Ever notice how a date on Wikipedia shows up as 25 December 2025 in one language but 12/25/2025 in another? Or how a person’s name changes spelling depending on whether you’re reading in Japanese, Arabic, or Spanish? That’s not a mistake. It’s localization-and it’s one of the most complex, quietly brilliant systems running behind the scenes on Wikipedia.

Why Wikipedia Doesn’t Use One Global Format

Wikipedia isn’t a single website. It’s over 300 separate language editions, each run by volunteers who speak that language and live in that culture. A Polish editor doesn’t want to see months written as numbers. A Chinese reader expects year-first dates. A Brazilian user won’t recognize British spelling. If Wikipedia forced everyone to use American date formats or English names, it would alienate half its audience.That’s why localization isn’t optional-it’s core to Wikipedia’s mission of free knowledge for everyone. The platform doesn’t just translate words. It adapts the entire cultural context around them.

Date Formats: More Than Just Numbers

Dates on Wikipedia follow local conventions exactly. There’s no universal standard. Here’s how it breaks down:- In the United States: Month/Day/Year → 12/25/2025

- In most of Europe and Australia: Day/Month/Year → 25/12/2025

- In Japan and China: Year-Month-Day → 2025-12-25

- In Sweden and some other countries: Year-Month-Day with leading zeros → 2025-12-25

- In Arabic-speaking regions: Often written in Arabic numerals, right-to-left → ٢٥/١٢/٢٠٢٥

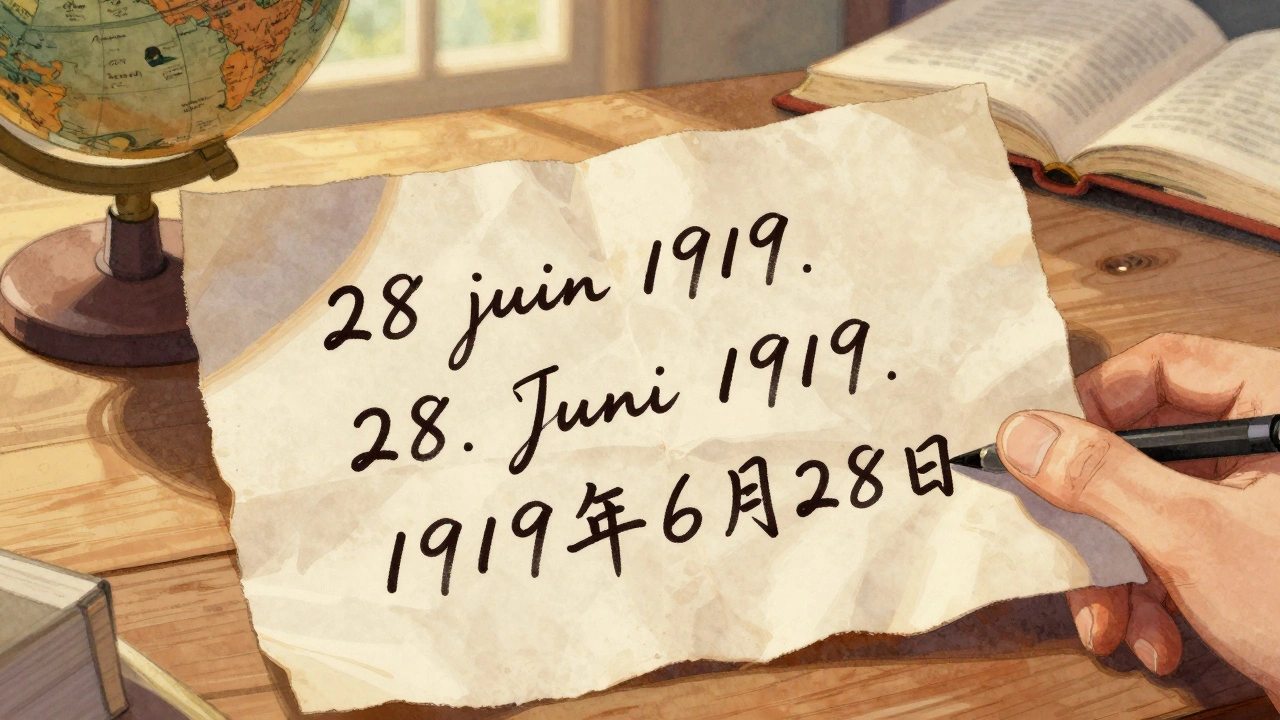

Wikipedia’s software automatically detects the language version you’re using and displays dates accordingly. But it goes further. If you’re reading about a historical event like the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, you’ll see the date in the format used by the country where it happened-even if that’s different from your own. The article on the treaty in French shows 28 juin 1919. In German, it’s 28. Juni 1919. In Chinese, it’s 1919年6月28日.

This isn’t just about looks. It’s about clarity. A date like 05/06/2025 could mean June 5th or May 6th. By sticking to local formats, Wikipedia avoids confusion for its readers.

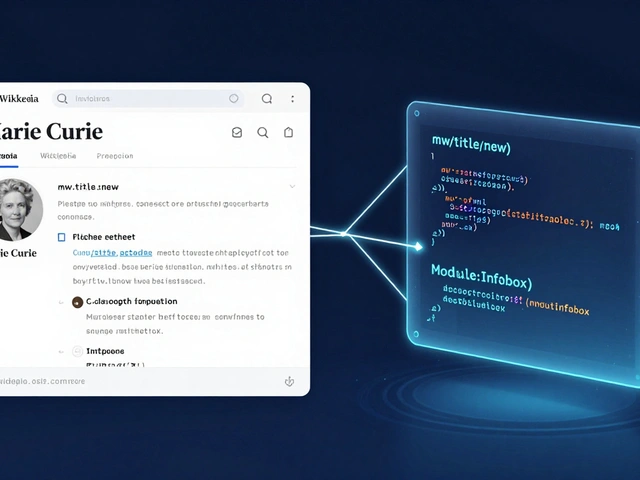

Names: Spelling, Order, and Cultural Respect

Names are even trickier than dates. In English, we put the given name first: Marie Curie. In many East Asian languages, the family name comes first: 居里夫人 (Jūlǐ Fūrén) in Chinese, キュリー夫人 in Japanese. Wikipedia doesn’t force English order onto other languages.For people with non-Latin names, Wikipedia uses the most widely accepted local spelling. For example:

- Osama bin Laden in English

- أُسَامَة بِن لَادِن in Arabic

- 오사마 빈 라덴 in Korean

- أُسَامَة بِن لَادِن in Arabic

- Осама бин Ладен in Russian

Wikipedia doesn’t transliterate names into English unless it’s the standard in English-language media. So you won’t see “Mao Tse-tung” on the Chinese Wikipedia-it’s 毛泽东. On the English Wikipedia, you’ll see both versions, with the original script in parentheses for clarity.

Titles and honorifics also change. In Japanese, you’ll see 田中さん (Tanaka-san). In French, it’s M. Dupont. In Arabic, it’s الدكتور أحمد (Dr. Ahmed). Wikipedia respects these conventions because they carry cultural meaning.

Cultural Conventions: What’s Common Elsewhere Isn’t Common Here

It’s not just dates and names. Entire cultural norms shape how information is presented.For example:

- In Germany, Wikipedia articles on government officials list their party affiliation prominently. In the U.S., that’s less common unless it’s politically relevant.

- In India, Wikipedia articles often include local language names for places. The city of Mumbai is listed as मुंबई in Hindi and மும்பை in Tamil.

- In Russia, dates of birth and death are often written in the Old Style (Julian) calendar for historical figures, with the New Style (Gregorian) in parentheses.

- In Arabic Wikipedia, text flows right-to-left. Tables, images, and even footnotes adjust their layout automatically.

Even something as simple as metric vs. imperial units follows local norms. The English Wikipedia uses both, but the French version defaults to metric. The Arabic version uses metric unless discussing U.S.-related topics. Temperature is shown in Celsius unless the subject is American.

Wikipedia editors follow community guidelines called Manual of Style pages for each language. These are not top-down rules-they’re built by consensus. If a group of editors in Brazil decides that dates should always be written with the month in full (e.g., 25 de dezembro de 2025), that becomes the standard for Portuguese Wikipedia.

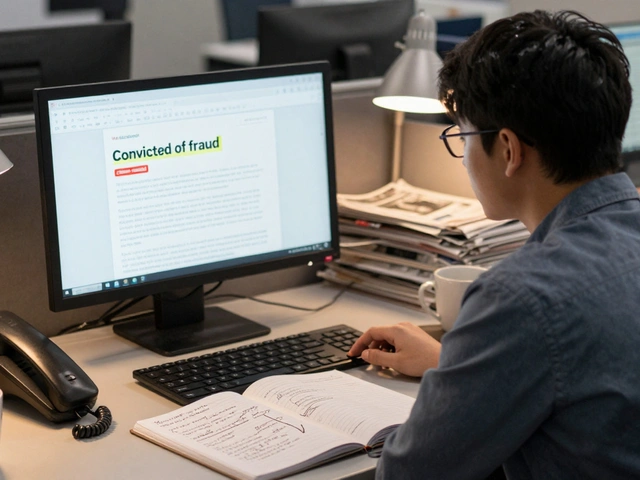

How the System Works Behind the Scenes

Wikipedia doesn’t manually rewrite every date and name in every language. It uses templates and modules that auto-detect language and apply formatting rules.For example, the template {{date}} in English Wikipedia might output December 25, 2025. The same template in Japanese Wikipedia outputs 2025年12月25日. Behind the scenes, the template pulls from language-specific formatting rules stored in the MediaWiki software.

These rules are maintained by volunteer developers and editors who know both the language and the software. If a new country joins the Unicode standard with a new calendar system, someone has to code it into Wikipedia’s system. That’s happened for the Ethiopian calendar, the Islamic Hijri calendar, and even the Hebrew calendar.

For names, Wikipedia uses authoritative sources like national libraries and official government spellings. If there’s a dispute-like whether to write Xi Jinping or Hsi Ching-pin-editors consult academic sources and media usage in the target language.

What Happens When Cultures Clash?

Localization isn’t always smooth. Sometimes, cultural norms conflict.For example, in the English Wikipedia, the article on the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami lists the death toll as “230,000+.” In the Indonesian Wikipedia, it’s written as “227,898” because local authorities published that exact number. Editors in both communities debated for months over whether to use rounded figures or precise ones. The compromise? The English version kept the rounded number for readability, while the Indonesian version kept the precise figure-and both are cited with sources.

Another example: gender-neutral language. In Spanish, some editors push for gender-inclusive terms like estudiantes instead of estudiantes y estudiantes. In Arabic, gender is grammatically required, so neutrality is harder to express. Wikipedia doesn’t force one approach-it lets each language community decide.

These debates happen in talk pages, in edit summaries, and in community polls. The goal isn’t uniformity-it’s respect.

Why This Matters Beyond Wikipedia

Wikipedia’s approach to localization is a model for how global platforms should handle cultural diversity. It doesn’t assume one culture is the default. It doesn’t erase local identities to make things easier. It lets each community speak in its own voice.That’s why Wikipedia is still one of the most trusted sources worldwide-even in countries where other platforms are blocked or censored. People trust it because it feels familiar. The dates look right. The names are spelled how they’ve always been spelled. The units match what they use every day.

For anyone building a global product-whether it’s an app, a website, or a database-Wikipedia offers a simple lesson: localization isn’t just translation. It’s adaptation. It’s honoring how people live, think, and remember.

What You Can Do as a Reader

If you’re reading Wikipedia in your native language, you’re already part of this system. But if you’re curious, try switching to another language version. Look up your hometown, a famous person, or a holiday. See how the date is written. See how the name is spelled. Notice what details are included-or left out.You’ll start seeing patterns. You’ll notice that some cultures emphasize family lineage. Others focus on dates. Some list causes of death; others don’t. These aren’t errors. They’re cultural fingerprints.

Wikipedia doesn’t pretend to be one thing for everyone. It’s a thousand things-and that’s what makes it powerful.