Wikipedia doesn’t have a CEO. It doesn’t have a board of directors making top-down decisions about what gets published. Instead, it’s run by volunteers - people who show up, edit articles, argue over citations, and sometimes block each other for days over whether a comma belongs in a sentence about a 19th-century economist. That’s community governance. And it works - not perfectly, but better than most expect.

Compare that to a corporate encyclopedia like Encyclopædia Britannica, which used to be printed in leather-bound volumes and now lives behind a paywall. Its editors are hired professionals. They follow style guides, answer to managers, and are accountable to shareholders. Their goal isn’t just accuracy - it’s brand consistency, legal safety, and revenue. That’s corporate editorial control.

Who decides what’s true?

On Wikipedia, anyone can edit. That’s the rule. But the reality is more nuanced. A new user can’t just delete a 20,000-word article on climate change and replace it with a rant about flat Earth. The system has layers. There are semi-protected pages, administrator flags, edit filters, and bots that roll back vandalism within seconds. Most edits are small: fixing typos, adding a source, updating a date. The big changes? They go through discussion pages. Talk pages. Hundreds of them.

Imagine a dispute over whether a historical figure was a hero or a villain. On Wikipedia, editors cite reliable sources - peer-reviewed journals, books from university presses, major newspapers. They don’t vote. They don’t poll. They debate based on evidence. If a source is weak, someone calls it out. If a pattern emerges of biased editing, admins step in. It’s messy. It’s slow. But it’s transparent. Every edit is logged. Every argument is archived.

Corporate editors don’t have that luxury. At Britannica, a single editor might decide whether a topic gets covered, how it’s framed, and which sources are deemed acceptable. That editor answers to an editorial director, who answers to a publisher. There’s no public log of why a sentence was changed. No discussion thread. No transparency. You get one version - the version approved by the company.

What happens when bias creeps in?

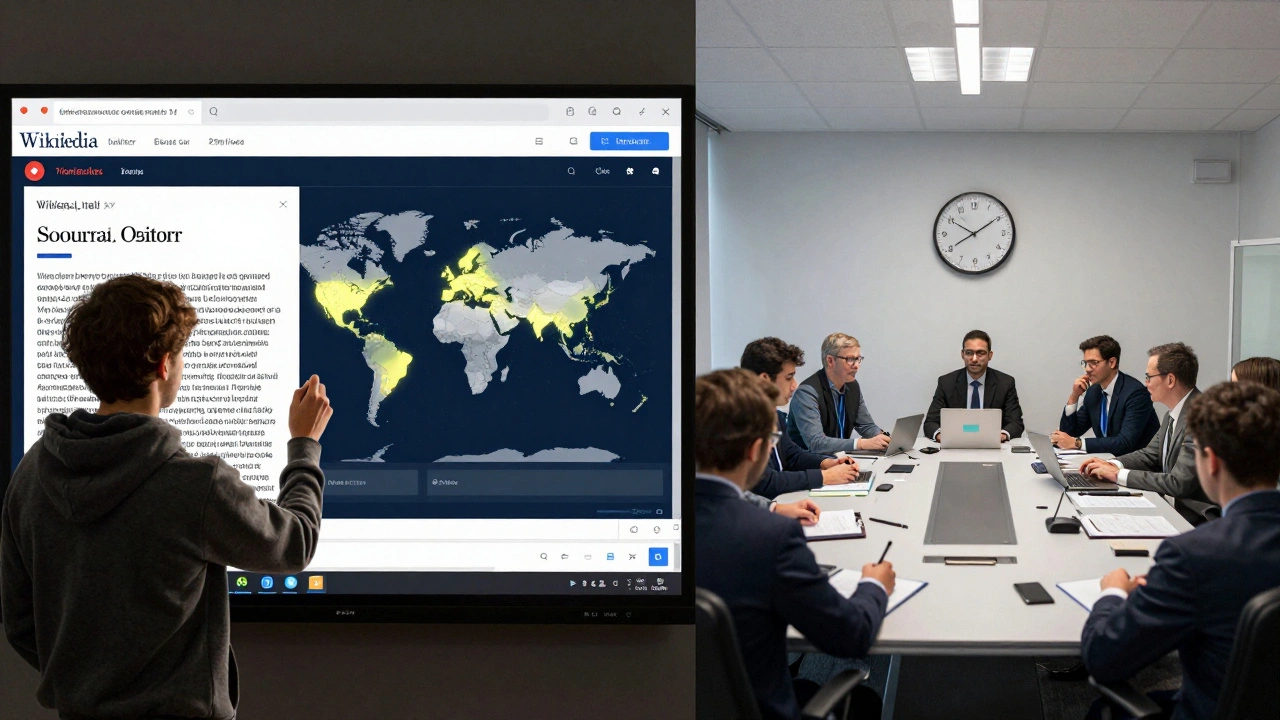

Wikipedia has bias. Everyone admits it. But it’s not hidden. It’s visible. You can see which editors are active, which sources they rely on, which topics get ignored. A 2020 study from the University of Oxford found that Wikipedia articles on political topics in the U.S. showed a slight left-leaning tilt - but only because more left-leaning editors showed up to edit them. The system didn’t force that. It just let it happen - and then allowed others to correct it.

Corporate systems are less visible. In 2018, a researcher found that Britannica’s entry on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict used language like "terrorism" far more often than Wikipedia’s, which stuck closer to neutral terms like "armed conflict." Why? Because Britannica’s editors, trained in Western academic traditions, were more likely to accept U.S. and Israeli government sources as authoritative. Wikipedia’s editors, from dozens of countries, pushed back with sources from Arab, European, and international media. The result? A more balanced article.

Corporate control doesn’t mean bias is absent - it just means it’s centralized. One person, one team, one policy. Community governance means bias is distributed. It’s harder to fix, but easier to spot. And because it’s public, it’s also easier to challenge.

Speed vs. stability

When a major event happens - say, a celebrity dies or a natural disaster strikes - Wikipedia updates in minutes. Volunteers monitor news feeds, pull verified reports, and edit live. Within an hour, the article has a timeline, photos, and links to official sources. It’s not perfect. Sometimes it’s wrong. But corrections come fast.

Corporate encyclopedias move slower. Britannica’s editorial process requires multiple rounds of review, legal clearance, and formatting checks. It can take weeks to update a single entry. In 2023, when the death of a prominent tech CEO made global headlines, Wikipedia had a full, sourced article up in 12 minutes. Britannica’s digital version didn’t update until three days later.

Speed isn’t always good. But in today’s world, where misinformation spreads faster than facts, Wikipedia’s agility matters. Corporate systems prioritize polish over speed. Wikipedia prioritizes access over perfection.

Who pays the bills?

Wikipedia doesn’t sell ads. It doesn’t charge users. It doesn’t take venture capital. It’s funded by donations - $100 million a year, mostly from small contributions from people around the world. That independence is critical. No advertiser can pressure it to soften a critical article. No investor demands higher engagement metrics.

Corporate encyclopedias? They’re businesses. Britannica is owned by a private equity firm. Its parent company also sells educational software to schools. That creates pressure: content must appeal to institutions, avoid controversy, and align with curriculum standards. A 2022 internal leak from another corporate knowledge platform showed editors being told to "avoid politically sensitive language" in entries about race and gender - not because the facts were wrong, but because it might upset school districts.

Wikipedia’s funding model means it can be controversial. It can say uncomfortable things. It can change its mind. Corporate systems can’t. They have to protect their market.

What breaks?

Wikipedia has had its failures. The infamous Seigenthaler biography hoax in 2005 - where a fake article falsely linked a journalist to the Kennedy assassination - exposed how vulnerable the system was. But it also showed how it self-corrects. The hoax was found within days. The editor who created it was banned. The article was locked. The incident led to new protections for biographies of living people.

Corporate systems rarely have public failures. When they do, they’re buried. In 2021, a major corporate knowledge base quietly removed all references to a whistleblower’s testimony after a lawsuit threat. No public explanation. No edit history. Just gone.

Wikipedia’s flaws are public. That’s its strength. You know what’s broken because you can see it. Corporate systems hide their mistakes behind NDAs and internal policies.

Which model wins?

Neither is perfect. But they serve different needs.

If you want a quick, open, evolving reference - one that reflects the real world as it’s understood by people across cultures and languages - Wikipedia wins. It’s not authoritative in the traditional sense. It’s participatory. It’s a living document.

If you want a polished, consistent, legally safe product that won’t surprise you - and you’re willing to pay for it - corporate control makes sense. It’s the encyclopedia your school district trusts because it’s predictable.

But here’s the thing: most people don’t realize Wikipedia is the default for 90% of online searches. When you Google "who invented the telephone?" or "what is quantum computing?" - you’re not reading Britannica. You’re reading Wikipedia. And you’re reading it because it’s faster, richer, and more detailed - even if it’s not always flawless.

Community governance doesn’t mean chaos. It means accountability through openness. Corporate control doesn’t mean quality. It means control.

Wikipedia’s model isn’t just about encyclopedias. It’s about how knowledge should be built in the digital age - by many, not by a few. And for now, that’s the version the world is using.

Can anyone really edit Wikipedia?

Yes, anyone can edit most articles without an account. But high-traffic or controversial pages are protected - meaning only registered users or experienced editors can make changes. New users are often restricted from editing sensitive topics until they’ve built trust through smaller edits. The system relies on community oversight, not locks.

Why doesn’t Wikipedia have professional editors like Britannica?

Wikipedia does have professional editors - but they’re volunteers, not employees. A few paid staff work for the Wikimedia Foundation on technical and legal issues, but no one is paid to write or approve articles. The content comes from volunteers with expertise - scientists, historians, journalists, and hobbyists. This keeps the project independent and avoids corporate influence.

Is Wikipedia less reliable than corporate encyclopedias?

Studies show Wikipedia is as accurate as Britannica on most scientific and historical topics. A 2005 Nature study found only four serious errors in Wikipedia’s science entries compared to three in Britannica. The difference isn’t accuracy - it’s transparency. Wikipedia’s errors are public and fixable. Corporate encyclopedias correct mistakes quietly, often without public notice.

Can corporations influence Wikipedia?

Yes, but it’s risky. Companies sometimes pay editors to promote their products or erase negative coverage. These edits are called "paid advocacy," and they’re against Wikipedia’s rules. When caught, accounts are banned. The community is highly suspicious of corporate behavior. A 2023 investigation found over 200 corporate-linked accounts removed for covert editing - and that’s just what was detected.

Why do people still use Britannica if Wikipedia is free and detailed?

Some institutions - schools, libraries, law firms - prefer Britannica because it’s legally safer. It has clear liability protections, consistent formatting, and no risk of sudden edits. For formal citations or classroom use, that predictability matters. But for everyday learning, most users prefer Wikipedia’s depth and speed.