter. People stop speaking up. Fear replaces accountability.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

In 2025, anyone can publish anything. Blogs, newsletters, TikTok explainers - no editor, no fact-checker, no policy. That makes the ones who still follow rules even more important.When you read a story from a trusted outlet, you’re not just reading facts. You’re trusting that someone else cared enough to check their own bias. That’s rare. And it’s valuable.

Conflict of interest policies aren’t about controlling editors. They’re about protecting the reader. They say: ‘We know you’re human. We know you have ties. But we won’t let those ties shape the truth.’

That’s not just good policy. It’s the only thing keeping journalism alive.

What counts as a conflict of interest for editors?

A conflict of interest is any personal, financial, or professional connection that could influence an editor’s judgment - even if they don’t realize it. This includes owning stock in a company they cover, having a family member employed by the subject of the story, having previously worked for the organization, accepting free travel or gifts from sources, or having a close personal relationship with a key person in the story. Most modern policies require disclosure or recusal for any of these situations.

Do editors have to disclose even small connections?

Yes. The trend in journalism is toward full transparency, not just avoiding obvious bribes. A past college friendship, a LinkedIn connection, or a single paid consultation can all be considered conflicts if they’re not disclosed. The goal isn’t to punish small ties - it’s to let readers decide if they trust the story. If the reader finds out later, the damage is worse than if the connection was revealed upfront.

Can an editor still write about a topic if they once worked there?

Most major news organizations prohibit editors from covering organizations they worked for within the last five years. Even if they left years ago, the risk of insider bias - or the perception of it - is too high. Some outlets allow it only with explicit approval and full disclosure. But the standard is to assign someone else. The story doesn’t lose value just because a different person writes it.

What happens if an editor hides a conflict?

If a conflict is discovered after publication, the story is usually retracted or corrected with a public note. The editor may face disciplinary action, including suspension or termination. Beyond professional consequences, the outlet’s credibility suffers. Readers lose trust, subscriptions drop, and it can take years to rebuild. In extreme cases, legal action or public boycotts follow.

Are conflict policies the same everywhere?

No. Big newsrooms like The Washington Post or BBC have detailed, enforceable policies with clear thresholds. Smaller outlets may have vague guidelines or none at all. Independent bloggers rarely have policies. But the industry standard is shifting toward stricter rules. Even smaller publications are adopting disclosure forms and recusal practices because readers expect it. What’s acceptable in one place isn’t acceptable in another - but the expectation of transparency is growing everywhere.

What Comes Next?

The next evolution won’t be more rules. It’ll be better tools. Some newsrooms are testing AI systems that scan editor bios and financial disclosures to flag potential conflicts before assignments are given. Others are building public dashboards where readers can see which editors have disclosed ties to which organizations.But the real change isn’t technological. It’s cultural. It’s about accepting that no one is perfectly neutral. And that’s okay - as long as you’re honest about it.

Journalism doesn’t need heroes. It needs people who admit when they’re not objective - and then step aside.