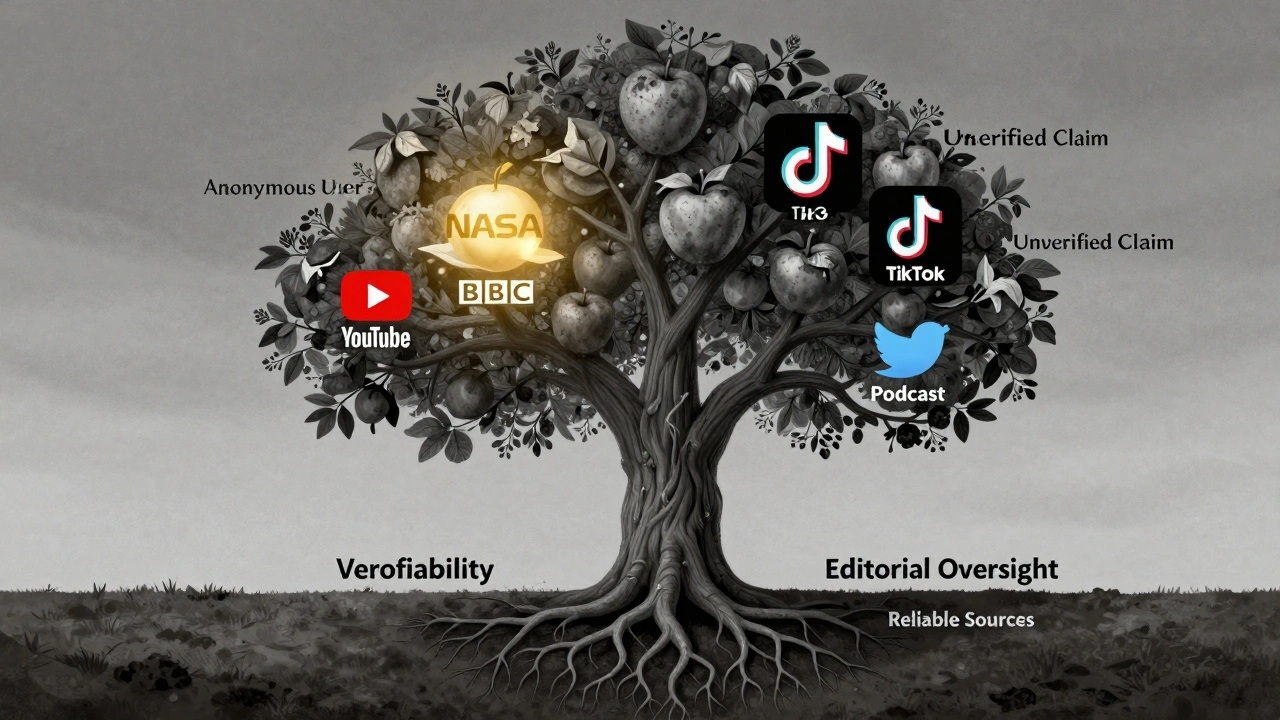

Wikipedia doesn’t ban social media, YouTube, or podcasts outright-but it doesn’t accept them as reliable sources unless they meet strict criteria. If you’ve ever tried to cite a viral TikTok clip or a popular podcast episode in a Wikipedia edit, you’ve probably hit a wall. That’s not because Wikipedia hates new media. It’s because reliability isn’t about popularity. It’s about accountability.

Why Wikipedia cares more about who said it than how many people heard it

Wikipedia’s core rule is verifiability. Every claim needs to be backed by a source that readers can check. A YouTube video with 5 million views doesn’t count if the uploader is an anonymous account with no track record. A podcast guest saying something off-the-cuff doesn’t qualify if the host doesn’t fact-check or provide context. The platform doesn’t care about reach-it cares about trustworthiness.

Think of it this way: if you’re writing about a medical claim, you wouldn’t cite a meme. You’d cite a peer-reviewed journal. The same logic applies to digital media. A tweet from a journalist at The New York Times might pass muster. A tweet from a random user with no credentials won’t.

When YouTube videos can be used as sources

YouTube isn’t automatically unreliable. Many professional news organizations, universities, and government agencies publish official content there. A video uploaded by the BBC, NASA, or the U.S. Census Bureau is treated like any other official publication. These channels have editorial oversight, fact-checking teams, and accountability structures.

For example, if you’re writing about climate data, a video from NASA’s official YouTube channel showing satellite imagery and expert commentary is acceptable. The same video posted by a YouTuber named "EcoTruth2025" with no affiliation, no citations, and no credentials is not.

The key questions to ask:

- Is this channel operated by a known, reputable organization?

- Does the video cite its own sources within the description or visuals?

- Is the content an interview, lecture, or official statement-or just commentary?

If the answer to all three is yes, it’s worth considering. If not, look for a primary source the video references-like a government report, academic paper, or news article-and cite that instead.

Podcasts: the gray zone

Podcasts are trickier. Some are journalistic; others are casual conversations. Wikipedia treats them like any other media: the content matters more than the format.

Podcasts produced by established news outlets-like The Daily from The New York Times, or NPR’s Up First-are acceptable sources. These shows have editors, fact-checkers, and clear journalistic standards. An episode where a reporter interviews a university professor about their published research can be cited, as long as the research itself is referenced.

But a podcast hosted by a self-proclaimed expert who says, "I talked to a guy who works at the FDA and he told me..."? That’s not reliable. Wikipedia requires direct attribution. You can’t cite hearsay, even if it’s delivered in a polished audio format.

Also, avoid citing podcast episodes that are just opinions. Even if the host is well-known, unless they’re presenting verifiable facts with sources, the episode doesn’t meet Wikipedia’s threshold.

Social media: the hardest to use

Social media posts are the most restricted. Twitter (X), Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok are almost never acceptable as standalone sources. Why? Because they’re designed for speed, not accuracy. They lack editorial control. Anyone can post anything. Misinformation spreads faster than corrections.

There are two rare exceptions:

- Official accounts of public institutions: A tweet from @NASA, @WHO, or @WhiteHouse that announces policy, releases data, or confirms an event can be cited. These are treated like press releases.

- Public statements by notable individuals: A tweet from a sitting U.S. senator, a Nobel laureate, or a CEO of a Fortune 500 company that’s directly relevant to their public role may be used-but only if it’s the primary source of the claim and no other reliable source exists.

Even then, you must include the full URL and date. And you must be prepared to defend it in talk page discussions. Many editors will still challenge it unless the post is widely reported by independent media.

For example: if you’re writing about a company’s earnings announcement, cite the official press release on the company’s website. Don’t cite the CEO’s tweet-even if it’s the first place the news broke. The press release is the primary source. The tweet is just a secondary mention.

What Wikipedia considers a reliable source

Wikipedia’s Reliable Sources policy is clear: sources must be published, have editorial oversight, and be independent of the subject. That means:

- Books from academic or commercial publishers

- Peer-reviewed journals

- Major newspapers and magazines (The Guardian, The Atlantic, Der Spiegel)

- Official government or institutional reports

- Reputable news websites (BBC, Reuters, AP, Bloomberg)

- Documentaries from established producers (PBS, BBC, Netflix originals with journalistic teams)

These sources have editors, fact-checkers, legal teams, and reputations to protect. They’re held accountable. Social media and most podcasts lack those safeguards.

How to find better sources when all you have is a viral clip

Let’s say you saw a YouTube video where a scientist explains a new discovery. You want to cite it. But Wikipedia won’t accept the video alone. What do you do?

Follow the trail:

- Check the video description. Does it link to a journal article, press release, or news story?

- Search for the scientist’s name + the topic. Did a major outlet cover it? Did the university issue a press release?

- Look up the study in Google Scholar or PubMed. If it’s real, it’s published somewhere.

- Cite the original source-not the video.

This isn’t extra work. It’s what Wikipedia editors expect. You’re not just adding a link-you’re ensuring the information survives beyond a viral moment.

Why this matters: Wikipedia as a public record

Wikipedia isn’t just a website. It’s one of the most accessed reference tools in the world. Millions of students, journalists, and researchers rely on it. If it starts accepting unverified social media posts as facts, it loses credibility.

Imagine a student writing a paper and citing a TikTok trend as proof of a historical event. That’s not just wrong-it’s dangerous. Wikipedia’s standards exist to prevent that.

Being strict isn’t about being old-fashioned. It’s about protecting the integrity of knowledge. The internet changes fast. Reliable sources don’t.

What happens when you cite unreliable sources

If you add a citation to a Wikipedia article using a YouTube video or podcast without proper context, here’s what usually happens:

- Your edit gets reverted within hours or days

- You get a message from an editor asking for a better source

- Repeated violations can lead to editing restrictions

It’s not personal. It’s policy. Wikipedia editors aren’t trying to shut down new media-they’re trying to keep the encyclopedia trustworthy.

Instead of fighting the system, learn it. Use the Reliable Sources noticeboard to ask for help. Most experienced editors are happy to guide you to better sources.

Bottom line: Use the source, not the platform

Don’t ask, "Can I cite this YouTube video?" Ask, "Is the information in this video backed by something reliable?"

If the answer is yes, cite the original report, article, or official document. If the answer is no, don’t use it. The platform doesn’t matter. The source does.

Wikipedia’s standards are strict. But they’re also simple: if you can’t verify it, don’t write it. That’s not a limitation-it’s the foundation of everything Wikipedia stands for.

Can I cite a YouTube video from a university channel on Wikipedia?

Yes, if the channel is officially run by the university and the video presents factual content like a lecture, interview, or research announcement. Always check that the video cites its own sources and that the university has a reputation for academic integrity. Videos from official university channels like MIT OpenCourseWare or Stanford Online are generally acceptable.

Are podcasts from NPR or BBC acceptable sources?

Yes. Podcasts produced by established news organizations like NPR, BBC, or The New York Times are considered reliable because they follow journalistic standards, have editorial oversight, and fact-check content. You can cite specific episodes when they report on verifiable events or feature interviews with experts who are cited elsewhere.

Can I use a tweet from a politician as a source?

Only in rare cases. A tweet from an elected official may be cited if it’s a direct, public statement on a matter of public record and no other reliable source exists. But even then, it’s better to cite a news article that reports on the tweet or the official transcript from a government website. Tweets are not primary sources-they’re secondary mentions.

Why can’t I cite a viral TikTok trend as evidence of public opinion?

Because TikTok trends reflect popularity, not accuracy or representativeness. Wikipedia requires sources that are independently verifiable and not driven by algorithmic amplification. A trend with millions of views might be misleading, fabricated, or culturally specific. Reliable sources for public opinion include peer-reviewed surveys, government polls, or studies from academic institutions.

What should I do if the only source I have is a podcast or YouTube video?

Don’t use it directly. Instead, find the original source behind the content. Did the podcast cite a study? Find the paper. Did the video feature an expert? Look up their published work. If the claim is important enough to include in Wikipedia, there should be a reliable, published source backing it. If not, the topic might not belong on Wikipedia yet.

If you’re editing Wikipedia and want to use modern media, remember: the medium doesn’t make the source reliable. The process does. Focus on who produced it, how it was reviewed, and whether it can be independently verified. That’s the only way to keep Wikipedia accurate-and useful-for everyone.