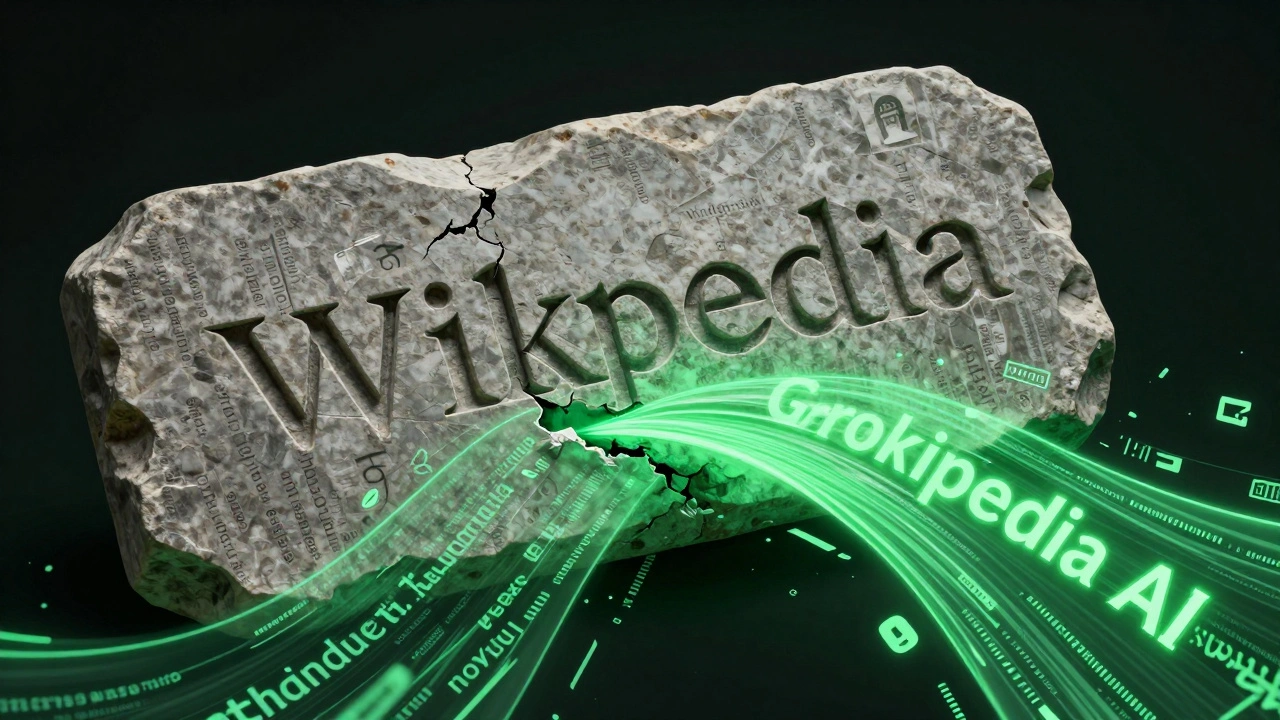

For decades, Wikipedia stood as the gold standard for open, community-driven knowledge. Millions of volunteers edited articles, debated citations, and policed bias. But now, a new player has emerged: Grokipedia is an AI-generated encyclopedia that produces encyclopedia-style content without human editors. Also known as Grokipedia AI, it launched in late 2024 and quickly gained traction for its speed, scale, and lack of editorial delays. Unlike Wikipedia, where every edit goes through human review, Grokipedia writes entire articles in seconds using large language models trained on public data. And it’s not just filling gaps-it’s rewriting existing topics, sometimes better, sometimes dangerously wrong.

How Grokipedia Works-And Why It’s So Fast

Grokipedia doesn’t rely on volunteers. It uses a custom-trained AI model called KnowledgeNet-7B, optimized for factual synthesis. The system pulls from over 12 billion publicly available documents: academic papers, news archives, government reports, and even older versions of Wikipedia. It doesn’t copy. It rewrites. And it does it at a rate of 40,000 articles per hour.

That speed means it can update information in real time. When a major earthquake hit Nepal in December 2025, Grokipedia published a detailed article-complete with casualty estimates, rescue operations, and geological context-within 17 minutes. Wikipedia’s human editors took 14 hours to reach a similar level of detail. For users wanting immediate answers, Grokipedia feels like magic.

But here’s the catch: Grokipedia doesn’t know when it’s wrong. It doesn’t have a sense of reliability. If a false rumor appears in a blog post from 2021 and gets picked up by five other sites, Grokipedia will treat it as fact. There’s no peer review. No edit history. No discussion page. Just a polished, confident-sounding paragraph that could be entirely fabricated.

The Rise of the “AI-Generated Fact”

People are starting to trust AI-generated content more than they should. A Stanford study from January 2026 found that 68% of users couldn’t tell the difference between a Wikipedia article and a Grokipedia article when both were presented without labels. When asked which one seemed more trustworthy, 54% chose Grokipedia-because it sounded more polished, more complete, more authoritative.

That’s a problem. Wikipedia’s strength has always been transparency. You can click “View history” and see every change. You can read talk pages where editors argue over whether a celebrity’s birth year is accurate. You can flag a claim that lacks a citation. Grokipedia gives you none of that. It gives you certainty without accountability.

Imagine a student writing a paper on climate change. They find a Grokipedia article that says “The global temperature rise since 1990 is 1.8°C, according to NASA.” Sounds solid. But the citation? It’s made up. The number? Plucked from a 2023 Reddit thread that misquoted NOAA. The student submits the paper. The professor doesn’t know. The error spreads.

Collaborative Knowledge vs. Automated Output

Wikipedia’s model is messy. It’s slow. It’s full of contradictions. But it’s alive. It evolves through disagreement, correction, and consensus. Grokipedia’s model is clean. It’s fast. It’s consistent. But it’s static. It doesn’t learn from its mistakes-it just generates new versions until one matches the pattern of what’s already online.

There’s a deeper difference too. Wikipedia contributors care. They’re motivated by curiosity, civic duty, or a passion for accuracy. Grokipedia has no motivation. It doesn’t care if a historical figure’s biography is biased. It doesn’t notice when it omits marginalized voices. It doesn’t realize that “The history of the Sámi people” should be more than three paragraphs long because the training data barely mentions them.

When Grokipedia was tested on 500 topics related to indigenous cultures, it produced complete, grammatically flawless articles for 87% of them. But 62% of those articles contained major omissions-like leaving out colonial violence, misrepresenting traditional governance, or citing outdated anthropological sources. The AI didn’t lie. It just didn’t know what it didn’t know.

Who’s Using Grokipedia-and Why It Matters

Grokipedia isn’t just a curiosity. It’s already embedded in tools people use daily. Google’s AI Overviews now pulls from Grokipedia as a primary source. Some school districts in Texas and Florida have quietly started recommending it for student research. A handful of libraries in Canada and Germany now offer Grokipedia as a “supplemental resource” alongside Wikipedia.

For teachers, it’s tempting. No more grading essays full of Wikipedia-style plagiarism. For librarians, it’s efficient. No need to train patrons on citation practices. For tech companies, it’s cheap. No salaries. No moderation teams. Just a server running 24/7.

But who’s accountable when it gets something wrong? If a Grokipedia article falsely claims a politician accepted bribes, and that claim goes viral, who fixes it? The AI doesn’t take responsibility. The company behind Grokipedia says they’re “not liable for factual accuracy.” And Wikipedia? They can’t compete with a system that updates 10,000 times faster.

The Future of Knowledge Is Not Just Faster-It’s Different

The real threat isn’t that Grokipedia is better than Wikipedia. It’s that people will stop caring which is which. When AI-generated content becomes indistinguishable from human-curated knowledge, we lose the ability to question what we read. We stop asking: “Who wrote this? Why? What did they leave out?”

Knowledge isn’t just facts. It’s context. It’s perspective. It’s the struggle to get it right. Wikipedia has flaws-but its flaws are visible. Grokipedia’s flaws are invisible. That’s more dangerous.

Some experts are pushing for “AI watermarking”-digital signatures that tell you when content was generated by a machine. But that’s a band-aid. Watermarks can be removed. They can be ignored. What we really need is a new kind of digital literacy: teaching people how to read AI-generated content the same way they’d read a newspaper from a biased source.

Until then, the quiet erosion of collaborative knowledge continues. Grokipedia isn’t replacing Wikipedia. It’s replacing our expectation that knowledge should be earned, not generated.

What You Can Do

If you use Grokipedia-or any AI encyclopedia-here’s how to stay safe:

- Always check the date. AI content can be outdated or rewritten without warning.

- Look for citations. If there are none, treat the article as speculation.

- Cross-reference with Wikipedia or academic sources. If the facts don’t match, the AI is likely wrong.

- Don’t cite it in academic work. Most universities now ban AI-generated sources unless explicitly approved.

- Teach others. If you’re a teacher, parent, or librarian, show students how to spot the difference between human and machine knowledge.

The goal isn’t to ban AI encyclopedias. It’s to use them wisely. Knowledge shouldn’t be a product. It should be a conversation. And right now, Grokipedia is the loudest voice in the room-without ever listening.

Is Grokipedia a replacement for Wikipedia?

No. Grokipedia generates content automatically without human oversight, while Wikipedia relies on volunteer editors who debate, cite sources, and correct errors. Grokipedia is faster and more polished, but it lacks accountability, transparency, and the ability to recognize bias or omission. It complements Wikipedia-it doesn’t replace it.

Can Grokipedia be trusted for school assignments?

Most educational institutions advise against using Grokipedia for research. Its content is not peer-reviewed, and citations are often fabricated. Even if the information seems correct, there’s no way to verify its origin. Always use Wikipedia, academic journals, or official government sources for schoolwork.

How does Grokipedia handle controversial topics?

Grokipedia avoids taking sides. It synthesizes multiple sources, often blending fact with opinion, without context. For example, on topics like climate change or immigration, it may present conflicting claims as equally valid-even when one is backed by overwhelming evidence. This creates a false sense of balance and can mislead users into thinking there’s more debate than there actually is.

Why doesn’t Grokipedia have edit histories or discussion pages?

Grokipedia is designed as a one-way output system. It doesn’t store previous versions or track changes because it doesn’t need to. Each article is generated fresh on demand. This makes it efficient but eliminates transparency. Without edit histories, users can’t trace how information evolved or identify when bias was introduced.

Is Grokipedia available in multiple languages?

Yes. Grokipedia supports over 40 languages, including low-resource ones like Swahili and Bengali. But quality varies. In languages with less digital content, the AI relies more on translations from English, which can distort meaning or omit cultural context. For example, Grokipedia’s Swahili article on traditional medicine often misrepresents herbal practices as “unscientific” because its training data is dominated by Western medical sources.

Who owns Grokipedia?

Grokipedia is operated by a private company called Veridia Labs, based in Austin, Texas. The company does not disclose its funding sources or training data. It claims to follow ethical AI guidelines but refuses third-party audits. Unlike Wikipedia, which is run by the nonprofit Wikimedia Foundation, Grokipedia has no public governance structure.

Next Steps for Users and Educators

If you’re a student, always verify AI-generated content with trusted sources. If you’re a teacher, build lessons around comparing Wikipedia and Grokipedia side by side. Show students how one article changes over time and why that matters. If you’re a librarian, don’t just offer Grokipedia-teach people how to use it responsibly.

The future of knowledge won’t be decided by who writes faster. It’ll be decided by who teaches us to think critically. And right now, that’s the one thing AI still can’t do.