Most people think of Wikipedia as the go-to source for quick facts. But behind every article, there’s something quieter, more powerful, and far more useful: Wikidata is a free, collaborative, multilingual knowledge base that stores structured data used by Wikipedia and thousands of other projects worldwide. Also known as Wikidata Project, it was launched in 2012 and now holds over 110 million items, each with precise identifiers, relationships, and verified values. Unlike Wikipedia’s free-form text, Wikidata turns facts into data you can ask questions of - like a database built by millions of volunteers.

What makes Wikidata different from Wikipedia?

Wikipedia tells you what something is. Wikidata tells you how it connects to everything else. If you read that Leonardo da Vinci was born in 1452 on Wikipedia, that’s a sentence. On Wikidata, that’s a structured fact: Leonardo da Vinci (Q503) has the property date of birth (P569) with the value 1452. That’s not just text - it’s a machine-readable node in a global network.

This structure lets computers understand relationships. For example, Wikidata knows that:

- Leonardo da Vinci (Q503) is a human (Q5)

- Leonardo da Vinci (Q503) has occupation painter (Q1267148) and inventor (Q163455)

- Leonardo da Vinci (Q503) was born in Vinci, Italy (Q1459)

- Vinci, Italy (Q1459) is located in Tuscany (Q183051)

These aren’t just links. They’re triples - subject-predicate-object - that let software build graphs. You can ask: Which painters were born in Italy before 1500? and get a list generated automatically. No manual searching. No broken links. Just data.

How Wikidata turns facts into fuel for AI

Large language models like GPT or Claude read text. They guess answers based on patterns. But they often hallucinate - inventing facts that sound right but aren’t true. Wikidata fixes that. It’s the source of truth behind many AI systems that need accurate, up-to-date data.

Companies like Google, Microsoft, and Meta use Wikidata to power their knowledge panels, search suggestions, and chatbot responses. Why? Because Wikidata is updated in real time by editors worldwide. If a new president is elected, someone adds it to Wikidata within hours. Within minutes, AI assistants start giving correct answers.

It’s not just big tech. Researchers at universities use Wikidata to track scientific citations, map disease outbreaks, or trace the spread of cultural trends. A 2024 study from the University of Oxford showed that AI systems using Wikidata as a knowledge source had 37% fewer factual errors than those relying only on web-scraped text.

How anyone can contribute - no coding needed

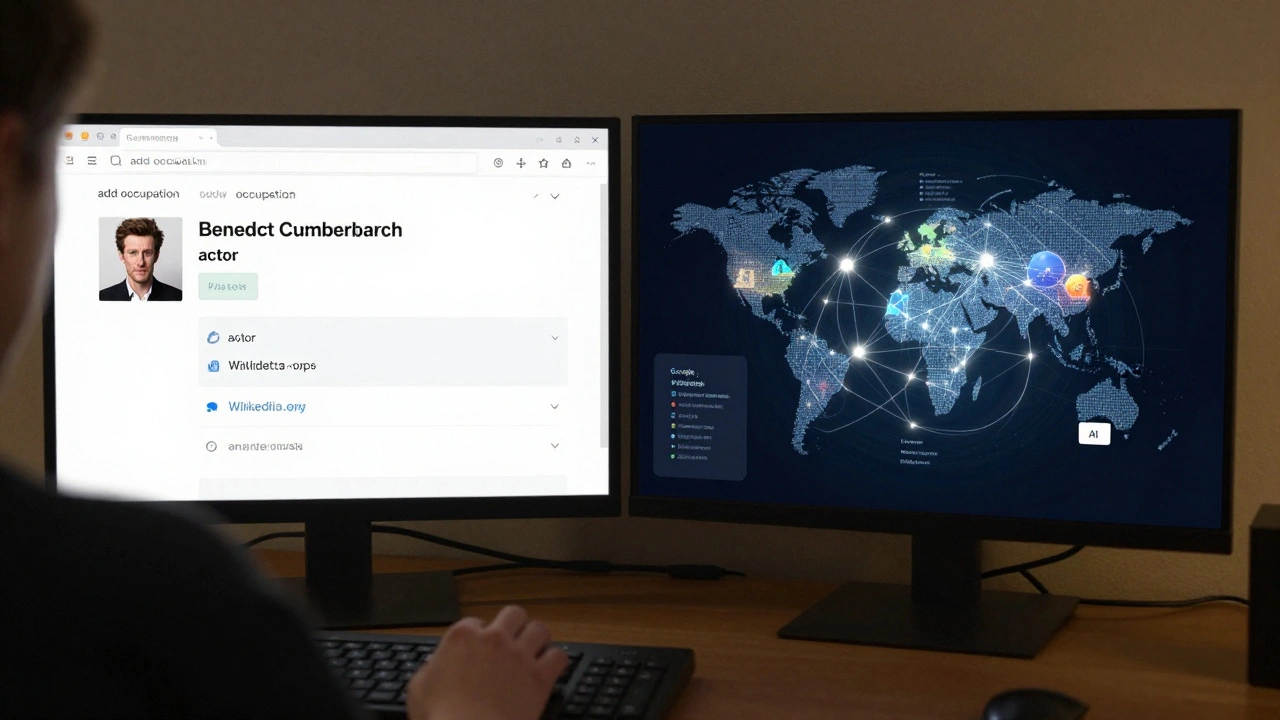

You don’t need to be a programmer to help build this encyclopedia. Wikidata’s interface is designed for regular people. If you know that the actor who played Sherlock Holmes in the 2010 BBC series is Benedict Cumberbatch, you can add that fact.

Here’s how it works:

- Go to wikidata.org and search for "Benedict Cumberbatch".

- If he’s not there, create a new item.

- Find the property "instance of" and select "human".

- Add "occupation" → "actor".

- Add "portrayed" → "Sherlock Holmes" (linking to the character’s item).

- Save. Done.

That’s it. One person, five minutes, and now that fact is available to every app, website, and AI system that pulls from Wikidata. There are over 10,000 active editors just like you, fixing errors, adding details, and connecting dots across languages and cultures.

The scale: 110 million items and counting

Wikidata doesn’t just hold people and places. It holds:

- Over 8 million chemical compounds

- 1.5 million artworks

- 400,000 films

- 2 million species

- 700,000 musical compositions

Each one has a unique ID (like Q12345), properties (like "inception," "author," "material"), and qualifiers (like "start time," "end time," "source").

Compare that to traditional encyclopedias: Britannica has around 120,000 entries. Wikipedia has over 60 million articles - but they’re all text. Wikidata turns a fraction of that into structured, reusable data. And it’s growing faster than any other knowledge base in history.

Why this matters for the future of knowledge

We’re moving from a world where knowledge is stored in books and websites to one where it’s stored in interconnected graphs. Wikidata is the foundation of that shift.

Imagine asking your smart speaker: "What’s the average life expectancy of people born in the same year as Marie Curie?" - and it answers correctly, pulling data from Wikidata, cross-referencing birth records, mortality rates, and geographic data. That’s not science fiction. It’s already possible.

Libraries, museums, and schools are starting to use Wikidata to digitize their collections. The British Museum linked 120,000 artifacts to Wikidata. The Smithsonian added 3 million records. Now, anyone can explore those artifacts alongside historical figures, locations, and materials - all in one searchable graph.

This isn’t about replacing Wikipedia. It’s about making it smarter. Every edit on Wikidata improves every Wikipedia article, every search result, every AI response. It’s the silent engine behind the future of knowledge.

What Wikidata can’t do - and why that’s okay

Wikidata isn’t perfect. It doesn’t cover every obscure fact. Some items are incomplete. Some data is outdated. It doesn’t include opinions, interpretations, or subjective analysis - only verifiable, measurable facts.

That’s intentional. Wikidata avoids bias by requiring sources. If you add that someone was "the greatest artist ever," it gets rejected. But if you add that they won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1989, and cite the official announcement, it stays.

This makes it less flashy than Wikipedia - but far more reliable. It’s not meant to be read by humans. It’s meant to be used by machines. And that’s where its power lies.

How you can start using Wikidata today

You don’t need to be a researcher or coder to benefit from Wikidata. Here are simple ways to use it:

- Use the Wikidata Query Service to run your own queries. Type: "Show me all female scientists born in Poland" - and get a list.

- Install browser extensions like "Wikidata Toolkit" to see structured data behind Wikipedia pages.

- Contribute one fact. Even if it’s just adding a birthdate or a country.

- Use Wikidata IDs in your own projects. Developers can pull data via API - no need to scrape Wikipedia.

Wikidata is open. It’s free. It’s built by people like you. And it’s the closest thing we have to a true machine-readable encyclopedia of everything.

Is Wikidata the same as Wikipedia?

No. Wikipedia is a collection of human-written articles in natural language. Wikidata is a structured database of facts - numbers, dates, relationships - designed for machines. Wikipedia uses Wikidata to auto-fill infoboxes and keep data consistent across languages.

Can I trust Wikidata’s data?

Yes, if it has a source. Every fact in Wikidata must be backed by a reliable reference - a book, official website, academic paper, or reputable news outlet. Edits without sources are flagged and often removed. It’s not perfect, but it’s more transparent than most databases.

Do I need to know how to code to use Wikidata?

No. You can browse, search, and edit Wikidata with a web browser. If you want to run advanced queries or pull data into apps, you’ll need basic technical skills - but most users just contribute facts or use tools built on top of it.

How often is Wikidata updated?

Every few seconds. Changes made by editors appear instantly. That’s why it’s so powerful - when a new country is recognized or a celebrity passes away, Wikidata updates faster than most news sites. It’s the most up-to-date knowledge base on the planet.

Why doesn’t Google just use its own database?

Because Wikidata is open and community-driven. Google could build its own database, but it would cost millions and take years. Wikidata already exists, is constantly updated by volunteers, and covers more ground than any single company could manage. Google uses it because it’s better than anything they could build alone.