Wikipedia runs on a simple idea: anyone can edit it. That’s it. No approval process. No corporate editors reviewing every change. No hierarchy of writers with final say. And yet, it’s the fifth most visited website in the world, with over 60 million articles in 300+ languages. How does it work without top-down control?

It’s Not Chaos - It’s Emergent Order

People assume that without editors in charge, Wikipedia would be a mess. But it’s not. It’s organized - not by managers, but by norms. The rules aren’t written in a boardroom. They’re written in plain sight, on talk pages and policy wikis, shaped by thousands of volunteers over two decades.

Take verifiability. You can’t just write, "The moon is made of cheese." You need to cite a reliable source. That’s not a rule handed down from above. It’s a practice that emerged because editors kept reverting nonsense, and eventually, everyone agreed: if it’s not cited, it doesn’t belong. The system self-corrects.

And it’s not perfect. But it’s better than you think. A 2021 study from the University of Minnesota found that Wikipedia’s accuracy on scientific topics matches or exceeds that of Encyclopedia Britannica. Not because someone checked every article. Because thousands of people kept checking each other.

No Bosses, Just Process

Wikipedia has no CEO. No editorial board. No staff deciding what gets published. The Wikimedia Foundation exists to keep the servers running and handle legal issues - not to edit content. That’s the key.

Instead of control, Wikipedia uses process. If you disagree with an edit, you don’t complain to a manager. You start a discussion on the article’s talk page. You cite policy. You bring in other editors. You wait. If the community agrees with you, the edit changes. If not, it stays.

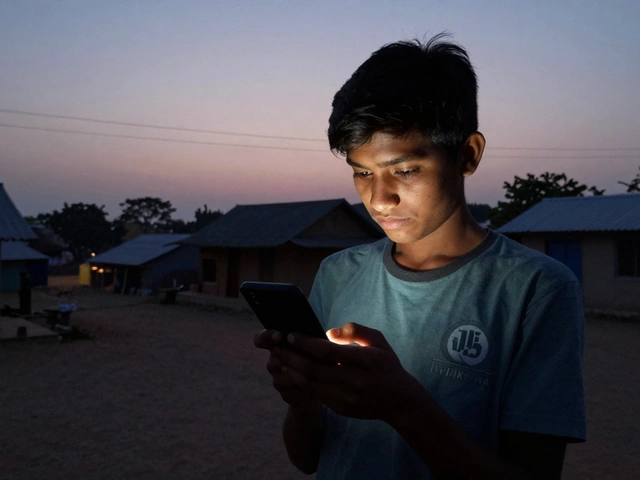

This sounds slow. And sometimes it is. But it’s also fair. A farmer in Kenya, a high school student in Brazil, and a retired professor in Canada all have the same power to change a line about climate change. No one gets special treatment because of their job title.

Why Top-Down Control Would Break It

Imagine if Wikipedia had editors in New York deciding what gets published in Hindi, Arabic, or Swahili. They wouldn’t know local context. They’d miss cultural nuances. They’d accidentally erase knowledge that matters to communities outside the Western world.

Take the article on "Traditional medicine in Nigeria". If a top-down editor from London rewrote it using only Western medical sources, they’d strip out centuries of local knowledge. But local editors - people who’ve seen their grandparents use herbal remedies - know what’s real. They cite community elders, oral histories, field studies. That’s the kind of knowledge top-down systems kill.

Top-down control also creates bottlenecks. Who would edit 60 million articles? Even if Wikipedia hired 10,000 editors, they couldn’t keep up. The platform grows because everyone can help. A single person can fix a typo in a 10,000-word article on quantum physics at 2 a.m. - and no one needs to sign off.

The Hidden Structure: Policies, Not People

Wikipedia doesn’t rely on authority. It relies on policy. There are hundreds of them. Neutral point of view. No original research. Reliable sources. Assume good faith.

These aren’t suggestions. They’re enforced - by bots, by experienced editors, by community consensus. A bot can revert vandalism in seconds. A veteran editor can flag a biased rewrite. A group of editors can vote to semi-protect an article if it’s under constant attack.

And here’s the trick: you don’t need to be a "trusted editor" to use these tools. Any registered user can propose a policy change. Anyone can join a discussion. The system rewards participation, not titles.

That’s why Wikipedia survives. Not because it’s perfect. But because it’s open enough to let people fix it - without waiting for permission.

What Happens When You Try to Control It?

There have been attempts. In 2012, the Chinese government tried to force Wikipedia to remove articles on sensitive topics. Wikipedia didn’t comply. Instead, it let local editors decide what to keep. The result? Articles on those topics were rewritten with more local sources, not deleted.

In 2017, a major news outlet tried to pay editors to promote their story on Wikipedia. The community caught it. The editors were blocked. The article was locked. The story was buried under scrutiny - not by a corporate team, but by ordinary users who noticed the pattern.

Even when big organizations try to take over, the system pushes back. Because control doesn’t come from the top. It comes from the bottom - from the people who care enough to show up, day after day.

It’s Not About Being Perfect - It’s About Being Alive

Wikipedia isn’t a finished product. It’s a living document. A car repair manual that gets updated every time someone fixes a new model. A history textbook rewritten every time a new archive opens.

That’s why it’s so powerful. You don’t need to be an expert to contribute. You just need to care. Maybe you noticed a typo in the article about your hometown. Maybe you added a citation from your grandfather’s diary. Maybe you fixed a broken link on a page about endangered birds in your country.

Those small acts add up. And they’re why Wikipedia doesn’t need bosses. It needs people - real people - who show up, argue politely, cite sources, and keep going even when no one’s watching.

What Holds It Together?

Three things: transparency, trust, and repetition.

Transparency - Every edit is public. Every discussion is archived. You can see who changed what, when, and why. No secret meetings. No backroom deals.

Trust - You trust that someone else will fix your mistake. You trust that others will catch your bias. You trust that the system works, even if you don’t understand how.

Repetition - The same policies are used over and over. The same tools are reused. The same patterns emerge. That’s how norms become habits.

It’s not magic. It’s mechanics. And it works - at a global scale - because it doesn’t try to control. It tries to enable.

Can This Model Work Elsewhere?

People try. Governments want to copy Wikipedia for public records. Corporations want to use it for internal knowledge bases. But most fail. Why?

Because they try to add control. They add managers. They add approvals. They add roles. And then the energy dies.

Wikipedia works because it removes barriers. Not because it’s flawless - because it’s forgiving. You can mess up. You can be wrong. You can be new. You can come back tomorrow and try again.

That’s the real secret. It’s not about having the best editors. It’s about letting anyone become one.