Wikipedia doesn’t update like a typical app. There’s no ‘Update Now’ button. No sprint cycles. No product managers pushing features because they think users ‘will love it.’ Instead, every change-big or small-goes through a slow, open, and often messy process designed to protect the integrity of the world’s largest free encyclopedia. If you’ve ever wondered why a new editing tool takes months to appear, or why a controversial UI tweak got rolled back, the answer isn’t bureaucracy. It’s prioritization. And it’s built into Wikimedia’s DNA.

Features Don’t Get Built Because They’re Cool

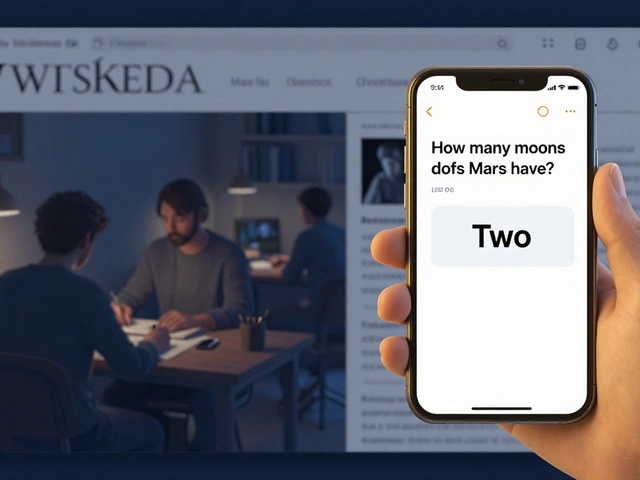

At most tech companies, new features are born from user surveys, A/B tests, or executive gut feelings. At Wikimedia, the bar is higher. A feature must solve a real problem for editors-people who actually maintain Wikipedia’s content. That means if 10,000 readers want a dark mode, but only 300 active editors say it’s slowing them down, dark mode won’t be a priority. The focus isn’t on growth or engagement. It’s on sustainability.

Take the VisualEditor, for example. Launched in 2013, it was meant to let people edit Wikipedia without learning wikitext. Sounds great, right? But early adoption was terrible. Experienced editors hated it. It broke citations. It corrupted templates. It added 30% more time to simple edits. Instead of pushing harder, the Wikimedia Foundation paused the rollout. They went back to the community. They rebuilt it from the ground up, with editors leading the design. It took five years. But today, over 70% of new edits on English Wikipedia use VisualEditor. Why? Because it was built with the people who keep Wikipedia alive, not the people who just visit it.

The Three Filters: Impact, Feasibility, and Alignment

Every proposed feature goes through three filters before it even gets a development slot.

- Impact: Will this help hundreds or thousands of editors? Or just a handful? A tool that helps bot operators automate copyright checks might help 50 people-but those 50 are responsible for removing 20,000 violations a month. That’s high impact. A button that changes font size? Low impact.

- Feasibility: Can this be built without breaking existing systems? Wikipedia runs on 20-year-old code that still works. Adding a flashy new feature that requires rewriting half the backend? Not happening. The team favors incremental changes that layer on top of existing infrastructure. For example, the new Citation Tool didn’t replace the old citation system. It just made it easier to use.

- Alignment: Does this fit Wikimedia’s mission? No ads. No tracking. No monetization. If a feature feels like it’s pushing toward commercialization-even subtly-it gets rejected. A proposal to add ‘sponsored article’ badges? Dead on arrival. A proposal to improve accessibility for blind editors? Top priority.

These filters aren’t theoretical. They’re documented in the Product Prioritization Framework, a public document updated quarterly. Anyone can read it. Anyone can comment. And they do-hundreds of times a month.

The Role of the Community: Editors as Product Managers

Wikipedia’s product team doesn’t have a single product manager. They have 30 million editors.

Every major feature starts as a discussion on a talk page. Someone notices that citing sources on mobile is broken. They post a suggestion on the Wikipedia:VisualEditor/Feedback page. Others chime in. Some say, “I’ve had this problem too.” Others say, “This will make vandalism easier.” A volunteer developer might pick it up and build a prototype. Then it goes to a beta feature-a testing environment where only a few thousand editors can try it.

That’s the critical step. Beta features aren’t hidden. They’re public. You can opt in. You can opt out. You can report bugs. You can argue about design. And if enough editors say, “This makes things worse,” the feature gets pulled-even if it’s been coded for six months.

That’s how the Page Curation tool for patrolling new articles was killed in 2021. It looked sleek. It automated flagging. But editors found it was mislabeling legitimate edits as vandalism. The community pushed back. The team listened. The tool was archived. No apology. No press release. Just a quiet update on the wiki: “We’re not moving forward with this.”

How Long Does It Take? Real Timelines

Don’t expect fast. Here’s how long real changes take:

- Minor UI tweak (e.g., button color change): 2-6 weeks

- New editing tool (e.g., improved reference manager): 6-18 months

- Major infrastructure change (e.g., switching from MySQL to MariaDB): 2-4 years

- Global feature rollout (e.g., new mobile interface): 3-5 years

Why so long? Because every change has to work across 300+ language editions. A feature that works perfectly in English might crash in Bengali because of right-to-left text rendering. Or it might conflict with a custom template used by 20,000 editors in German Wikipedia. Testing isn’t done in a lab. It’s done in the wild, by real users, over months.

One example: the Structured Data on Commons project. It began in 2016 to let users add machine-readable tags to images on Wikimedia Commons. By 2024, it was live on over 80 languages. But it took eight years. Why? Because every language community had to agree on how to label “type of tree,” “historical period,” or “artist.” No single team could decide that. The community had to build consensus. That’s not inefficient. That’s intentional.

What Gets Prioritized Now? (2026 Edition)

As of early 2026, the top three priorities are:

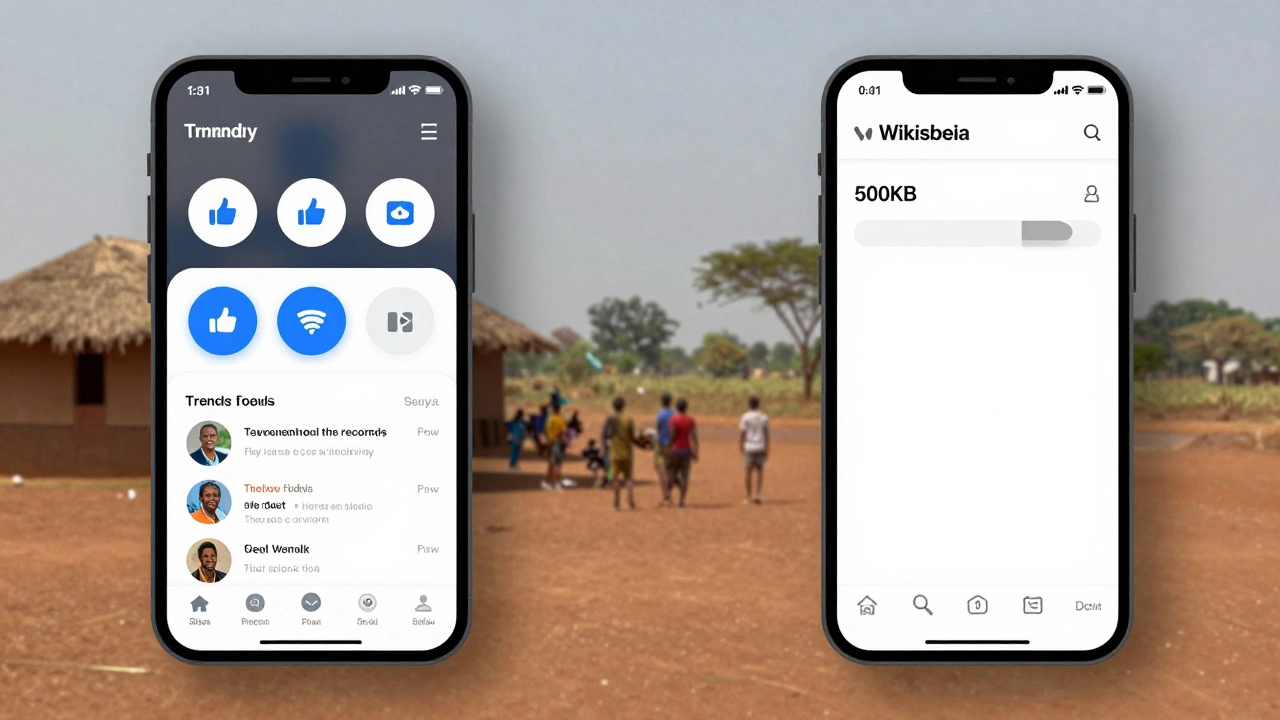

- Mobile editing improvements: Over 60% of edits now come from phones. But the mobile editor still feels clunky. The team is rebuilding it from scratch with input from editors in Nigeria, India, and Brazil.

- AI-assisted editing tools: Not to replace humans, but to help. Tools that suggest citations, flag potential bias, or detect vandalism using open-source models-trained on public Wikipedia data, not private datasets.

- Accessibility for low-bandwidth regions: In parts of Africa and Southeast Asia, many users still edit on 2G networks. New features must load under 500KB. That means stripping out animations, compressing fonts, and even simplifying the interface.

Notice what’s missing? No “personalized feed.” No “trending topics.” No “like” buttons. Those would turn Wikipedia into a social platform. And that’s not the goal.

Why This System Works

Wikipedia is the 7th most visited website in the world. It’s edited by volunteers. It’s free. It’s mostly accurate. And it hasn’t been broken by ads, algorithms, or corporate pressure.

That’s not luck. It’s the result of a product process that puts the community first-not as users, but as co-owners. Every feature is tested by the people who know the content best. Every decision is public. Every failure is documented. And every success is earned, not bought.

Most tech companies chase growth. Wikimedia chases trust. And that’s why, even in 2026, when every other platform is chasing AI and attention, Wikipedia still works.

Why doesn’t Wikimedia just hire more developers to speed up feature rollouts?

Wikipedia’s codebase is over 15 million lines of code, and most of it is maintained by volunteers. Hiring more staff wouldn’t fix the bottleneck-the bottleneck is consensus. Even with 100 developers, a feature still needs approval from thousands of editors across dozens of languages. Speed isn’t the goal. stability is.

Can anyone suggest a feature for Wikipedia?

Yes. Anyone can propose a feature on any Wikipedia talk page, the Wikimedia Phabricator system, or the Product and Technology newsletter. Proposals are reviewed publicly. Many top features started as random comments from anonymous editors. One of the most-used citation tools began as a post on a French Wikipedia forum in 2014.

Do corporate sponsors influence what features get built?

No. Wikimedia Foundation’s funding comes from individual donations, not corporations. While some partners like Google or the Internet Archive provide technical support or grants, they have no say in product decisions. The product roadmap is published and open to public critique. Any attempt to influence it would be rejected by the community.

Why don’t they just copy features from other encyclopedias or apps?

Other platforms prioritize engagement and retention. Wikipedia prioritizes accuracy and neutrality. Copying a “trending now” feed or a comment section would violate core policies. Even small features like upvotes or badges have been tested and rejected because they introduce bias and social pressure. What works for YouTube or Reddit doesn’t work for an encyclopedia.

How do you know if a feature is working after it’s released?

Metrics are tracked publicly: edit success rates, time per edit, error rates, and retention of new editors. But the real test is community feedback. If editors stop using it, complain about it, or revert it, the team investigates. Features that don’t improve the editing experience are quietly retired. There’s no vanity metric like “daily active users.” Only impact on content quality matters.