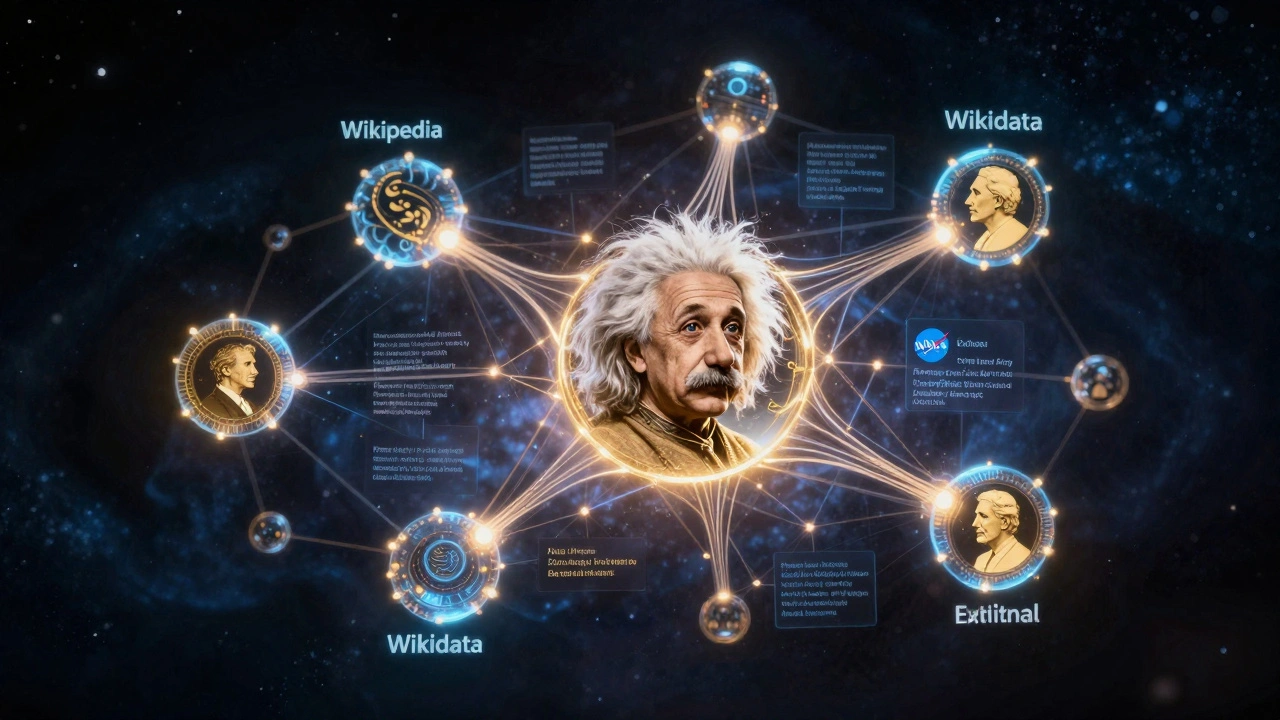

Imagine you search for Albert Einstein on Wikipedia. You see his birth date, Nobel Prize, theory of relativity - all neatly laid out. But behind that page, something far more powerful is happening. A machine-readable web of facts is connecting Einstein to thousands of other people, places, and ideas - not just in Wikipedia, but across the entire internet. That’s the power of interoperable knowledge graphs.

What Is a Knowledge Graph?

A knowledge graph isn’t a chart you print out. It’s a digital network of real-world things - people, places, concepts - linked by relationships. Think of it like a giant spiderweb where each dot is an entity and each line is a fact. For example: Albert Einstein worked at Princeton University, and Princeton University is located in New Jersey.

Unlike old databases that store data in rigid tables, knowledge graphs understand context. They know that "Apple" could mean a fruit, a company, or a record label - and they pick the right one based on what’s around it. This makes them perfect for search engines, AI assistants, and smart applications that need to reason, not just retrieve.

Wikipedia: The Human-Curated Foundation

Wikipedia is the largest human-edited encyclopedia on Earth. Over 60 million articles in 300+ languages. But here’s the catch: Wikipedia was built for people, not machines. Articles are written in plain text. Tables are messy. Links are for clicking, not parsing.

That changed in 2012 when Wikimedia launched Wikidata. Wikidata took all the structured data from Wikipedia - birth dates, locations, awards - and turned them into clean, reusable facts. Now, when you edit a Wikipedia infobox, you’re often editing Wikidata behind the scenes. A single change in Wikidata can update hundreds of Wikipedia pages at once.

Wikipedia gives us the narrative. Wikidata gives us the structure. Together, they form the backbone of the most widely used knowledge graph in the world.

Wikidata: The Machine-Readable Core

Wikidata isn’t a website you read. It’s a database you query. Every item has a unique ID - like Q937 for Albert Einstein. Every fact is a triple: subject, predicate, object. For example:

- Q937 - P106 - Q36180 (Einstein - occupation - theoretical physicist)

- Q937 - P569 - 1879-03-14 (Einstein - date of birth - March 14, 1879)

These triples are language-independent. So whether you speak Spanish, Japanese, or Swahili, you’re looking at the same underlying facts. That’s why Google, Bing, and Apple use Wikidata to power their knowledge panels. When you ask Siri, "When did Einstein die?" - she’s not reading Wikipedia. She’s pulling from Wikidata.

Wikidata also lets anyone contribute. You don’t need to write an article. You just add a fact: "This painting was created in 1923," or "This actor starred in this movie." Over 100 million items are now in Wikidata, and more than half were added by volunteers outside the Wikimedia community.

External APIs: Connecting the World’s Data

Wikidata is powerful, but it doesn’t have everything. What about stock prices? Real-time weather? Live sports scores? That’s where external APIs come in.

Organizations like the Library of Congress, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the European Space Agency expose their data through public APIs. These APIs return structured data in formats like JSON or RDF. When you connect them to Wikidata, you’re not just adding facts - you’re making them live.

For example:

- A bot pulls daily population data from the UN’s API and updates the population of countries in Wikidata.

- A museum uses its own collection API to link paintings to their artists in Wikidata, so anyone searching for "Van Gogh" can see every painting he made, not just the famous ones.

- Medical researchers connect clinical trial data from NIH to disease entries in Wikidata, helping AI models predict treatment outcomes.

This isn’t science fiction. It’s happening right now. Tools like OpenRefine and Wikidata Integrator let researchers and developers automatically sync external data with Wikidata. No coding required for basic tasks.

How They Work Together: A Real Example

Let’s say you’re building an app that shows where Nobel laureates lived and worked.

First, you query Wikidata for all people who won a Nobel Prize in Physics. Wikidata returns a list of 227 people, each with their birthplace, death place, and institutions.

Then, you connect to the Google Maps API to get coordinates for each location. You pull in the GeoNames API to verify city names and administrative regions.

Finally, you use the Wikipedia API to fetch short biographies for each laureate and display them in your app.

None of this works if any of these systems were isolated. Wikidata gives you the list. Google Maps gives you the map. Wikipedia gives you the story. Together, they create something richer than any single source.

This is interoperability in action: systems speaking the same language so they can work as one.

Why Interoperability Matters Now

In 2025, AI models are trained on massive datasets - but they still hallucinate. They make up facts because they don’t know what’s true. Knowledge graphs fix that.

When you train an AI on a verified knowledge graph, you’re feeding it trusted facts, not random web text. Companies like Meta, Microsoft, and IBM now build their AI assistants on top of Wikidata and linked open data. Why? Because accuracy beats speed.

Interoperability also helps libraries, museums, and schools. A high school teacher in Nairobi can pull data from Wikidata to show students how global science collaborations evolved. A historian in Berlin can trace migration patterns by linking archival records to modern geographic data.

The future of knowledge isn’t a single database. It’s a network - open, connected, and constantly updated.

Challenges and Limitations

It’s not perfect. Some external APIs are slow, expensive, or require login keys. Others change their format without warning. Wikidata relies on volunteers - so some entries are incomplete or outdated.

Also, not all data is equal. A fact from a peer-reviewed journal is more reliable than one from a blog. Knowledge graphs need ways to tag source quality. Projects like PROV-O (Provenance Ontology) are trying to solve this by tracking where each fact came from.

And then there’s bias. Most knowledge graphs reflect the cultures and languages that contribute the most. English dominates. African, Indigenous, and Asian perspectives are underrepresented. Efforts like WikiProject Africa and the Decolonial Wikidata Initiative are working to fix that - but it’s a long road.

The Road Ahead

By 2030, experts predict that over 80% of structured data on the web will be connected through knowledge graphs. The goal isn’t just to answer questions - it’s to understand them.

Imagine asking your phone: "Show me all climate scientists who worked in the Arctic before 1980 and published papers in non-English journals." Today, that’s impossible. Tomorrow, with better interoperability, it won’t be.

The tools are getting better. New standards like JSON-LD and RDF-star make it easier to link data across systems. AI is getting smarter at spotting contradictions and filling gaps. And more governments are opening their data - like the U.S. government’s data.gov and the EU’s Europa Data Portal.

The future of knowledge isn’t stored in one place. It’s woven together - from Wikipedia’s human stories, to Wikidata’s machine logic, to the live feeds from labs, libraries, and governments around the world.

Can I use Wikidata in my own app?

Yes. Wikidata offers a free public API. You can query it using SPARQL, a language for asking questions about data. Many developers use it to power apps, research tools, and educational platforms. You don’t need permission - just follow their usage guidelines.

Is Wikidata better than Google’s Knowledge Graph?

They serve different purposes. Google’s Knowledge Graph is optimized for search results and speed. Wikidata is open, editable, and designed for long-term accuracy and reuse. Many companies, including Google, actually use Wikidata as a source for their own knowledge graphs. Wikidata is the public foundation; Google’s is a private layer on top.

How do I add data to Wikidata?

You can edit Wikidata directly at wikidata.org. You need a free account. Then you can add new items (like a person or a book) or update existing ones with facts. There are tutorials and templates to help beginners. Many libraries and universities now train students to contribute as part of digital literacy courses.

Do I need to know coding to work with knowledge graphs?

No. Tools like OpenRefine, QuickStatements, and the Wikidata Toolkit let you import, clean, and upload data without writing code. But if you want to build apps that use knowledge graphs, learning basic SPARQL or Python will help. Many universities now offer free online courses on linked data.

Why doesn’t everyone use knowledge graphs yet?

Many organizations still rely on old databases that are hard to change. There’s also a lack of awareness. Some think knowledge graphs are only for tech giants. But small nonprofits, schools, and local archives are using them now to make their collections searchable and connected. The barrier is falling - faster than most realize.