Wikipedia isn’t just a website. For millions of people in the Global South, it’s the only free, reliable source of knowledge they can access without a library, a university, or even stable internet. But who builds it? And how do they pay for it?

Who’s Writing Wikipedia in the Global South?

In Nigeria, a teacher named Amina uses her phone during lunch breaks to add local history entries about forgotten independence leaders. In Colombia, a group of university students runs monthly edit-a-thons to fix gaps in indigenous language articles. In Bangladesh, a retired librarian trains rural women to upload photos of traditional crafts to Commons - all without pay, and often without reliable electricity.

These aren’t outliers. Over 60% of Wikipedia’s active editors in low- and middle-income countries are women, youth, or members of marginalized communities. They’re not funded by tech giants. They’re not paid staff. They’re volunteers who show up because they know their culture, language, and history are missing from the world’s largest encyclopedia.

Where Does the Money Come From?

The Wikimedia Foundation, the nonprofit behind Wikipedia, receives most of its funding from small donations - about 85% from individuals worldwide. But for projects focused on the Global South, things get trickier. Grants from the Foundation are competitive, and many local groups struggle with paperwork, English-language applications, or bank accounts that accept international transfers.

Still, progress is happening. In 2024, the Wikimedia Foundation allocated over $12 million specifically to support chapters and user groups in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. That money went to things like: buying mobile data bundles for editors in remote villages, funding offline Wikipedia servers in schools without internet, and paying for translators to turn articles into local languages like Yoruba, Quechua, and Khmer.

Some funding comes from outside too. The Ford Foundation gave $2.5 million in 2023 to support African knowledge equity projects. UNESCO partnered with Wikimedia in 2024 to train 10,000 educators in 15 countries to use Wikipedia as a teaching tool. And in India, a local NGO called Knowledge for All a nonprofit that trains rural women to edit Wikipedia in regional languages raised $800,000 through crowdfunding to run 200 edit-a-thons across seven states.

What Happens at These Events?

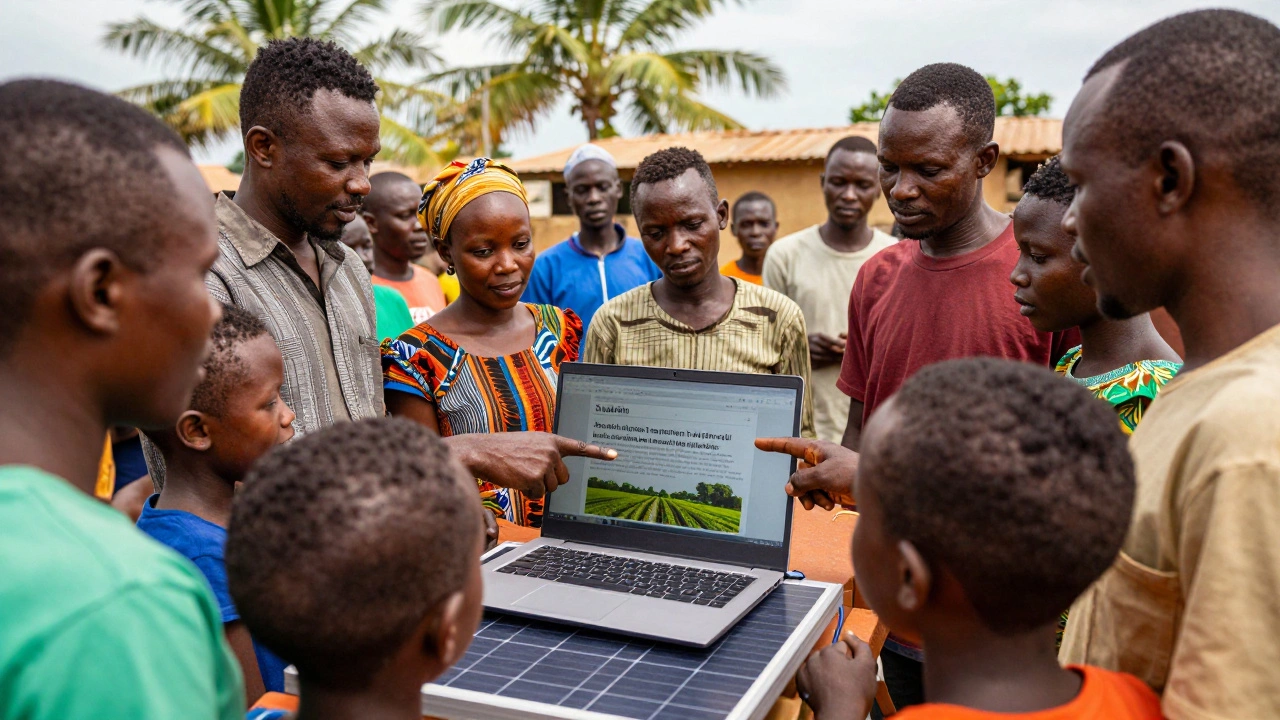

Events aren’t just about editing. They’re about community. In Ghana, the Wikipedia Africa a volunteer-led network of editors across 20 African countries hosts "Knowledge Cafés" - open-air gatherings where people bring questions about their local history, and volunteers look up answers together on a single laptop powered by a solar panel.

In Peru, the Quechua Wikipedia Project a grassroots effort to expand content in the most spoken indigenous language in the Americas runs workshops in highland villages where elders dictate oral histories, and teens type them into Wikipedia using tablet computers donated by a university.

These events have real impact. Since 2021, the number of articles in Swahili Wikipedia has more than doubled - from 45,000 to over 98,000. In Hindi, over 30,000 new articles were added in 2024 alone, mostly about local festivals, folk medicine, and regional agriculture. And in the Philippines, the Waray Wikipedia project now has more articles than the Tagalog version in some niche categories like traditional weaving patterns and indigenous plants.

Why This Matters Beyond Wikipedia

When a farmer in Zambia looks up how to treat a sick goat, and finds a detailed guide written in Nyanja by someone from her village, that’s not just information. It’s dignity. It’s validation. It’s proof that her knowledge matters.

These initiatives challenge the idea that knowledge belongs only to institutions in the Global North. They prove that people in villages, slums, and remote towns can build something as massive and trusted as Wikipedia - using nothing but their phones, their passion, and each other.

And it’s not just about content. It’s about power. When women in Pakistan edit articles about female scientists from their own region, they’re rewriting who gets remembered. When Indigenous youth in Bolivia add maps of ancestral lands to Wikipedia, they’re reclaiming territory that governments erased from official records.

What’s Still Missing?

Despite the progress, big gaps remain. Only 1.4% of Wikipedia’s total content is in African languages - even though Africa has over 2,000 languages. Less than 5% of editors in the Global South are over 50. Many local organizations still can’t access grants because they don’t have formal nonprofit status. And in places like Haiti and Sudan, conflict and internet shutdowns make editing nearly impossible.

There’s also a lack of tech support. Most Wikipedia tools are built for English speakers with fast internet. Mobile editing is clunky. Uploading photos from low-bandwidth areas takes forever. And translation tools often fail with tonal languages or non-Latin scripts.

How You Can Help - Even From Afar

You don’t need to fly to Nairobi or Jakarta to help. Here’s what actually works:

- Donate to the Wikimedia Foundation the nonprofit that supports Wikipedia and its global volunteer communities and choose to fund Global South initiatives.

- Join a global edit-a-thon - many are held online and welcome beginners.

- Translate a single article from English into your native language - even one helps.

- Share Wikipedia articles written by Global South editors. Give them visibility.

- If you’re a teacher, librarian, or community leader: encourage your students or neighbors to contribute. Start small. One article. One photo.

Knowledge isn’t neutral. It’s shaped by who gets to write it. Right now, the Global South is writing its own story - slowly, stubbornly, and beautifully. And it needs more hands.

How do Wikipedia editors in the Global South get paid?

Most Wikipedia editors in the Global South are unpaid volunteers. Some receive small stipends or grants from the Wikimedia Foundation or partner organizations to cover data costs, event supplies, or travel to in-person meetups. But no one gets a salary for editing. The work is driven by community, not money.

Can I contribute to Wikipedia if I don’t speak English?

Absolutely. Wikipedia exists in over 300 languages, and many of the fastest-growing projects are in languages like Bengali, Swahili, and Tamil. You can edit in your native language - no English needed. The platform supports most writing systems, and tools like the Content Translation feature help you start from existing articles.

Are there any risks for editors in certain countries?

Yes. In some countries, editing topics related to politics, religion, or human rights can lead to harassment, censorship, or legal trouble. Wikimedia provides safety guidelines and anonymous editing options. Many editors use VPNs or edit from public libraries. The Wikimedia Foundation also has a Trust & Safety team that supports editors under threat.

How can I find Wikipedia events near me?

Visit the Wikimedia Events Calendar at meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Events. You can filter by region, language, or topic. Many events are virtual and open to anyone. Local chapters in Africa, Latin America, and Asia often post updates on Facebook, WhatsApp, or Telegram groups - search for "Wikipedia [your country]".

Why isn’t more Wikipedia content in African languages?

There are over 2,000 languages spoken in Africa, but only about 150 have Wikipedia pages - and most have fewer than 10,000 articles. The main barriers are lack of digital tools for less common scripts, few trained editors, and limited funding. But projects like the Yoruba Wikipedia initiative and the Amharic Language Lab are changing that, one article at a time.

What Comes Next?

The next five years will be critical. With AI tools becoming more common, there’s a real risk that Wikipedia’s human-edited content gets drowned out by machine-generated summaries - especially in languages with little digital presence. But the Global South community is fighting back. They’re building AI training datasets from their own Wikipedia content. They’re demanding that AI companies pay for data used to train models - data that came from their unpaid labor.

It’s not just about keeping Wikipedia alive. It’s about protecting the idea that knowledge should be free, local, and built by the people who live it.