Wikipedia doesn’t just sit there waiting for the future to happen. It’s actively reshaping how knowledge survives in the age of artificial intelligence. The Wikimedia Foundation, the nonprofit behind Wikipedia and its sister projects, isn’t just watching as AI companies scrape its content-they’re fighting back with clear rules, public pressure, and legal strategy. This isn’t about stopping AI. It’s about making sure the foundation of free knowledge isn’t erased, exploited, or rewritten without permission.

AI is training on Wikipedia, but not paying for it

Every day, AI models like those from OpenAI, Google, and Meta ingest billions of text snippets. A huge chunk of that data comes from Wikipedia. Why? Because it’s free, structured, and reliable. Over 200 million people use Wikipedia every month. Its articles are written in plain language, edited by volunteers, and updated constantly. That makes it perfect training material for AI systems trying to understand how humans write and think.

But here’s the problem: Wikipedia doesn’t get paid. Its contributors don’t get credit. And the Foundation doesn’t control how that content gets used. Some AI companies even sell products built on Wikipedia’s knowledge without ever asking. That’s not how the open knowledge model was meant to work.

In 2023, the Wikimedia Foundation published a report showing that over 70% of the top 100 AI training datasets included Wikipedia content. Not one of them had obtained a license. Not one gave attribution. The Foundation called it a violation of the Creative Commons license that protects Wikipedia’s text. And they weren’t just upset-they started taking action.

Wikipedia’s license isn’t optional

Wikipedia content is published under CC BY-SA 4.0. That means anyone can use it, even commercially, as long as they give credit and share any new work under the same terms. But most AI companies ignore that. They don’t label the source. They don’t link back. They don’t open their models to public inspection.

That’s not just rude-it’s illegal. The Wikimedia Foundation has made it clear: if you use Wikipedia to train your AI, you must comply with the license. That means proper attribution, sharing derivative works under the same license, and not hiding the source behind proprietary walls.

Some companies have started to comply. Meta, for example, released a version of its Llama model that includes a list of training sources, including Wikipedia. It’s not perfect, but it’s a step. Others? Still silent.

The Foundation doesn’t have the resources to sue every tech giant. But they don’t need to. They’re using public pressure. Every time a major AI company is caught using Wikipedia without credit, the Foundation publishes a public statement. Journalists pick it up. Users tweet about it. And suddenly, those companies have to answer.

They’re building tools to track AI misuse

Instead of just complaining, the Wikimedia Foundation is building tools to fight back. In 2024, they launched the Wikimedia AI Audit Project. It’s a public, open-source system that scans AI-generated text for patterns that match Wikipedia’s writing style, structure, and phrasing.

The tool doesn’t claim to catch every instance. But it’s already flagged over 12,000 AI-generated summaries that closely mirror Wikipedia articles-without attribution. The data is public. Anyone can check it. Researchers, journalists, and even users can report suspicious outputs.

It’s not about banning AI. It’s about transparency. If an AI says something that sounds like Wikipedia, users should know. And if that AI was trained on Wikipedia, the public should know that too.

They’re pushing for legal change

Copyright law wasn’t built for AI. Most countries still treat AI-generated text as having no copyright owner. That means no one can sue an AI company for copying Wikipedia-even if they used millions of articles without permission.

The Wikimedia Foundation is lobbying governments to fix this. In the U.S., they’ve submitted formal comments to the Copyright Office. In the EU, they’re working with lawmakers on the AI Act. Their ask is simple: if you train on copyrighted material, you must disclose it. And if you profit from it, you must compensate the source.

They’re not asking for royalties. They’re asking for honesty. For attribution. For the same rules that apply to textbooks, news articles, and academic papers to apply to AI too.

And it’s working. In late 2024, the European Parliament added a new clause to the AI Act requiring transparency about training data sources. While not perfect, it’s the first time a major regulatory body has forced AI companies to name their sources. The Wikimedia Foundation helped write that clause.

Volunteers are the real defense

Behind every Wikipedia article is a volunteer. Someone who spent hours checking sources, rewriting sentences, and fighting vandalism. These aren’t employees. They’re teachers, students, librarians, and retirees. They do this because they believe knowledge should be free-and fair.

When AI copies Wikipedia without credit, it’s not just stealing words. It’s stealing their work. And volunteers are speaking up. In 2024, over 1,500 editors signed an open letter demanding AI companies respect copyright. Some even created their own tools to detect AI-generated plagiarism on Wikipedia pages.

One editor from Germany built a browser extension that highlights text on websites that matches Wikipedia’s phrasing. Another from Canada created a bot that automatically flags AI-generated summaries in Wikipedia talk pages. These aren’t fancy startups. They’re ordinary people using code to protect what they care about.

What’s next for open knowledge?

The Wikimedia Foundation isn’t trying to stop AI. They’re trying to make sure AI doesn’t kill the open web. Their goal is simple: if AI uses Wikipedia, it must give back. Not with money, but with openness.

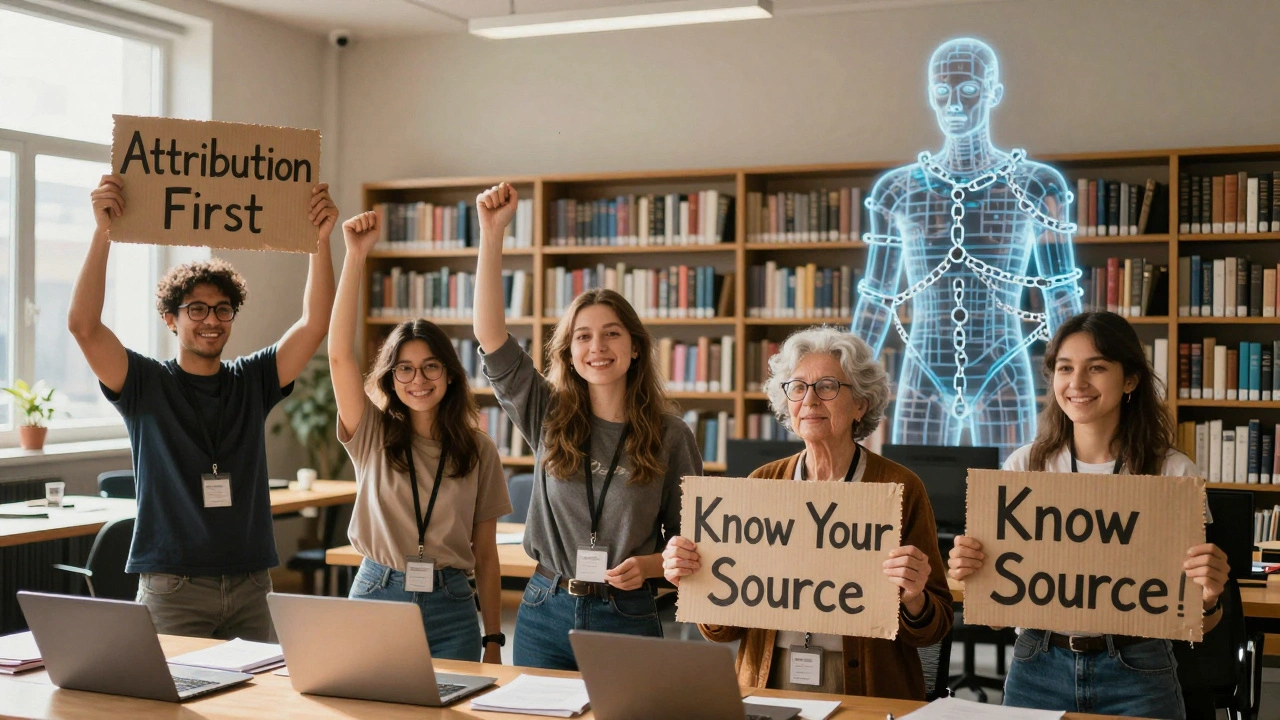

They’re pushing for a new standard: Attribution First. Any AI system that uses free knowledge must clearly say where it came from. And any company that profits from it must let others use their model under the same open terms.

That’s the future they’re building. Not a world where AI replaces Wikipedia. But one where AI respects it.

Wikipedia’s future isn’t written by algorithms. It’s written by people. And the Foundation is making sure those people still have a voice.

Does the Wikimedia Foundation own Wikipedia’s content?

No. The Wikimedia Foundation doesn’t own Wikipedia’s content. Every article is written and edited by volunteers. The content is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike (CC BY-SA 4.0), which means anyone can use it as long as they give credit and share any new work under the same license. The Foundation only provides the infrastructure and legal support to keep Wikipedia running.

Can AI companies legally use Wikipedia to train their models?

Technically, yes-if they follow the CC BY-SA 4.0 license. That means they must clearly credit Wikipedia as the source and release any derivative works under the same open license. Most AI companies don’t do this. They use Wikipedia’s content without attribution or sharing their models openly, which violates the license. The Wikimedia Foundation considers this misuse and is taking steps to enforce compliance.

Why doesn’t the Wikimedia Foundation just charge AI companies for access?

The Foundation’s mission is to make knowledge freely available to everyone. Charging for access would go against that principle. Instead, they’re asking for compliance with the existing open license: attribution and openness. They believe knowledge should be shared, not locked behind paywalls-even when used by powerful corporations.

What happens if an AI company ignores the Wikimedia Foundation’s requests?

The Foundation doesn’t have the budget to sue every company. Instead, they use public pressure. They publish reports, issue statements, and work with journalists to expose violations. In some cases, they’ve worked with legal experts to file formal complaints with regulatory agencies. Public backlash has already forced companies like Meta to adjust their practices.

Is Wikipedia’s content being replaced by AI-generated summaries?

Yes, in some places. Search engines and AI assistants often pull from Wikipedia to generate quick answers, but they rarely link back. This reduces traffic to Wikipedia and makes it harder for volunteers to know what’s being read or edited. The Foundation is fighting this by building detection tools and pushing for transparency so users know when they’re seeing AI-generated text versus human-edited content.