Wikipedia doesn’t decide what’s true. It reports what reliable sources say. That’s the core rule behind how it handles everything from climate change to homeopathy. When a topic sits at the edge of science-like astrology, energy healing, or anti-vaccine claims-Wikipedia’s job isn’t to judge it. It’s to show how the world sees it.

What counts as a reliable source?

Wikipedia doesn’t trust blogs, YouTube videos, or personal websites. It relies on peer-reviewed journals, university textbooks, major newspapers, and established science magazines. If a claim about a miracle cure appears only on a wellness blog, it won’t make it into Wikipedia. But if five medical journals published studies debunking it, that’s the version you’ll see.

For example, the Wikipedia page on homeopathy doesn’t say, "This is fake." Instead, it states: "Homeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine based on the idea that substances that cause symptoms in healthy people can cure similar symptoms in sick people." It then lists multiple systematic reviews from the Cochrane Collaboration and the UK House of Commons Science and Technology Committee concluding there’s no evidence homeopathy works beyond placebo.

This isn’t censorship. It’s sourcing. Wikipedia’s editors follow a simple principle: if no credible source says it, it doesn’t belong.

How pseudoscience gets labeled

Wikipedia doesn’t slap labels on ideas. It lets the scientific community do that. Terms like "pseudoscience," "quackery," or "fringe theory" appear only when major academic institutions, government bodies, or professional organizations have used them repeatedly.

The term "pseudoscience" appears on Wikipedia because it’s used by the National Academy of Sciences, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and hundreds of peer-reviewed papers. If a term isn’t used in reliable sources, Wikipedia won’t use it either-even if it feels obvious.

Take the case of flat Earth theory. Wikipedia doesn’t call it "crazy." It says: "Flat Earth beliefs contradict established scientific evidence and are rejected by the scientific community." Then it cites NASA, the Royal Astronomical Society, and textbooks used in high school physics classes. The tone isn’t angry. It’s factual. The evidence speaks for itself.

Balance isn’t fairness

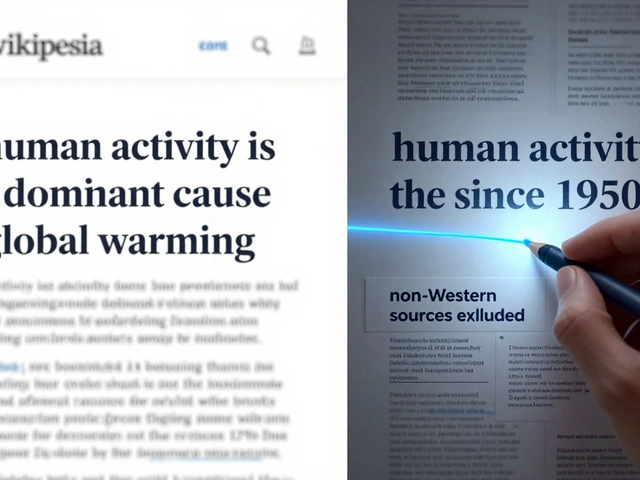

One of the biggest misunderstandings about Wikipedia is that it tries to give "equal time" to all sides. That’s not true. It gives weight to what sources say.

If 97% of climate scientists agree humans are causing global warming, Wikipedia’s climate change page reflects that. It doesn’t say, "Some say it’s real, others say it’s not." It says: "The overwhelming majority of climate scientists agree that human activity is the dominant cause of global warming since the mid-20th century." Then it lists the IPCC reports, the American Meteorological Society, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration as sources.

On the flip side, a Wikipedia page about anti-vaccine claims doesn’t give equal space to vaccine denial. It acknowledges that some people believe vaccines cause autism-but then immediately cites the 1998 Lancet paper that started the myth, explains how it was retracted, and lists 25 large-scale studies from the CDC, WHO, and the Cochrane Library that found no link. The claim gets mentioned, but only as a debunked idea, not a legitimate debate.

This is called "proportional representation." Wikipedia doesn’t pretend all opinions are equally valid. It shows what science says, and how much support it has.

What happens when fringe ideas gain traction?

When a pseudoscientific idea spreads online-like the belief that 5G causes COVID-19-Wikipedia doesn’t ignore it. It documents it, but with clear context.

The 2020 Wikipedia page on "5G and health" includes a section titled "Conspiracy theories and misinformation." It lists specific claims, then cites the World Health Organization, the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection, and peer-reviewed studies showing no biological mechanism for harm at 5G exposure levels. It doesn’t say "this is nonsense." It says: "These claims have been widely debunked by scientific bodies."

This approach keeps the page useful for people searching for answers, while making it clear which ideas are supported by evidence and which aren’t.

Why this matters

Wikipedia is the fifth most visited website in the world. Millions of people use it as their first stop for understanding science. If it gave equal weight to every claim, it would mislead people into thinking there’s a real scientific controversy where there isn’t one.

Imagine a student looking up "vaccines and autism." If Wikipedia presented both sides as equally valid, they might walk away thinking the science is divided. But because Wikipedia shows the overwhelming consensus-and the origin of the myth-it helps them understand the truth.

Wikipedia’s method isn’t perfect. Editors sometimes miss updates. Biased users occasionally try to push agendas. But the system has checks: edit histories, discussion pages, and a community of thousands of volunteers who monitor changes. If someone tries to insert false claims, they’re usually reversed within hours.

What Wikipedia won’t do

Wikipedia won’t:

- Declare a theory "true" or "false" on its own authority

- Use emotional language like "dangerous," "ludicrous," or "disgusting"

- Give space to claims that no reliable source supports

- Let fringe views dominate the narrative just because they’re loud online

It also won’t hide controversial topics. The page on eugenics doesn’t sugarcoat history. It explains how the movement was once supported by universities, governments, and Nobel laureates-and how it led to forced sterilizations and genocide. It doesn’t avoid the dark parts. It documents them with sources.

The real challenge: gray areas

Not everything is black and white. Some topics sit in the middle-like acupuncture or mindfulness meditation. These aren’t clearly pseudoscientific, but they’re not always fully accepted by mainstream medicine either.

Wikipedia handles these by being precise. The acupuncture page says: "Some studies suggest acupuncture may help with chronic pain, but the evidence is mixed and the mechanisms are not well understood." It cites randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, and reviews from the Journal of the American Medical Association and the National Institutes of Health. It doesn’t say "it works." It doesn’t say "it’s fake." It says what the evidence shows-and how strong it is.

This is the gold standard: transparency about uncertainty. If science doesn’t know yet, Wikipedia says so.

How you can trust it

Wikipedia’s strength isn’t that it’s always right. It’s that you can check every claim. Every sentence with a citation has a source you can look up. Click the number at the end of a sentence, and you’ll see the journal, book, or report it came from.

That’s more than you can say for most websites. Most blogs, news sites, and even some medical portals don’t link to their sources. Wikipedia does. That’s why researchers, students, and fact-checkers often use it as a starting point-even if they don’t cite it directly.

Wikipedia doesn’t pretend to be the final word. It’s a mirror. It reflects what the world of science, medicine, and scholarship says. And when that mirror is clear, it helps people see the difference between what’s real and what’s just noise.

Does Wikipedia ban pseudoscience entirely?

No. Wikipedia doesn’t ban ideas. It documents them, but only if reliable sources mention them. Pseudoscientific topics like homeopathy, astrology, or flat Earth are included because they’re widely discussed-but they’re presented with context, citations, and clear references to scientific consensus. The goal isn’t to erase them, but to show how the scientific community views them.

Why doesn’t Wikipedia just say pseudoscience is wrong?

Wikipedia avoids making judgments on its own. Instead, it reports what experts and authoritative institutions say. If the American Medical Association, the National Science Foundation, or peer-reviewed journals call something pseudoscience, Wikipedia uses that language. It lets the sources do the evaluating, not the editors.

Can anyone edit Wikipedia to push pseudoscience?

Yes, anyone can try. But edits are reviewed by thousands of volunteers. If someone adds false or unsupported claims, they’re usually reverted quickly. High-traffic pages like those on vaccines, climate change, or evolution have additional protections, including semi-protection and oversight by experienced editors. The edit history is public, so any attempt to manipulate content is visible and trackable.

Is Wikipedia biased against alternative medicine?

Wikipedia doesn’t favor mainstream medicine over alternative medicine-it favors reliable evidence. If a treatment has been tested in multiple rigorous studies and shown to be effective, it’s included. If it hasn’t, it’s noted as lacking evidence. For example, the page on chiropractic acknowledges some limited benefits for back pain but also notes that many claims made by practitioners aren’t supported by science. The standard is evidence, not ideology.

How does Wikipedia handle new scientific discoveries?

New findings are added only after they’ve been published in peer-reviewed journals and confirmed by other researchers. A single study isn’t enough. Wikipedia waits for consensus to form. For example, when the first studies on CRISPR gene editing came out, they weren’t immediately added as breakthroughs. Only after multiple labs replicated the results and major journals reviewed them did Wikipedia update its page to reflect their significance.

What to do if you find a misleading Wikipedia page

If you think a page is wrong or biased, don’t just complain. Check the talk page. See what other editors are saying. Look at the citations. If you find a better source, you can edit it yourself-or start a discussion. Wikipedia thrives on collaboration, not confrontation.

The system isn’t perfect. But it’s designed to get better over time-with more eyes, more sources, and more accountability than any single expert or organization could provide.