Most people think they know Wikipedia. You type in a name, click the first result, skim a few paragraphs, and move on. But beneath the surface of those familiar articles lies a world of oddities, surprises, and stories that even regular users never see. Wikipedia isn’t just a collection of facts-it’s a living archive of human curiosity, edited by millions, full of quirks that feel like secrets whispered between strangers.

The longest Wikipedia article isn’t about a person or a war

It’s about list of countries by population. Not the countries themselves, but the list that ranks them. As of 2025, that single article has over 1.2 million words-longer than Moby-Dick and nearly as long as the entire English Wikipedia entry on World War II. Why? Because every single country, territory, and disputed region is tracked, updated in real time, and cited with sources from the UN, World Bank, and national censuses. It’s updated daily. Someone, somewhere, checks the population of Tuvalu or the Falkland Islands every few hours. That’s not just editing. That’s obsession.

There’s a Wikipedia page for a single letter

Yes, the letter Q has its own page. Not because it’s important linguistically, but because it’s the only letter in the English alphabet that doesn’t appear in the name of any U.S. state. That’s not why the page exists, though. The real reason? It’s a placeholder for words that start with Q but have no standalone article. The page lists everything from quasar to qat to qanat, and even includes the Q emoji. It’s a linguistic graveyard for oddities. And yes, it’s been edited over 12,000 times.

The most edited article on Wikipedia is not about politics or celebrities

It’s about George W. Bush. For years, it held the record. But since 2020, the top spot belongs to COVID-19 pandemic. Over 300,000 edits since January 2020. That’s more than one edit every 30 seconds during the peak of the crisis. Contributors from every continent, every language, every background-doctors, students, retirees-fought over data, sources, wording, and tone. One edit added a footnote citing a tweet. Another removed it. Another changed "mortality rate" to "case fatality rate" because of a WHO guideline update. This wasn’t just information. It was history being written in real time, by strangers who didn’t know each other.

Wikipedia has a page about itself being wrong

It’s called Wikipedia:List of mistakes. Not a joke. Not satire. A real, maintained page that catalogs documented errors that were once published and later corrected. One entry: "The article on the French Revolution once claimed it began in 1788." Another: "The page for the Eiffel Tower stated its height as 312 meters for seven years, even though it was 300 meters." There’s even a section for "persistent misconceptions," like the myth that Napoleon was short (he was actually average height for his time). The page doesn’t shame the mistakes. It celebrates the system working. Every error fixed is proof the community is paying attention.

There’s a Wikipedia article written entirely in Klingon

Yes, the language from Star Trek has its own Wikipedia edition. Not just a few pages-over 40,000 articles, all written in Klingon. The entire site runs in tlhIngan Hol. You can read about the Klingon Empire, Klingon cuisine (gagh, anyone?), and even a detailed breakdown of the Klingon calendar. The project started in 2004. Today, it’s one of the most active non-English Wikipedias by edits per capita. Why? Because the people who built it weren’t fans. They were linguists. They treated Klingon like Latin-dead, but still studied. The grammar rules were reverse-engineered from TV scripts. The vocabulary was expanded by volunteers who wrote poetry in it. It’s the most dedicated fan project in history… that also happens to be academically valid.

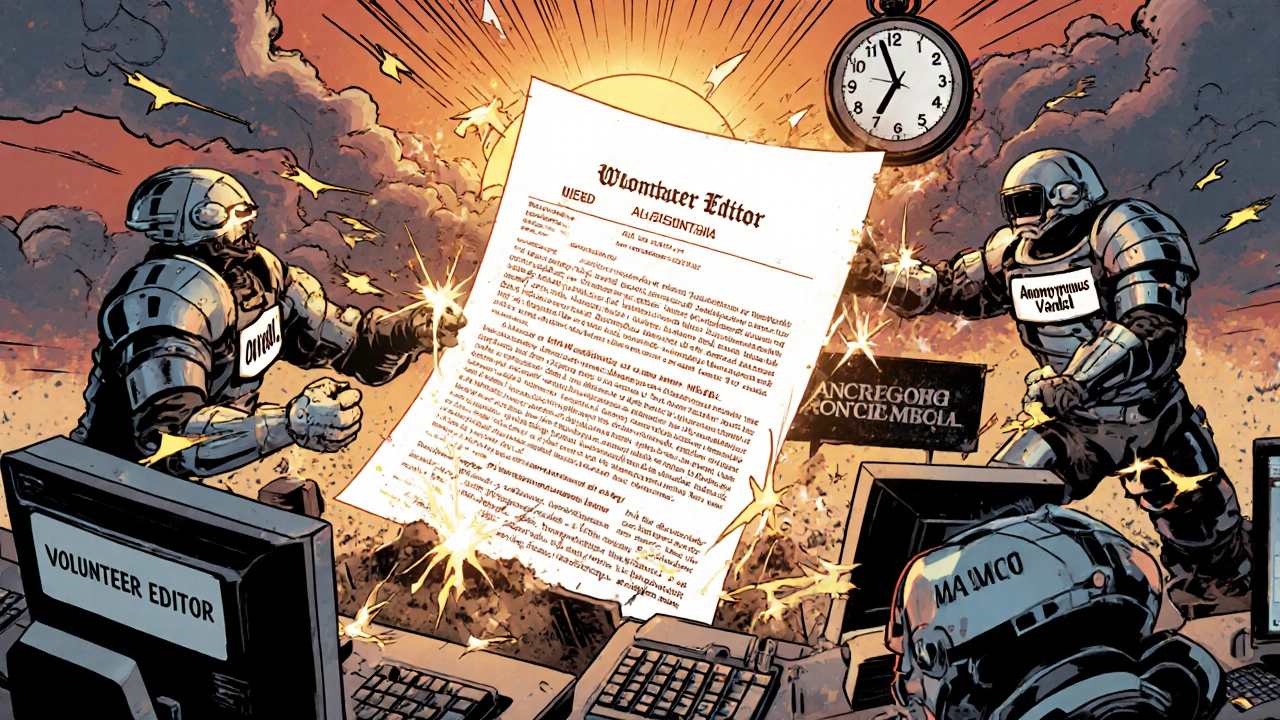

Wikipedia once had a page for a fictional character who didn’t exist

In 2005, a user created a page for John Seigenthaler-but not the real journalist. They made up a fake biography claiming he was involved in the assassinations of JFK and RFK. The article stayed live for four months. No one noticed. Not the editors, not the fact-checkers. It wasn’t until Seigenthaler himself found it and called out the error that it was removed. That incident led to Wikipedia’s biggest policy change: requiring registered accounts to create new articles. Before that, anyone could edit anonymously. After? The flood of nonsense slowed. But the story didn’t disappear. It became a case study in how trust works online-and why verification matters.

The oldest active Wikipedia edit is still visible

The very first edit to Wikipedia was made on January 15, 2001. It wasn’t about science, history, or technology. It was the word "Hello, World!"-a test. The user, Jimmy Wales, typed it into a blank page titled "Main Page." That edit still exists in the version history. You can click through and see it. The second edit? Someone changed it to "Hello, World! This is Wikipedia." The third? A typo fix. These aren’t just footnotes. They’re the birth of the internet’s most ambitious experiment in collective knowledge. And you can still see the first breath.

Wikipedia has a secret category for articles that are too weird to delete

It’s called Category:Articles that need to be deleted but are too interesting to delete. It’s not official. It’s not public. But it exists in the back-end of dozens of volunteer editors’ dashboards. It includes pages like How to make a banana sandwich (which has 17 citations from 1970s cookbooks), People who have won the Nobel Prize in Literature while being a professional clown (one person, and yes, it’s verified), and Objects that have been sent to space that are not spacecraft (including a LEGO minifigure, a copy of Don Quixote, and a pair of astronaut boots). These articles shouldn’t exist by Wikipedia’s rules. But they do. Because someone, somewhere, cared enough to document them. And that’s the whole point.

Wikipedia’s most controversial edit is still live

In 2018, someone changed the article on climate change to say "global warming is a hoax." It lasted 17 minutes before being reverted. But the edit was recorded. And it wasn’t the only one. That same day, over 1,200 edits were made to climate-related pages. Most were corrections. A few were vandalism. But one edit-just one-changed the word "scientific consensus" to "opinion." That edit was made by a user from a government IP address. It was caught. It was undone. But it was archived. And now, every time someone looks at the history of that page, they can see how easily truth can be bent. And how hard it is to keep it straight.

Wikipedia is the only major website that doesn’t sell your data

It’s not just ad-free. It doesn’t track you. Doesn’t collect your location. Doesn’t store your search history. Doesn’t sell your data to advertisers. It’s funded by donations. Over 200 million people use it every month. And it costs less than $100 million a year to run. That’s less than the salary of one NFL quarterback. The entire infrastructure-servers, bandwidth, staff-is maintained by a nonprofit that refuses to compromise its integrity. No one owns Wikipedia. No one profits from it. And yet, it’s the most trusted source of information on the planet.

Can anyone edit Wikipedia?

Yes, anyone can edit most articles. But since 2005, new users need to be registered to create new pages. Many high-traffic or sensitive pages are protected and can only be edited by experienced volunteers. Edits are reviewed by bots and human editors, and changes are logged publicly so you can always see who made what change and why.

Are Wikipedia facts always accurate?

Most are. Studies show Wikipedia’s accuracy rate is comparable to Encyclopedia Britannica for general topics. But because it’s open to editing, errors can slip through-especially on obscure or rapidly changing subjects. Always check the citations at the bottom of the page. Reliable sources like peer-reviewed journals, government reports, or major news outlets are preferred. If an article has no references, treat it with caution.

Why does Wikipedia have so many obscure articles?

Because someone cared enough to write them. Wikipedia doesn’t delete articles just because they seem unimportant. If a topic has reliable sources and meets notability guidelines, it stays-even if it’s about a single type of mushroom, a minor character from a 1980s cartoon, or a local bridge in Nebraska. The goal isn’t to be comprehensive in the traditional sense. It’s to be a record of what humans find worth documenting.

How does Wikipedia make money?

Wikipedia is run by the Wikimedia Foundation, a nonprofit that relies entirely on donations from users. It doesn’t run ads, doesn’t sell data, and doesn’t charge for access. In 2024, it raised over $160 million from 7 million individual donors. Most contributions are under $25. That’s how it stays free and independent.

Is Wikipedia biased?

It tries not to be. Wikipedia has strict policies on neutrality and requires citations from reliable sources. But bias can creep in-especially when certain topics attract more editors from one region or culture. For example, articles on European history are often more detailed than those on African or Indigenous histories. That’s why there are active efforts to fix these gaps through edit-a-thons and partnerships with universities and museums around the world.

What’s next for Wikipedia?

It’s not slowing down. In 2025, Wikipedia launched its first AI-assisted editing tool to help volunteers flag potential inaccuracies in real time. It doesn’t write articles-it suggests edits based on trusted sources. The goal? Reduce the time between an error and its correction. Meanwhile, mobile usage has surpassed desktop for the first time. More people are reading Wikipedia on their phones in rural villages, refugee camps, and classrooms without textbooks. The internet’s biggest encyclopedia is becoming its most essential tool for the unconnected.

Wikipedia isn’t perfect. But it’s the closest thing we have to a global memory-built not by institutions, but by ordinary people who believe knowledge should be free. The next time you open a page, look at the edit history. You’ll see names you don’t recognize. Dates from midnight. Comments like "fixed typo" or "added source." Those aren’t just edits. They’re quiet acts of faith in shared understanding.