Wikipedia runs on trust. Millions of edits happen every day, and most are honest. But some aren’t. Vandalism shows up fast - a fake quote on a celebrity’s page, a racist slur on a history article, or a whole page replaced with nonsense. The system doesn’t rely on robots alone. It leans on human editors using a tool called CheckUser to find patterns behind the chaos.

What CheckUser Actually Does

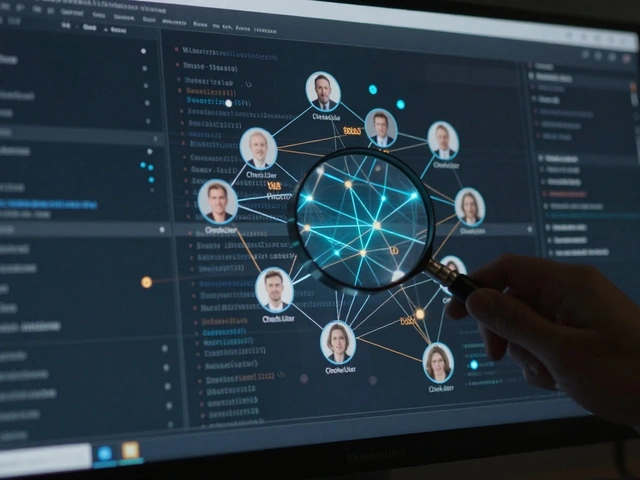

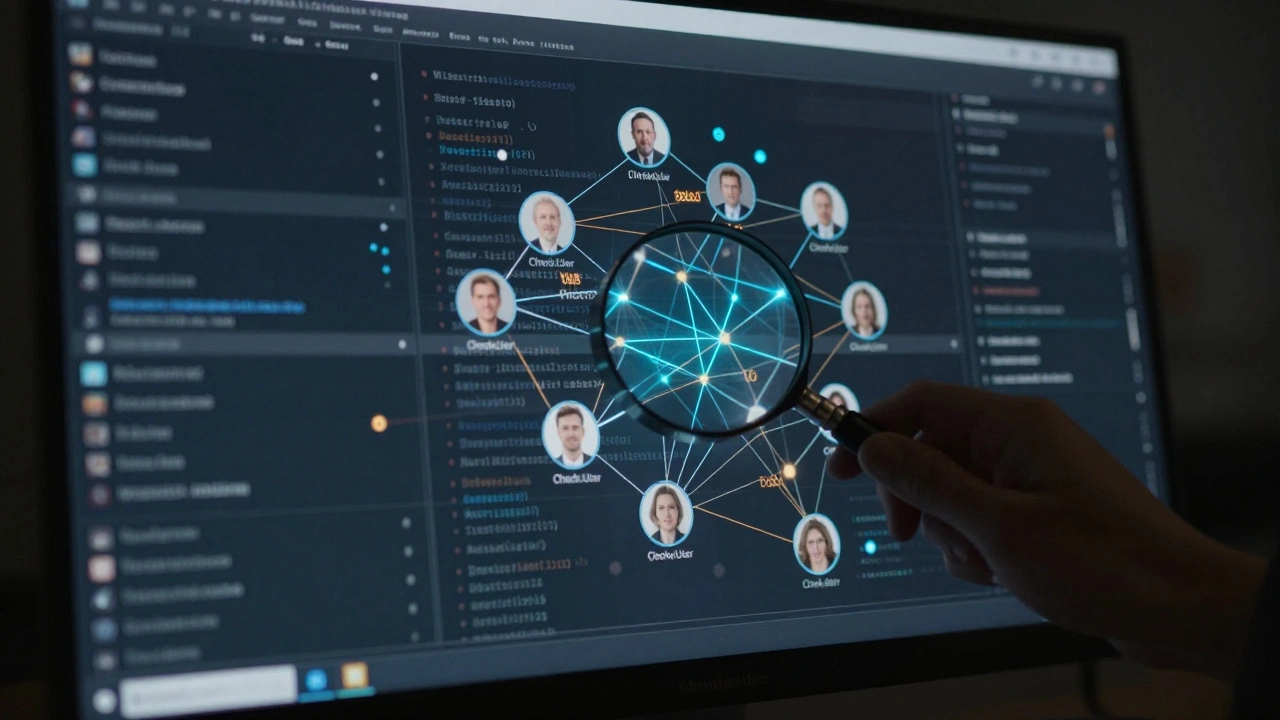

CheckUser isn’t a surveillance tool. It’s a forensic aid. Only a small group of trusted volunteers - called CheckUsers - have access to it. Their job? To see if multiple accounts are linked to the same person or device. Think of it like a detective checking if the same person is using different aliases to cause trouble.

When someone reports a suspected sockpuppet - an account created to evade a block - a CheckUser can look at technical fingerprints: IP addresses, browser fingerprints, connection times, and network routes. If two accounts from different continents suddenly start editing the same article at 3 a.m. UTC, that’s a red flag. If they use identical misspellings or the same odd phrasing, that’s even more telling.

CheckUser doesn’t tell you who someone is in real life. It doesn’t reveal names, addresses, or phone numbers. It only shows connections between accounts. That’s intentional. Wikipedia protects privacy, even when dealing with vandals.

The Data You Can’t See

There’s a big gap between what CheckUser can do and what the public knows. Most users never see the tool’s output. Even editors without CheckUser access can’t see the full picture. That’s by design.

For example, if a vandal edits from a public library’s Wi-Fi, CheckUser might show 15 different accounts tied to that IP. But that doesn’t mean 15 people are vandalizing. Maybe it’s one person, or maybe it’s a shared network with hundreds of users. The tool can’t tell the difference. That’s a major limit.

Another blind spot: mobile data. If someone edits from a smartphone using cellular data, their IP changes every time they switch towers. CheckUser sees that as multiple IPs - not one user. So a single vandal could look like dozens of different people.

And then there’s Tor. Some vandals use anonymity networks to hide their tracks. CheckUser can detect Tor exit nodes, but it can’t link them to a real person. That means a lot of suspicious activity just… disappears into the noise.

How Vandalism Patterns Reveal Themselves

Even with limits, patterns emerge. CheckUsers have noticed that certain types of vandalism cluster in predictable ways.

- Politically motivated edits spike around elections - often from the same few IP ranges.

- Corporate PR teams sometimes edit their own company pages, then create new accounts to defend those edits. CheckUser spots the link between the original edit and the "defender" accounts.

- Some vandals target specific topics - like sports teams or pop stars - and use the same signature phrasing every time. That’s easier to catch than random spam.

Wikipedia’s public edit history helps too. Tools like WikiScanner (now retired) once let anyone see which organizations were editing articles. Today, similar patterns are tracked by volunteers using custom scripts. They don’t need CheckUser - just time, patience, and a sharp eye.

Why CheckUser Isn’t a Magic Bullet

Some people think CheckUser should be used more often. But it’s not that simple.

First, it’s slow. Running a CheckUser request takes time. Volunteers have to review logs, compare timestamps, and sometimes wait for data to sync. It’s not instant.

Second, false positives happen. Two people in the same household might edit Wikipedia. A student might use a university network that dozens of others use. A vandal could be the only one in a shared apartment, but their edits look like they came from a dozen people.

Third, there’s the risk of abuse. If CheckUser were widely available, someone could use it to harass editors - for example, by falsely accusing a rival of being a sockpuppet. That’s why access is limited to about 200 editors worldwide, all vetted by the Wikimedia Foundation.

Even then, mistakes happen. In 2023, a CheckUser mistakenly linked a long-term editor to a banned user because both used the same public library’s Wi-Fi. The editor was cleared after a week of review. But the damage to trust was done.

What Happens After CheckUser Finds Something

Finding a link isn’t the end. It’s just the start.

If CheckUser confirms multiple accounts are linked to one person, the next step is usually a global block. That means all those accounts are locked from editing any Wikipedia language. But if the person is just a repeat vandal - not a troll or a bot - they might get a warning instead.

Some vandals are repeat offenders. One user, known only by their IP, was blocked over 150 times between 2019 and 2025. Each time, they came back with a new account. CheckUser helped confirm it was the same person. Eventually, their home IP was blocked from editing entirely.

But even blocks aren’t perfect. Some vandals switch countries. Others use public computers. A few even pay for proxy services. The cat-and-mouse game never ends.

Alternatives to CheckUser

Not every edit needs a CheckUser request. Most vandalism gets caught before it even spreads.

- Revert bots like ClueBot NG undo obvious vandalism in seconds.

- Watchlists let editors monitor pages they care about. A single editor watching 500 pages can catch more than a dozen automated tools.

- Recent Changes Patrol is a real-time stream of edits. Volunteers scan it for odd patterns - sudden capitalization, nonsense words, or edits that don’t match the article’s tone.

- Community reports are still the most reliable. If ten editors all say, "This edit looks fake," it’s probably fake.

CheckUser is the last line of defense - not the first. It’s used when the pattern is too complex for bots or too quiet for casual editors to notice.

The Bigger Picture: Trust, Not Control

Wikipedia’s real strength isn’t its tools. It’s its community. CheckUser helps, but it doesn’t run the site. Humans do.

The system works because most people want to help. Even vandals are often just kids or trolls - not master hackers. The goal isn’t to catch every single one. It’s to make it too hard to keep doing it.

That’s why transparency matters. Every CheckUser action is logged. Every block is public. Every decision can be challenged. If you think you were wrongly blocked, you can appeal. If you think a CheckUser made a mistake, you can ask for review.

It’s messy. It’s slow. It’s imperfect. But it’s honest. And that’s why Wikipedia still works - even with 1.5 billion monthly visitors and thousands of vandals trying to break it every day.

Can anyone use CheckUser on Wikipedia?

No. Only about 200 trusted volunteers, called CheckUsers, have access. They’re selected by the Wikimedia Foundation after a strict review process. Regular editors, even admins, can’t use it. Requests are made through a private channel and reviewed by other CheckUsers before action is taken.

Does CheckUser reveal real names or addresses?

No. CheckUser only shows technical data: IP addresses, connection patterns, and device fingerprints. It doesn’t access personal information like names, emails, or physical locations. Even if it links multiple accounts, it doesn’t say who the person is - only that they’re likely the same person behind different accounts.

Why don’t bots handle all vandalism instead of CheckUser?

Bots are great at spotting obvious spam - like random links or nonsense text. But they can’t understand context. A vandal might change "World War II" to "World War III" in a serious article, and a bot might miss it. Or they might edit subtly - changing a single fact to mislead. Only humans, with context and pattern recognition, can catch those cases. CheckUser helps humans connect the dots bots can’t see.

How often is CheckUser used to block vandals?

CheckUser requests are rare - only about 500-800 per month across all Wikipedia languages. Most of these are for sockpuppet investigations, not random edits. The majority of vandalism is caught by bots or community editors before it ever reaches CheckUser. It’s a last-resort tool, not a daily one.

Can CheckUser be used to target editors for personal reasons?

It’s possible, but very hard. All CheckUser requests are logged and reviewed by other volunteers. If someone tries to misuse it - like falsely accusing an editor of being a sockpuppet - it’s usually caught quickly. Repeated misuse can lead to loss of CheckUser access. The system is designed to protect against abuse, not enable it.