When a major earthquake hits Nepal or a wildfire rages through Canada, the first thing millions of people do isn’t call a news channel-it’s open Wikipedia. Within minutes, a page is created. Within hours, it’s updated with death tolls, evacuation routes, and rescue efforts. This isn’t magic. It’s the result of a global, volunteer-driven system built to respond to chaos with clarity.

How a disaster page starts

Disaster coverage on Wikipedia doesn’t begin with editors in a newsroom. It starts with someone, somewhere, typing. Maybe it’s a student in Tokyo watching live footage of a flood in Bangladesh. Maybe it’s a firefighter in California who just saw the first official report on Twitter. They open Wikipedia, search for the event, and find nothing. So they click "Create page."

That first edit is often raw: "Fire in Los Angeles, 100 homes destroyed, evacuations ongoing." No sources. No structure. Just facts as they’re known. But that’s enough. The system is designed to work with fragments. Within 15 minutes, another editor finds the official fire department’s Twitter account and adds a link. A third checks the USGS earthquake database and inserts coordinates. A fourth fixes the grammar. No one is in charge. But everything gets better, fast.

This isn’t just fast. It’s faster than most news outlets. In 2023, when a train derailment occurred in East Palestine, Ohio, Wikipedia had a live-updating page with maps, chemical names, and air quality reports within 47 minutes. The Associated Press didn’t publish its first detailed article until 82 minutes later.

The rules that keep it accurate

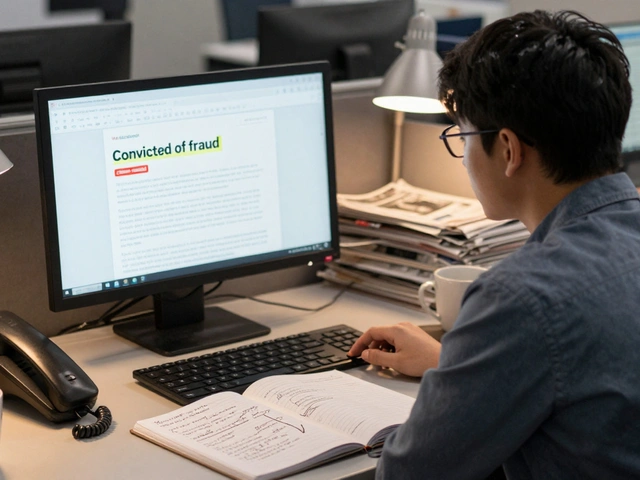

Wikipedia doesn’t allow speculation. No "reports suggest," no "many believe." Every claim needs a reliable source. That’s the rule. And it’s enforced by thousands of volunteers who monitor edits in real time.

During the 2022 earthquake in Turkey, false claims about building collapses in Istanbul spread across social media. Within two hours, Wikipedia editors flagged and removed 17 unsupported death tolls. They replaced them with numbers from Turkey’s AFAD agency-only after confirming the agency’s official website had updated its page. Editors use archived snapshots from government sites, press releases from verified agencies, and trusted news organizations like Reuters or BBC. Personal blogs, Reddit threads, and unverified social media accounts? Blocked.

There’s also a system called "semi-protection." When a page gets heavy traffic during a crisis, only registered users with a few days of editing history can make changes. This stops bots, trolls, and hoaxers from flooding the page with lies. During the 2023 Hamas-Israel conflict, over 200 disaster-related pages were semi-protected within 12 hours.

Who edits these pages?

It’s not journalists. It’s not experts. It’s ordinary people-teachers, engineers, retirees, high school students-who care enough to check facts. Some have no formal training in journalism. Others are retired reporters. A few are even emergency responders.

There’s a group called "WikiProject Disaster Response" with over 1,200 active members. They track breaking events, assign page monitors, and coordinate edits across languages. During the 2024 earthquake in Syria, they worked across Arabic, English, Turkish, and French versions to ensure consistency. One volunteer, a nurse in Aleppo, updated medical supply needs based on firsthand reports from local clinics. Another, a student in Toronto, cross-checked satellite imagery from NASA to confirm damage zones.

They don’t get paid. They don’t get credit. But they get results. In 2023, Wikipedia’s disaster pages received over 1.2 billion views. Many of those visits came from people in affected regions with no internet access outside of Wikipedia-because it loads fast, works on low bandwidth, and doesn’t need an app.

From live updates to long-term records

Disaster coverage doesn’t end when the headlines fade. Wikipedia becomes the permanent archive.

After the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, the page was updated daily for over two years. It documented radiation levels, cleanup progress, government responses, and health studies. Today, it’s the most cited source for researchers studying nuclear accident responses. Universities in Japan and Germany use it as a primary reference in environmental science courses.

Compare that to news websites, which often delete or archive old articles behind paywalls. Wikipedia keeps everything. Every edit is saved. Every source is linked. Every revision can be traced back to the minute it was made. That’s why the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami page still exists-complete with early death estimates that were later corrected, showing how understanding evolved over time.

Post-event analysis on Wikipedia isn’t just summaries. It’s documentation of uncertainty. It shows how information changed. It reveals what was known, what was guessed, and what was wrong. That’s not a flaw. It’s the point.

Why it works when others fail

Traditional media struggles during disasters. Deadlines. Editorial bias. Limited staff. Corporate ownership. Wikipedia has none of those.

It doesn’t need ratings. It doesn’t sell ads. It doesn’t prioritize drama over data. When a fire spreads, Wikipedia doesn’t show burning buildings for clicks. It shows evacuation maps. When a disease outbreak hits, it doesn’t speculate about origins. It links to WHO bulletins and peer-reviewed studies.

Its strength isn’t speed alone. It’s reliability over time. It’s transparency. You can see every change. You can check every source. You can compare versions from hours apart and watch the truth emerge.

In 2025, researchers from Stanford analyzed 3,400 disaster pages and found that 92% of the final content was accurate, compared to 68% for major news outlets’ first reports. The difference? Wikipedia’s delay wasn’t a weakness-it was a filter. It took time for sources to be verified. And that’s exactly what made it more trustworthy.

What’s next for disaster coverage

Wikipedia is testing new tools. AI bots now flag edits that contradict trusted sources. One tool checks if a death toll matches official government updates. Another scans news articles for duplicate claims and warns editors about potential misinformation.

There’s also a push to integrate with emergency services. In Japan, local governments now share real-time alerts directly with Wikipedia editors through secure channels. In the Philippines, civil defense agencies train volunteers to update Wikipedia during typhoons.

The goal isn’t to replace journalists. It’s to complement them. Newsrooms report the story. Wikipedia records the facts. Together, they create a fuller picture.

When the next disaster hits, someone will open Wikipedia. They won’t find a headline. They’ll find a living document-constantly updated, endlessly checked, and always open. That’s not just information. That’s accountability in action.

Can anyone edit a Wikipedia disaster page during a crisis?

During major events, pages are often semi-protected, meaning only registered users with a few days of editing history can make changes. This stops anonymous trolls and bots from spreading false information. But anyone can still view the page, suggest edits on the talk page, or report problems.

How does Wikipedia avoid false information during fast-moving events?

Wikipedia requires all claims to be backed by reliable sources-like government agencies, major news outlets, or peer-reviewed studies. Editors actively remove unverified claims, even if they seem plausible. During the 2023 Turkey earthquake, over 50 false death tolls were removed within hours because they came from unconfirmed social media posts.

Is Wikipedia used by emergency responders?

Yes. In Japan, Taiwan, and parts of Europe, emergency management teams regularly check Wikipedia for real-time updates during disasters. Some agencies even train volunteers to update Wikipedia pages with official data, knowing it’s one of the most accessed sources by the public.

Why do researchers cite Wikipedia for disaster data?

Because it’s transparent. Researchers can trace every fact back to its source and see how information changed over time. Unlike news sites that delete old articles, Wikipedia keeps every version. This makes it invaluable for studying how misinformation spreads-and how truth emerges.

Does Wikipedia cover smaller disasters too?

Yes. Even local events like a bridge collapse in rural Iowa or a chemical spill in a small town get pages if there’s enough public interest or official reporting. These pages often become the only permanent record of the event, especially when local media can’t afford to follow up.