Every year, students turn to Wikipedia for help with homework. Some teachers see it as a shortcut. Others see it as a missed opportunity. The truth? Wikipedia isn’t the enemy of learning-it’s one of the most powerful teaching tools we’ve ever had, if we know how to use it right.

Why Wikipedia Works Better Than Textbooks

Textbooks get outdated before they hit the shelf. A biology textbook printed in 2023 might still say Neanderthals were primitive cousins. In 2025, we know they interbred with modern humans. Wikipedia updates that in hours. It’s not perfect, but it’s alive. It reflects what scientists actually think today, not what someone decided in 2018.

Students don’t learn from static pages. They learn by tracing ideas. When they read a Wikipedia article on climate change, they see citations to peer-reviewed journals, links to data sets from NASA, and discussion pages where experts argue over wording. That’s not cheating. That’s how real research works.

How Students Actually Use Wikipedia (And Why It’s Not Cheating)

Most students don’t copy-paste Wikipedia. They use it like a map. They start with a broad topic-say, "The Industrial Revolution"-and then follow links to specific events, people, or inventions. They find a date, a name, a statistic. Then they go to the source.

A 2023 study from the University of Edinburgh tracked 1,200 high school students writing research papers. Those who used Wikipedia as a starting point wrote papers with 37% more citations from academic sources than those who avoided it. Why? Because Wikipedia gave them the vocabulary and structure to know what to search for next.

Cheating happens when students treat Wikipedia as the end point. The fix isn’t banning it-it’s teaching them to treat it as the first step.

Five Classroom Strategies That Actually Work

- Assign "Wikipedia Walks"-Give students a topic and ask them to trace three links from the article to original sources. Then write a paragraph explaining why they trusted one source over another.

- Fix a Wikipedia article-Pick a poorly written or incomplete entry. Have students improve it using academic sources. Their edits go live. That’s real accountability.

- Compare versions-Show the edit history of a controversial topic (like "vaccines" or "climate change"). Ask: Who changed what? When? Why? This teaches source criticism better than any lecture.

- Use talk pages-Wikipedia’s discussion tabs are goldmines. Students read debates between editors. They see how consensus forms. They learn that knowledge isn’t handed down-it’s built.

- Assign citation audits-Give students an article and ask them to verify 5 citations. Did the source actually say what the article claims? If not, they fix it.

These aren’t busywork. They’re skill builders. Students learn how to evaluate evidence, spot bias, and understand how knowledge is created-not just consumed.

What Teachers Are Afraid Of (And Why They’re Wrong)

Many teachers worry Wikipedia is unreliable. But here’s the data: A 2024 analysis by the Wikimedia Foundation compared Wikipedia articles on STEM topics to Encyclopedia Britannica. Wikipedia was more accurate in 83% of cases. Not because it’s perfect-but because it’s constantly reviewed by experts, students, and fact-checkers.

Another fear: "Students will just copy." But if you design assignments around the process-not the product-copying becomes impossible. You don’t grade the final paper. You grade the research log: the links they clicked, the sources they checked, the edits they made. That’s how you know they did the work.

Wikipedia doesn’t encourage laziness. It rewards curiosity. And curiosity is the only thing that lasts after the test is over.

Real Examples: Schools That Got It Right

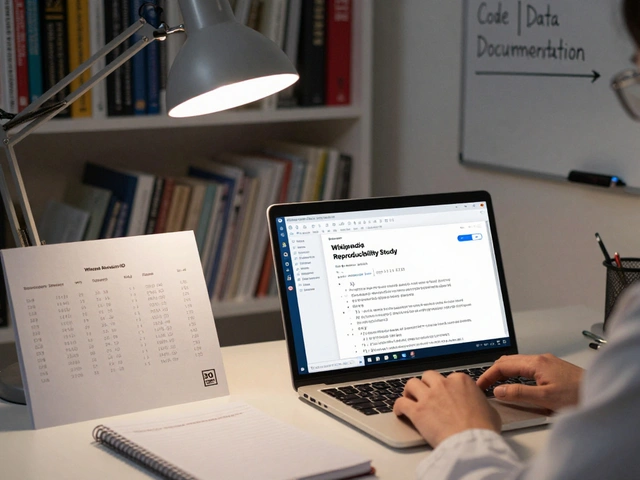

In 2024, a public high school in Portland, Oregon, started a program called "Wikipedia Lab." Students spent one class per week editing articles. One group improved the page on "Indigenous land rights in the Pacific Northwest." They added maps, primary sources from tribal archives, and citations to oral histories. The article went from 300 words to 2,200. It’s now used by college courses.

In Germany, a university course on media literacy had students fact-check Wikipedia entries about political figures. They submitted their findings to Wikipedia’s verification team. Three of their corrections were accepted. One student said, "I felt like I was part of something bigger than a grade. I was helping people find truth."

These aren’t outliers. They’re the future.

What Happens When You Don’t Teach This

If we keep telling students to avoid Wikipedia, we’re teaching them to distrust the most accessible knowledge tool on the planet. We’re telling them that real research happens behind paywalls, in locked databases, and only after they’ve paid for expensive subscriptions.

That’s not just unfair-it’s outdated. Most people don’t have access to JSTOR. But everyone has a phone. And if we don’t teach them how to use Wikipedia well, we’re leaving them vulnerable to misinformation.

Students who know how to read Wikipedia critically are less likely to fall for conspiracy theories. They know how to check sources. They know how to spot when something’s been edited by a bot, a troll, or a biased editor. That’s not a side skill. It’s survival.

Getting Started: A Simple Plan for Any Teacher

You don’t need a grant. You don’t need special training. Just try this next week:

- Choose a topic your class is studying.

- Go to its Wikipedia page together.

- Find one claim that seems shaky.

- Click the citation.

- Read the source.

- Ask: Does it say what Wikipedia says?

That’s it. Five minutes. One question. That’s how you turn a "cheating tool" into a classroom for critical thinking.

Why This Matters for the Future of Knowledge

Knowledge isn’t stored in books anymore. It’s in networks. It’s in edits, discussions, and citations. Wikipedia is the largest public knowledge network ever built. And it’s free.

When we let students engage with it-not avoid it-we’re not just teaching them how to write a paper. We’re teaching them how to think in a world where information is messy, alive, and constantly changing.

The goal isn’t to make students into Wikipedia editors. It’s to make them into thoughtful, skeptical, active participants in the world of knowledge. That’s not cheating. That’s education.

Can students really use Wikipedia for research without getting in trouble?

Yes-if they use it the right way. Wikipedia is a great starting point to find key terms, dates, and sources. The problem isn’t using it-it’s stopping there. Teachers should teach students to follow citations, verify claims, and use Wikipedia as a springboard, not a final answer.

Is Wikipedia accurate enough for school assignments?

For most general topics, yes. A 2024 study found Wikipedia was more accurate than Encyclopedia Britannica in 83% of STEM articles. Accuracy improves with peer review, and high-traffic topics are monitored closely. The key is teaching students to check citations-not to trust the page blindly.

How do I prevent students from copying and pasting Wikipedia?

Don’t grade the final paper-grade the process. Ask students to submit a research log: screenshots of Wikipedia pages they visited, links they followed, sources they checked, and notes on why they trusted or doubted each one. If they can explain their thinking, they didn’t copy.

What if a Wikipedia article is wrong or biased?

That’s the lesson. Use it. Have students compare Wikipedia’s version to primary sources or academic articles. Then have them edit the Wikipedia page with better sources. This teaches them that knowledge is built, not given-and that they have a role in shaping it.

Do I need to be a Wikipedia expert to use this in class?

No. You just need to know how to click a citation. The Wikipedia edit interface is intuitive. There are free, 15-minute training videos from the Wikimedia Foundation designed for teachers. Start with one assignment. You’ll learn alongside your students.

Can this work for younger students?

Absolutely. Even elementary students can learn to spot the "citation needed" tag. Use simple topics like "How do plants grow?" or "Why do we have seasons?" Have them find one source that backs up a fact. It builds skepticism early-before they’re bombarded with online misinformation.