Wikipedia is one of the most used sources of information in academic research. But here’s the problem: if you cite a Wikipedia edit or use its data in a study, can someone else repeat your work? Most of the time, the answer is no. Researchers pull data from Wikipedia, run analyses, and publish results-without sharing the exact code, timestamps, or data dumps they used. That makes their findings impossible to verify. Reproducibility isn’t just a buzzword in science; it’s the foundation of trust in research. And when it comes to Wikipedia, the lack of it is widespread.

Why Wikipedia Research Often Can’t Be Reproduced

Wikipedia changes every second. An article you analyzed on January 5, 2025, might look completely different on January 20, 2025. If you didn’t save the exact version you worked with, your results are tied to a moving target. Many studies don’t record which revision ID they used, which means others can’t pull the same data.

Even worse, researchers often use custom scripts to extract data from Wikipedia’s API or HTML dumps. But these scripts rarely get published. One 2023 analysis of 120 peer-reviewed papers using Wikipedia data found that only 18% included any code. Of those, half had broken links or incomplete instructions. Without the code, you can’t replicate the filtering, cleaning, or analysis steps. You’re left guessing what the original researchers did.

And then there’s the data. Researchers download Wikipedia edits, page views, or edit histories-but they don’t share the actual files. They say things like, “We used data from English Wikipedia in 2024.” That’s not enough. Which dump? The monthly one? The daily? Did you filter out bots? Did you exclude stub articles? Without these details, your work is a black box.

What Reproducibility Actually Looks Like in Practice

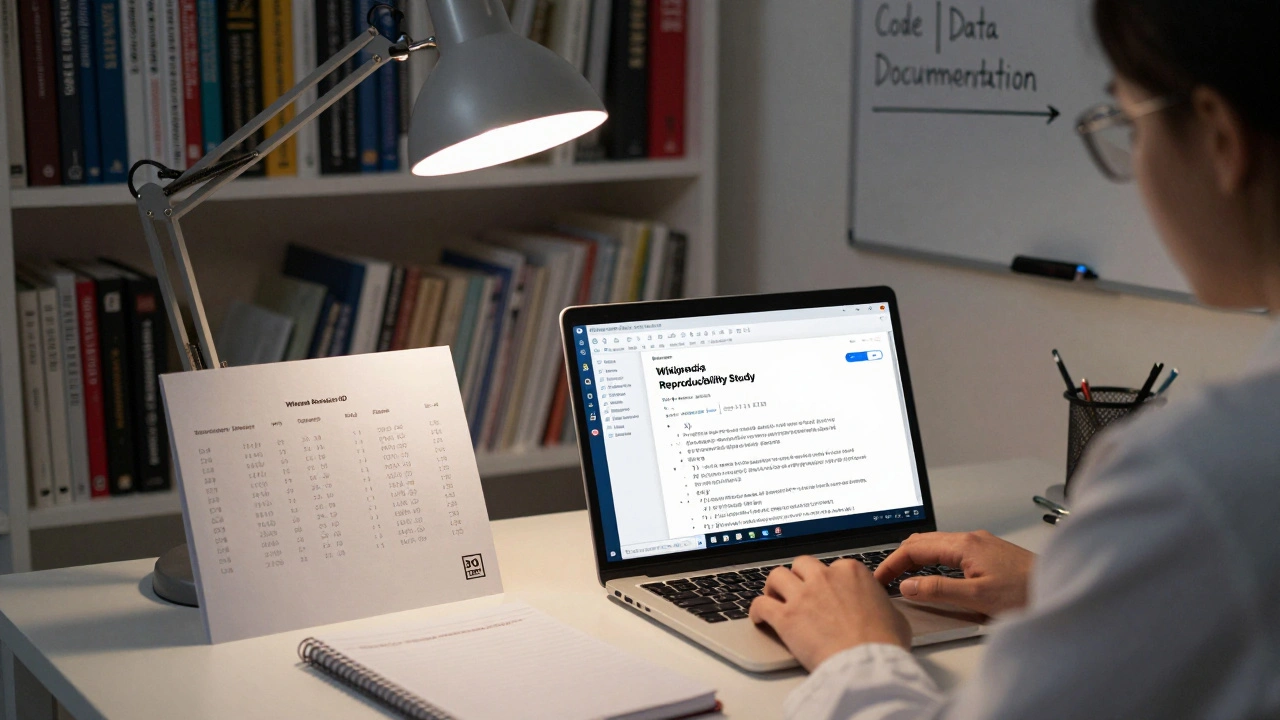

Reproducibility means someone else can take your exact steps and get the same result. That requires three things: code, data, and documentation.

Let’s say you’re studying how political bias changes in Wikipedia articles during election seasons. You write a Python script that:

- Downloads all edits to 500 political articles from March 1 to November 30, 2024

- Filters out edits made by registered bots

- Calculates sentiment scores using a pre-trained model

- Plots trends over time

To make this reproducible, you need to:

- Share the exact script (in a public repo like GitHub)

- Upload the data dump you used (e.g., the Wikipedia revision dump from June 15, 2024)

- Write a README explaining how to run the script, what dependencies are needed, and what each step does

That’s it. No fancy tools. No paywalls. Just clear, shareable files.

Some researchers are already doing this. In 2024, a team at the University of Edinburgh published a study on gender bias in Wikipedia biographies. They shared their code on GitHub, the exact Wikipedia dump they used (with SHA-256 hash for verification), and even a Jupyter notebook showing every step of their analysis. Other researchers replicated their findings in under two hours. That’s reproducibility in action.

How to Share Your Code Properly

Sharing code sounds simple, but most people do it wrong. Here’s how to get it right:

- Use GitHub, GitLab, or Bitbucket. Don’t send zip files via email.

- Include a

requirements.txtorenvironment.ymlfile listing all Python packages and versions. - Document every function. Even if it’s just a one-line comment: “This removes edits by users with fewer than 10 edits.”

- Use version control. Commit changes with clear messages: “Fixed date parsing bug for 2024 dumps.”

- License your code. Use MIT or CC0 so others can use it without legal worry.

Don’t wait until your paper is accepted to share code. Do it when you start. That way, you’re not scrambling at the last minute. And if your code breaks later? That’s okay. Archive it with a timestamped DOI using Zenodo. That way, your exact version stays frozen in time.

How to Share Your Data Correctly

Wikipedia data comes in many forms: edit histories, page views, category memberships, talk page discussions. You need to be specific.

Here’s what to include:

- The exact Wikipedia dump ID (e.g.,

enwiki-20240601-pages-articles-multistream.xml.bz2) - How you filtered the data (e.g., “Only included articles with over 100 edits and non-bot users”)

- The time range (start and end dates, in UTC)

- Any preprocessing steps (e.g., “Removed all edits with edit summaries containing ‘bot’”)

- The file format (CSV, JSON, Parquet?) and how to open it

Upload your data to a public repository like Zenodo, Figshare, or OSF. These platforms assign a DOI, which makes your dataset citable. Don’t just link to Wikipedia’s own dumps-those change. Your data is your snapshot. Lock it in place.

One researcher analyzed how misinformation spreads in Wikipedia’s “current events” pages. She uploaded her filtered dataset of 12,000 edits to Zenodo with a DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1234567. Within weeks, three other teams used her data to test different models. None of them had to re-download or re-filter 12,000 edits. That’s efficiency. That’s trust.

Common Mistakes That Break Reproducibility

Even well-meaning researchers mess this up. Here are the top five mistakes:

- Using local file paths like

C:\Users\John\data\wikipedia.csv. That won’t work on another computer. - Hardcoding API keys in scripts. Never commit credentials to public repos.

- Not specifying time zones. Wikipedia uses UTC. If you used local time, your analysis is wrong.

- Assuming everyone knows Wikipedia’s API limits. Your script might fail because it hits rate limits. Document how you handled throttling.

- Not testing the reproducibility yourself. Before submitting your paper, ask a colleague to run your code from scratch. If they can’t get the same numbers, fix it.

One paper claimed to find a 40% increase in female representation in Wikipedia biographies after a 2023 edit-a-thon. But when another team tried to reproduce it, they got 18%. The original author had accidentally filtered out all biographies under 500 words. The mistake wasn’t malicious-it was just unverified.

Why This Matters Beyond Academia

Wikipedia isn’t just a reference. It’s a public record. Millions of people, including journalists, policymakers, and students, rely on it. If research based on Wikipedia is flawed or unreproducible, those decisions are built on sand.

When a news outlet cites a study saying “Wikipedia articles on climate change are 30% more biased than average,” readers deserve to know how that number was calculated. If the code and data aren’t available, the claim is just noise.

Reproducibility turns Wikipedia from a black box into a transparent, verifiable resource. It turns research from opinion into evidence. And it invites more people-students, librarians, citizen scientists-to join the conversation.

Where to Start Today

You don’t need to overhaul your entire workflow. Start small:

- Next time you download Wikipedia data, save the dump ID and timestamp.

- Put your script in a GitHub repo-even if it’s messy.

- Add a README with three bullet points: what you did, how to run it, where the data came from.

- Upload your cleaned dataset to Zenodo.

- Include the DOI and GitHub link in your paper’s methods section.

That’s it. You’ve just made your research more credible, more useful, and more valuable to the world.

Tools and Resources

- WikiPedia API: For pulling live or historical edits

- Wikidata: Structured data linked to Wikipedia articles

- Wikimedia Dumps: Full historical snapshots of Wikipedia content

- GitHub: Host your code publicly

- Zenodo: Get a DOI for your data

- ReproZip: Packages your entire analysis environment

- Open Science Framework (OSF): For managing code, data, and documentation together

These tools are free, open, and designed for exactly this kind of work. Use them.

Why can’t I just link to Wikipedia instead of sharing my data?

Wikipedia changes constantly. A link to an article today might show a different version tomorrow. Your analysis depends on the exact state of the page at the time you studied it. Without saving that snapshot, others can’t verify your results. Linking to Wikipedia is like citing a newspaper article without specifying the date or edition-it’s not enough for research.

Do I need to share my raw Wikipedia data if it’s huge?

No. You don’t need to upload multi-gigabyte dumps. Share only the filtered, cleaned data you actually used in your analysis. For example, if you analyzed 500 articles out of 6 million, upload just those 500 in CSV or JSON format. That’s manageable and meaningful. Keep the raw dumps for your own records, but share the subset that produced your results.

What if my code uses proprietary software or paid APIs?

If your analysis depends on something others can’t access, your work isn’t fully reproducible. Try to replace proprietary tools with open alternatives. For sentiment analysis, use TextBlob or VADER instead of paid services. If you must use a paid tool, document exactly how it was used and provide sample outputs. Transparency still matters-even if full replication isn’t possible.

Can I get in trouble for sharing Wikipedia data?

No. Wikipedia content is licensed under CC BY-SA, which allows sharing and reuse as long as you credit the source. Your scripts and cleaned datasets are your own work and can be licensed as you choose. Just make sure you’re not sharing private user data (like IP addresses or login info), which is protected under Wikimedia’s privacy policy.

How do I cite my own shared code or data?

If you uploaded your data to Zenodo or your code to GitHub, you’ll get a DOI or permanent URL. Cite it like a paper: “Data available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.xxxxxx.” In your paper’s methods section, write: “All code and processed data are publicly available at [URL].” This makes your work citable and traceable.