Wikipedia isn’t run by a team of paid professionals. It’s built by millions of people who log in, make edits, and click save-often with no reward, no recognition, and sometimes no thanks. So why do they do it? If you’ve ever wondered what drives someone to fix a typo in a 10-year-old article about Baltic geography or rewrite a paragraph on quantum entanglement, the answer isn’t simple. It’s not one thing. It’s three: altruism, expertise, and recognition.

Altruism: The Quiet Drive to Help

Most Wikipedia editors don’t edit because they want to be famous. They edit because they believe knowledge should be free-and that someone else might need it tomorrow. A 2023 study by the Wikimedia Foundation found that over 68% of active editors said their main reason for contributing was to help others learn. That’s not a small number. That’s the majority.

Think about the person who spends an hour correcting misinformation about a local school’s history. They don’t get paid. They don’t get a byline. They might not even be from that town. But they know that a student in another country might be using that page for homework. That’s the quiet power of altruism. It’s not dramatic. It’s not loud. But it’s the foundation of Wikipedia.

And it’s not just about big fixes. Sometimes it’s a single word. A missing comma. A broken link. These small edits add up. In 2024 alone, over 300 million edits were made to English Wikipedia. Most of them were minor. Most of them were done by people who just wanted to make things a little better.

Expertise: Sharing What You Know

Wikipedia attracts people who know something-and want to share it. A retired chemist fixes errors in articles about organic compounds. A high school teacher updates the timeline of the Civil Rights Movement. A software engineer corrects technical inaccuracies in articles about machine learning frameworks.

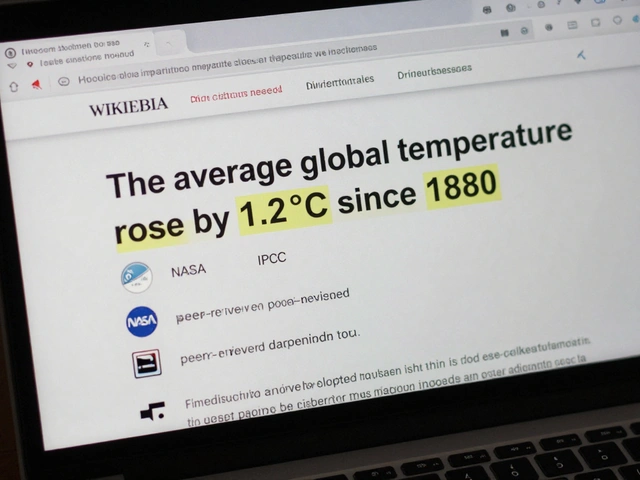

These aren’t hobbyists. They’re experts. And they’re not just correcting mistakes-they’re adding depth. A 2022 analysis of article quality showed that pages edited by users with verified professional backgrounds (like doctors, professors, or engineers) were 47% more likely to include citations from peer-reviewed sources.

There’s a reason Wikipedia has become a go-to for students and researchers: it’s often the most detailed, up-to-date source available. And that’s because people with real-world knowledge are putting in the work. You don’t need a degree to edit, but if you have one, Wikipedia gives you a way to use it-not for grades or promotions, but because you care about accuracy.

Some editors even build entire collections of articles around their specialty. One user, a historian of medieval trade routes, spent five years expanding and citing every article related to the Silk Road. He didn’t get paid. He didn’t get a title. But now, that content is used by universities around the world.

Recognition: The Invisible Badge of Honor

Here’s the twist: people edit Wikipedia for recognition-even though it’s mostly invisible.

There’s no public leaderboard. No trophy. No press release. But editors do get noticed-by other editors. A well-written article might earn a “Good Article” badge. A consistent contributor might get a “Barnstar,” a digital award given by peers. These aren’t official honors. But in the Wikipedia community, they mean something.

Think of it like a secret handshake. If you’ve been editing for years, other editors will recognize your username. They’ll trust your edits. They’ll ask you to review their work. That’s recognition-not from the public, but from the people who matter most: the community.

Some editors even keep personal logs of their contributions. One user in Berlin has tracked every edit since 2008. He doesn’t share it publicly. He just likes knowing he’s helped build something lasting. That’s a different kind of recognition: the quiet satisfaction of knowing your name is tied to something that outlives you.

The Overlap: When All Three Mix

The real magic happens when altruism, expertise, and recognition come together.

Imagine a nurse in rural India who notices that Wikipedia’s article on malaria prevention lacks details about local treatment protocols. She spends her evenings researching WHO guidelines, adding local context, and citing regional studies. Her edits are reviewed by a doctor in Canada. They’re praised by a student in Nigeria. She doesn’t know any of them. But she’s helped someone-and she’s now part of a global network of people who care about accurate health information.

This is how Wikipedia grows. Not through ads or algorithms, but through people who care enough to act. It’s not about being the best writer. It’s about being the one who notices something’s wrong-and does something about it.

Who Are These People?

Wikipedia editors aren’t a monolith. They’re students, retirees, librarians, programmers, stay-at-home parents, and professors. But they do share traits. A 2024 survey of 12,000 active editors found:

- 41% were between 25 and 34 years old

- 33% had at least a bachelor’s degree

- 56% edited at least once a week

- 72% said they’d never been paid to edit

Most of them live outside the U.S. and Europe. The fastest-growing group of editors is in Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. They’re not just consuming Wikipedia-they’re shaping it.

Why This Matters

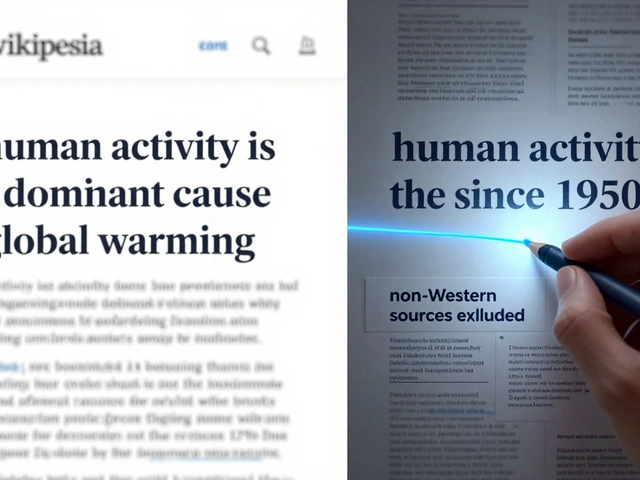

Wikipedia is the fifth most visited website in the world. Over 2 billion people use it every month. And yet, fewer than 1% of those users ever edit it. That’s a problem. Because if only a small group shapes what billions read, the knowledge base becomes skewed.

Who gets to write history? Who decides what’s important? Who corrects the bias? The answer is: whoever shows up. And right now, that’s mostly people who are motivated by the same three things: the desire to help, the urge to share what they know, and the quiet need to be seen by others who care.

Wikipedia doesn’t need more users. It needs more contributors. Not because it’s broken-but because it’s alive. And it only stays alive because people like you and me keep showing up to fix it, one edit at a time.

Do Wikipedia editors get paid?

No, the vast majority of Wikipedia editors are volunteers. The Wikimedia Foundation, which supports Wikipedia, pays a small staff to manage servers and legal issues-but not to write or edit content. Over 95% of edits are made by unpaid contributors motivated by altruism, expertise, or community recognition.

Can anyone edit Wikipedia, even without expertise?

Yes, anyone can edit. But edits from people without expertise are often reviewed and corrected by others. Wikipedia’s system relies on community oversight. A beginner might fix a spelling error, while a subject expert adds citations. Both are valuable. The platform doesn’t require credentials-it just requires accuracy and good faith.

Why do some edits get reverted?

Edits are reverted when they violate Wikipedia’s core policies: no original research, no biased language, and no unverified claims. A well-intentioned edit might be removed if it adds opinion, lacks a source, or contradicts reliable references. This isn’t punishment-it’s quality control. Reversion is often followed by a discussion, helping new editors learn the rules.

Is Wikipedia editing a form of activism?

For some, yes. Editing can be a way to challenge systemic bias-like adding information about underrepresented groups, correcting colonial narratives, or including sources from non-Western perspectives. Many editors see knowledge equity as a social justice issue. Fixing a biased sentence isn’t just editing-it’s correcting history.

How do I start editing Wikipedia?

Start small. Find a page with a typo or missing citation. Click “Edit,” make your change, add a brief edit summary like “Fixed spelling,” and save. You don’t need approval. You don’t need permission. Just follow the guidelines. The community will help you learn as you go.

If you’ve ever thought about editing Wikipedia but held back because you didn’t feel qualified, remember this: you don’t need to be an expert to make a difference. You just need to care enough to try. One edit can change how someone understands the world.