Wikipedia is built on sources. Not just any sources - but reliable sources that back up every claim. Among these, primary sources are often misunderstood. Some editors think they’re the gold standard. Others avoid them entirely, fearing bias or inaccuracy. The truth? Primary sources can be powerful - if you know when and how to use them.

What Exactly Is a Primary Source?

A primary source is original material created at the time of an event or by someone directly involved. Think: letters, diaries, raw survey data, court transcripts, original research papers, government documents, interviews, photographs, or even social media posts from eyewitnesses.

Contrast that with secondary sources - books, articles, documentaries, or Wikipedia itself - that analyze, interpret, or summarize primary material. A newspaper article describing a protest is secondary. A video filmed by someone at the protest? That’s primary.

On Wikipedia, primary sources aren’t banned. They’re regulated. The project doesn’t reject them outright. It just demands you use them right.

When Primary Sources Are Allowed - and When They’re Not

You can use primary sources on Wikipedia, but only under strict conditions.

- Allowed: When a secondary source isn’t available, and the primary source is authoritative and directly supports a factual claim.

- Not allowed: When you’re using a primary source to make an interpretation, analysis, or conclusion that hasn’t been verified by a reliable secondary source.

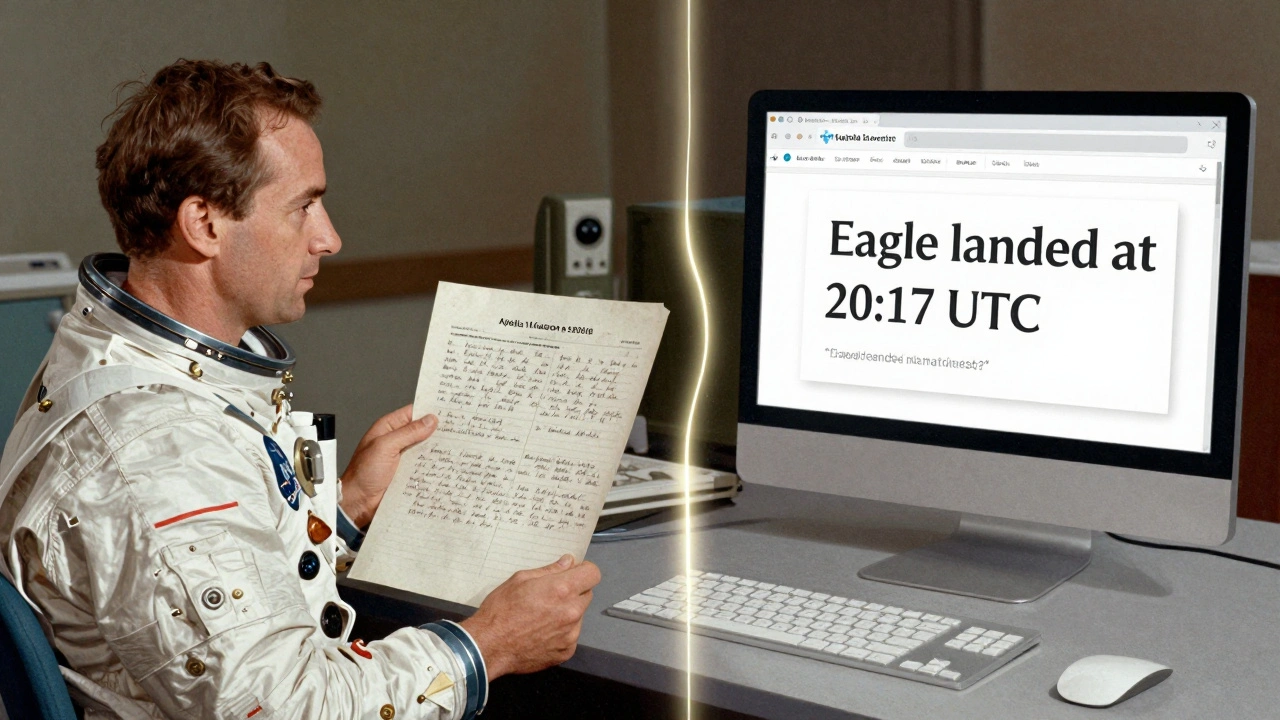

For example: If you’re writing about the 1969 moon landing, you can cite NASA’s original mission logs to confirm the exact time of the lunar module’s touchdown. That’s fine - it’s a direct, factual record.

But if you try to use the same logs to argue that the moon landing was staged? That’s a problem. Wikipedia doesn’t allow original research. Even if the source is primary, you can’t draw new conclusions from it.

Another example: A scientist publishes a peer-reviewed study showing a new drug reduces blood pressure. That’s a primary source. You can cite it to state the study’s findings. But if you then claim the drug is “safe for everyone,” that’s an interpretation - and you need a secondary source like a medical review or guideline to back it up.

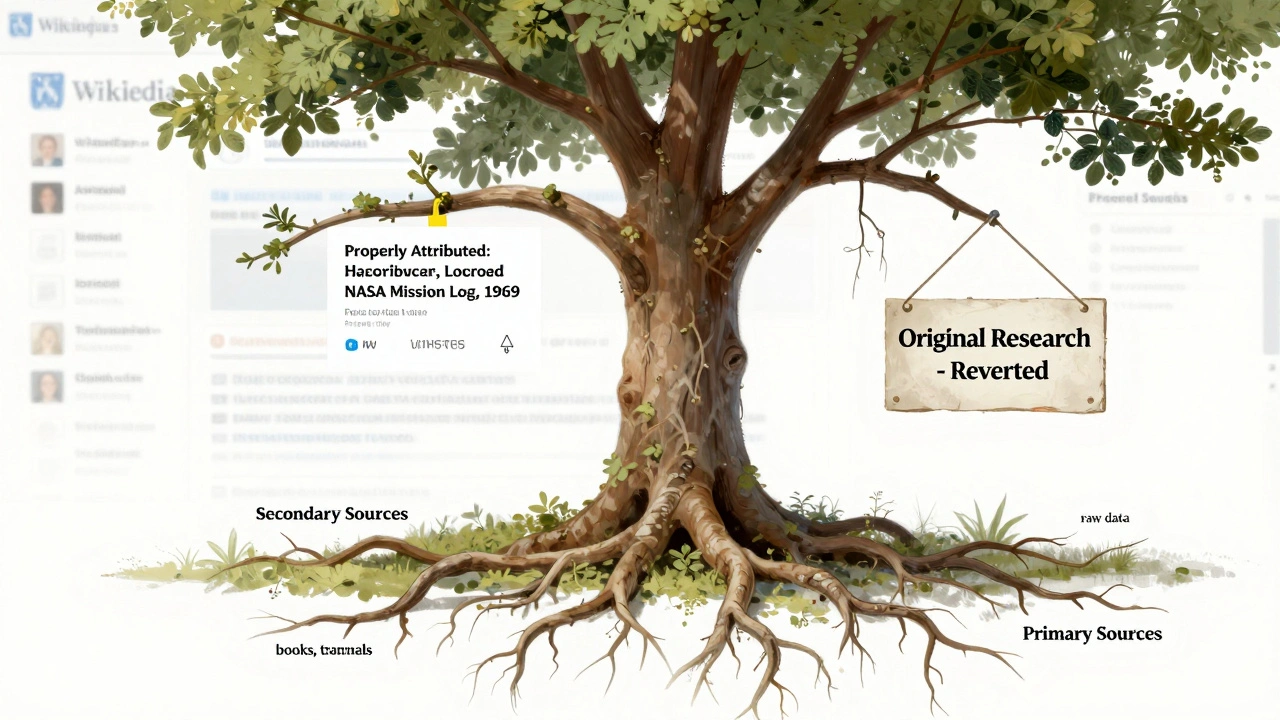

Why Secondary Sources Are Usually Better

Most Wikipedia articles rely on secondary sources because they’ve been vetted. A journal article, book, or reputable news report has gone through editorial review, fact-checking, or peer review. It’s already filtered out noise, bias, or errors.

Primary sources? They’re raw. They can be incomplete. Misleading. Or even fraudulent. A company’s press release isn’t the same as a report from the Associated Press. A blog post from a researcher isn’t the same as their published paper in The Lancet.

Wikipedia’s policy is clear: “Primary sources should not be used to make claims unless they are clearly reliable and directly support the claim without interpretation.” That’s why most editors prefer secondary sources. They’re safer, clearer, and less likely to trigger disputes.

When You Must Use a Primary Source

There are times when you have no choice. Here are the most common valid cases:

- Historical facts with no secondary coverage - Like citing a 19th-century census record to confirm a person’s birthplace when no modern book mentions it.

- Official records - Government data, court rulings, patents, or legislative texts. For example, citing the U.S. Constitution to quote Article I, Section 8.

- Direct quotes from participants - If you’re writing about a speech, and the only source is the speaker’s own transcript or video, you can cite that - but only to state what was said, not to interpret its meaning.

- Original research data in peer-reviewed journals - When summarizing results from a study, you cite the study itself. That’s standard practice in academic writing and accepted on Wikipedia.

In all these cases, you’re not making an argument. You’re reporting a fact directly from the source.

How to Attribute Primary Sources Correctly

Attribution isn’t just about giving credit. It’s about transparency. Readers need to know exactly what you’re citing and why it’s trustworthy.

Follow these steps:

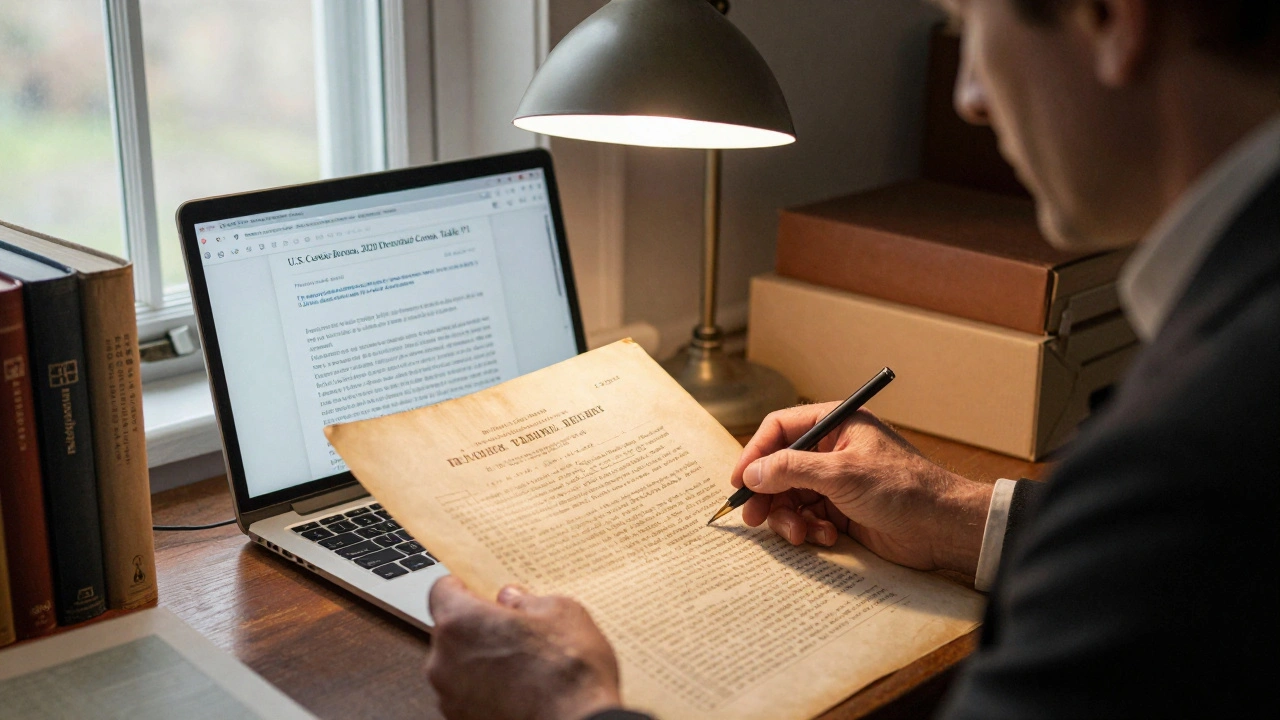

- Use the exact title and version - If citing a document, include the full title, version number, and date. “U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Decennial Census, Table P1” is better than “Census data.”

- Link to the original - If it’s online, use a direct link to the source. If it’s a book, give the ISBN. If it’s a video, link to the original upload.

- Specify the page or timestamp - Don’t just say “see the report.” Say “see page 42” or “at 12:37 in the video.”

- Clarify the source’s reliability - If the source is a government agency, say so. If it’s a personal blog, say that too. Don’t hide the context.

- Never paraphrase primary sources to fit your narrative - If you’re quoting a letter, quote it exactly. If you’re citing survey results, report the numbers as they appear.

Example of good attribution:

NASA’s official mission log for Apollo 11, published on July 20, 1969, states: “Eagle landed at 20:17 UTC.” This is cited in the article as: “NASA (1969). Apollo 11 Mission Log, p. 17.”

Bad attribution:

“The moon landing happened in 1969.” - No source given. Or worse: “Some people say the moon landing was real.” - That’s not a source. That’s speculation.

What Happens If You Use a Primary Source Wrong?

Wikipedia editors are trained to spot misuse. If you cite a primary source to support an interpretation, your edit will likely be reverted. You might get a warning. In extreme cases, your account could be flagged for original research violations.

Common mistakes:

- Using a company’s press release to claim their product is “the best on the market.”

- Citing a personal blog as proof of a historical event.

- Quoting a tweet from a politician and using it to define their political stance.

- Using raw survey data to conclude “most people agree” without statistical analysis.

These aren’t just bad edits - they break Wikipedia’s core policies: No Original Research and Verifiability.

How to Check If a Source Is Reliable

Before citing anything, ask:

- Who created it? Is it a government agency, university, reputable news outlet, or peer-reviewed journal?

- When was it published? Is it current? Outdated sources can mislead.

- Is it accessible? Can others verify it? A private email or internal memo isn’t verifiable.

- Does it have editorial oversight? Peer review? Fact-checking? Legal review?

- Is it neutral? Does it have a clear bias or agenda?

Wikipedia’s Reliable Sources page lists trusted publishers. If your source isn’t on that list, ask yourself: Would a professor, journalist, or librarian trust this?

What to Do When You Find a Primary Source That’s Perfect

Even if it’s perfect, don’t rush to add it. First, check if a secondary source already covers the same fact. If yes, use the secondary one. It’s easier to verify and less likely to cause conflict.

If no secondary source exists, and the primary source is solid, go ahead - but:

- Tag it clearly in the citation.

- Be ready to defend it in the article’s talk page.

- Consider adding a note: “This claim relies on a primary source due to lack of secondary coverage.”

That transparency builds trust.

Final Rule: When in Doubt, Use a Secondary Source

Wikipedia isn’t a platform for publishing raw data. It’s a summary of what’s already been verified by others. Your job isn’t to be the first to report something - it’s to report what’s already been reported by reliable sources.

Primary sources have their place. But they’re tools, not shortcuts. Use them carefully. Attribute them precisely. And never let them replace the need for context, verification, and balance.

If you’re unsure, ask on the article’s talk page. The Wikipedia community will help you decide - and they’ll thank you for asking instead of guessing.

Can I use a Wikipedia article as a primary source?

No. Wikipedia is a tertiary source - it summarizes secondary sources. You cannot cite Wikipedia as a primary source for any claim. Always go back to the original source Wikipedia references.

Are personal blogs ever acceptable as primary sources?

Only in rare cases - like if the blogger is a recognized expert and the blog is an official publication (e.g., a scientist’s lab blog with peer-reviewed posts). Most personal blogs are not reliable. Even if they contain firsthand accounts, Wikipedia requires verifiable, published material.

Can I cite a YouTube video as a primary source?

Yes - if it’s an original recording of an event, like a speech, interview, or live footage. But you must verify the uploader’s identity and the video’s authenticity. A random user’s reupload of a news clip doesn’t count. The original source matters.

Do I need to cite primary sources in the same format as secondary ones?

Yes. Wikipedia uses the same citation style for all sources: author, title, date, publisher, and location (page, timestamp, URL). The source type doesn’t change the format - but you must clarify its nature in the citation if it’s unusual (e.g., “Personal interview, 2024” or “NASA Mission Log, 1969”).

What if a primary source contradicts a widely accepted secondary source?

Don’t replace the secondary source. Instead, mention both in the article and explain the discrepancy. For example: “While most historians cite X as the cause, a newly discovered diary (Smith, 2023) suggests Y.” This preserves neutrality and invites further research.

If you’re editing Wikipedia and unsure about a source, pause. Ask yourself: Would this hold up in a college paper? If not, find a better one. The goal isn’t to be clever - it’s to be correct.