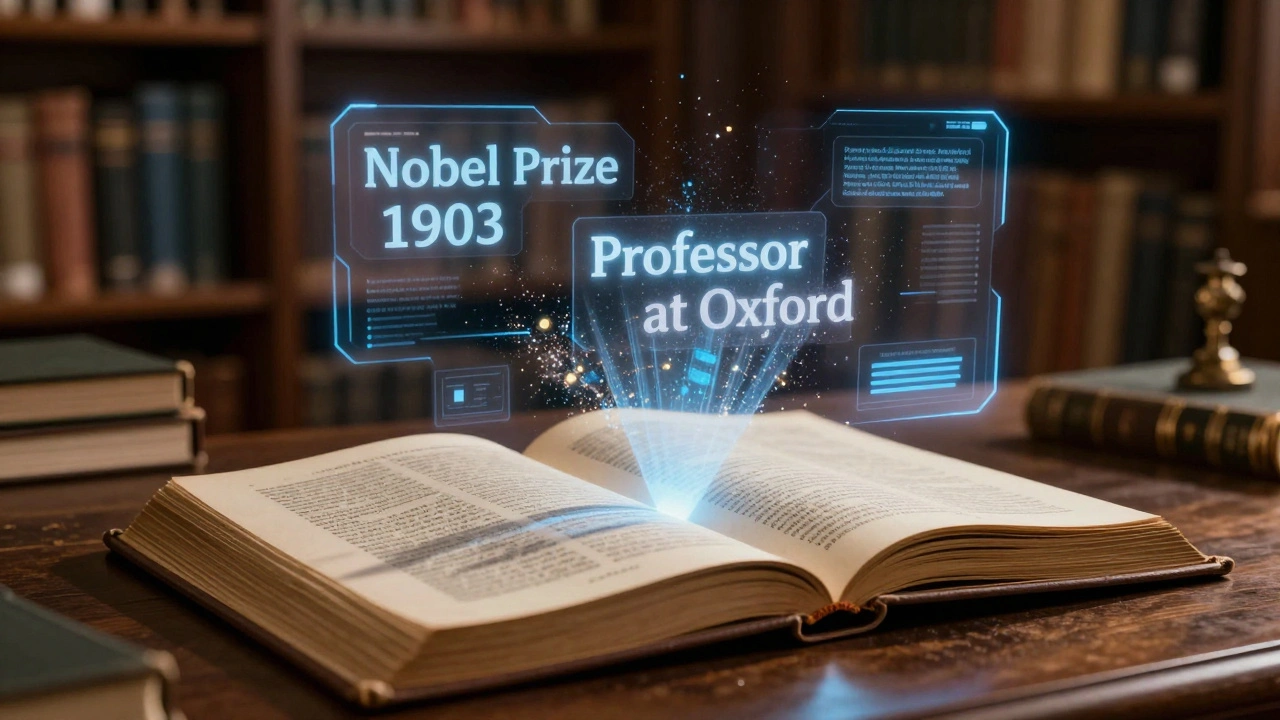

When you ask an AI encyclopedia for the birthdate of Marie Curie, it gives you the right answer: November 7, 1867. Simple. Clean. Trustworthy. But what if it tells you she won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1903 and Physics in 1911 - and adds that she was the first woman to serve as a professor at the University of Oxford? That last part is false. She never taught at Oxford. The AI didn’t make a typo. It hallucinated.

What Is an AI Hallucination?

An AI hallucination happens when a language model confidently generates information that sounds plausible but is completely made up. It’s not lying. It doesn’t have intent. It’s just guessing based on patterns it learned from millions of texts - including wrong Wikipedia edits, outdated blogs, and fictional stories buried in training data.

Think of it like a student who memorized every textbook but never went to class. They can write a detailed essay on quantum physics using phrases they’ve seen before - but when asked a specific question about an experiment no one ever did, they invent one. That’s AI hallucination.

These errors aren’t rare. A 2024 study by Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered AI found that top AI models hallucinated facts in 27% of responses when asked about historical events, scientific claims, or biographical details - the exact kind of information people expect from encyclopedias.

Why Encyclopedias Can’t Afford Hallucinations

Traditional encyclopedias like Britannica or Wikipedia survive because people trust them. They’re edited. They cite sources. They correct mistakes. When you look up the population of Tokyo, you expect a number backed by government census data - not a guess.

AI-powered encyclopedias like Perplexity, Elicit, or even Google’s AI Overviews are becoming popular because they answer questions fast. But speed doesn’t replace accuracy. If an AI encyclopedia tells you that the Eiffel Tower was built in 1899 instead of 1889 - and you cite that in a school paper - you’re wrong. And you won’t know why.

Unlike human editors, AI doesn’t know when it’s uncertain. It doesn’t say, “I’m not sure.” It says, “It was built in 1899.” And that’s dangerous.

The Ripple Effect on Trust

People don’t just use encyclopedias to learn. They use them to make decisions - medical, legal, educational, even personal. A parent researching vaccines. A student writing a thesis. A journalist fact-checking a quote. If AI hallucinations slip into these spaces, trust collapses.

One 2025 survey by Pew Research showed that 62% of users who encountered an AI-generated error in an encyclopedia lost confidence in all AI-sourced information - even if the rest was correct. That’s not just a glitch. That’s a credibility crisis.

Wikipedia has over 60 million articles, and humans correct 20,000 edits daily. AI doesn’t have that safety net. It doesn’t have a community. It doesn’t have peer review. It just outputs what it thinks sounds right.

How AI Encyclopedias Try to Fix This

Some companies claim they’ve solved hallucination by adding “source citations.” But citations don’t guarantee truth. An AI can cite a fake blog post that cites another fake blog post - and still sound legitimate.

Perplexity and Elicit now use retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), pulling facts from trusted databases before answering. That helps. But it’s not foolproof. If the source itself is outdated or wrong - like a Wikipedia page edited by a bot that got it wrong - the AI will repeat it.

Some AI encyclopedias now include a “confidence score” - a number between 0 and 100 that says how sure the AI is. But users rarely pay attention to it. And a score of 92 doesn’t mean the answer is right. It just means the AI feels confident.

Real fixes need more than tech. They need human oversight. The best AI encyclopedias now pair AI output with human fact-checkers. But that’s expensive. And slow. And most companies won’t pay for it.

What This Means for You

If you’re using an AI encyclopedia for school, work, or personal research, here’s what you need to do:

- Never accept an answer without checking the source.

- If the AI cites a website, go to that website yourself. Look for the original document or official data.

- Compare answers across two or three AI tools. If they disagree, assume all of them are suspect.

- For critical topics - health, law, history - always use a traditional, human-edited source first.

- Teach yourself to spot red flags: overly detailed claims, names you’ve never heard, dates that feel “off.”

There’s no button to turn off hallucinations. There’s no setting to make AI perfect. The only reliable tool you have is your own critical thinking.

The Bigger Picture

This isn’t just about encyclopedias. It’s about how we define truth in the digital age. For centuries, knowledge was stored in books, libraries, and experts. Now, it’s stored in algorithms trained on the internet - a place full of misinformation, bias, and noise.

AI encyclopedias promise access to all human knowledge. But they don’t have wisdom. They don’t understand context. They don’t know the difference between a myth and a fact - unless we teach them.

And right now, we’re letting them answer questions we don’t know how to verify.

Will AI Encyclopedias Replace Human-Edited Ones?

Not anytime soon. And maybe not ever.

Wikipedia’s model - open, collaborative, constantly corrected - is still unmatched. It’s messy. It’s slow. But when a mistake appears, someone fixes it within hours. AI doesn’t have that accountability.

AI can summarize. It can connect ideas. It can find patterns. But it can’t judge truth. Not yet. And maybe not ever without human oversight.

The future of reliable knowledge isn’t AI replacing humans. It’s humans using AI as a tool - not a teacher.

Can AI hallucinations be completely eliminated?

No, not with current technology. AI hallucinations come from how language models work - they predict the next word based on patterns, not facts. Even the most advanced models, like GPT-4o or Claude 3, still generate false information with surprising frequency. The best we can do is reduce them with better training data, source verification, and human review - but we can’t eliminate them entirely.

Are AI encyclopedias more prone to hallucinations than search engines?

Yes, because AI encyclopedias summarize and rephrase information, while search engines mostly link to existing pages. When you search for "who invented the telephone," Google shows you multiple sources. An AI encyclopedia might say, "Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone in 1876," and leave out the fact that Elisha Gray filed a similar patent the same day. The AI skips nuance to sound confident - which increases hallucination risk.

Why do AI encyclopedias sound so convincing even when they’re wrong?

AI is trained to sound like a human expert. It uses formal language, logical structure, and confident tone - even when it’s guessing. Studies show people trust text that’s well-written, regardless of accuracy. This is called the "authority bias." A poorly written correct answer might be ignored, while a polished wrong one gets believed.

Can I trust an AI encyclopedia for academic research?

Not as a primary source. Use AI encyclopedias only to get a starting point - to find names, dates, or concepts you can then verify with peer-reviewed journals, official publications, or human-edited encyclopedias like Britannica or Wikipedia. Never cite an AI-generated summary in a paper without checking the original source. Many universities now ban AI-generated citations for this reason.

Do all AI encyclopedias hallucinate the same way?

No. Models trained on more reliable data (like academic journals or verified databases) hallucinate less. Tools like Elicit, which pull from PubMed and JSTOR, are more accurate for scientific topics than general-purpose models like ChatGPT. But even the best ones still make mistakes. The key difference is not whether they hallucinate - it’s how often, and whether they cite sources you can check.